-

全氟烷基化合物(PFASs)是指化合物分子中与碳原子链接的氢原子全部被氟原子所取代的一类新型有机化合物. PFASs分子中的C—F键十分稳定,因此在天然环境中往往具有较高的稳定性和持久性[1 − 2]. 全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)是一种典型的PFASs,在过去的几十年中,曾广泛应用于商业产品和工业过程中[2 − 3]. 由于PFOS的大量使用,已在全球不同地区的人类、鱼类、鸟类和哺乳动物中检测到其存在[4 − 6]. 研究表明,PFOS具有生物累积性,并且具有神经毒性、生殖发育毒性和内分泌干扰性等,对人体和其他生物造成了严重危害[7 − 11]. 2009年《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》第四次缔约方大会将PFOS及其盐类作为限制性化学品列入公约附件B[12]. 我国作为公约缔约方,也已于2014年禁止PFOS及其盐类除特定豁免和可接受用途外的生产、流通、使用和进出口. 可见,PFOS的调查和监控是一项全球性的重要环境课题,发展PFOS的快速筛查方法十分必要.

水体是PFOS在环境中重要的汇. 以我国为例,我国辽河流域、长江三角洲地区和珠江三角洲等地区均不同程度地受到了PFOS污染[13 − 16]. 目前水体PFOS的检测主要依赖于液相色谱-质谱技术[17],存在样品前处理复杂,设备价格高昂,操作繁琐、耗时等局限性,限制了其广泛应用. 荧光传感技术是一种灵敏度高、操作简便、可实时检测的化学物质分析技术,近年来已被成功用于快速筛查PFOS、全氟辛烷羧酸(PFOA)等多种PFASs[18 − 29],显示了优异的应用潜能. 目前可用于检测PFOS的荧光传感器以染料和碳量子点为主[18 − 23,27 − 29],不但种类有限、传感方式单一(以荧光猝灭为主),还存在PFOS响应时间长、检出限高等问题.

发光金属-有机骨架材料(LMOFs)是一类新型发光材料,具有理化性质稳定、比表面积高、结构多样可调等特点,近年来引起了荧光传感领域的广泛关注,在诸如挥发性有机化合物、生物分子、爆炸物、重金属等化学物质的传感中显示了出色的灵敏度、速度和选择性[30 − 31]. 本论文制备了锆基LMOFs(UiO-66-NH2),研究了其对PFOS的荧光传感性能,建立了水体PFOS的快速筛查方法,并在实际水体中验证了方法的可应用性.

-

PFOS(纯度98%)购自美国Sigma-Aldrich公司. 分析纯氯化锆(ZrCl4)、二甲基甲酰胺(DMF)、2-氨基对苯二甲酸(BDC-NH2)和十二水合磷酸钠(Na3PO4·12H2O)购自国药集团化学试剂有限公司. 纯盐酸(HCl)、乙酸(HAc)、乙酸钠(NaAc)、氢氧化钠(NaOH)、氯化钠(NaCl)、硫酸钠(Na2SO4)、硝酸钠(NaNO3)、碳酸氢钠(NaHCO3)、氯化钾(KCl)、六水合氯化镁(MgCl2·6H2O)、氯化钙(CaCl2)、六水合氯化铝(AlCl3·6H2O)、乙醇、氨水、甲醇均购自南京化学试剂有限公司,纯度为分析纯.

-

本研究合成UiO-66-NH2的步骤如下[32]:将1.00 g(4.32 mmol)ZrCl4溶于80 mL DMF,加入8 mL浓HCl后超声分散20 min. 向上述溶液中加入1.08 g(6 mmol)BDC-NH2和40 mL DMF,再次超声20 min至固体完全溶解. 将分散后的混合溶液转移至Pyrex瓶中,于80 ℃反应12 h. 待反应瓶自然冷却至室温后,过滤收集固体产物,并用DMF和乙醇分别洗涤产物3次,以去除残留溶剂. 最后,将所得固体置于真空烘箱中,90 ℃干燥24 h,得到UiO-66-NH2. 利用S-3400N型扫描电子显微镜(SEM,日本Hitachi公司)和D/max-RA型粉末X射线衍射仪(XRD,日本Rigaku公司)研究所制备UiO-66-NH2的形貌和晶体结构. 采用NEXUS870型傅里叶变换红外光谱仪(FTIR,美国NICOLET公司)对UiO-66-NH2进行官能团分析. 采用ASAP 2020型比表面积与孔径分布仪(美国Micrometrics公司)测量UiO-66-NH2的比表面积、孔容和孔径等孔道结构参数. 利用UV-

2700 型紫外-可见分光光谱仪(日本Shimadzu公司)和Aqualog型荧光光谱仪(日本HORIBA公司)研究UiO-66-NH2的光谱学性质. -

在10 mL聚丙烯离心管中加入适量UiO-66-NH2储备溶液(200 mg·L−1)、PFOS储备溶液(100 mg·L−1)和HAc-NaAc缓冲溶液(pH 3.0,10 mmol·L−1),使UiO-66-NH2浓度为2 mg·L−1、PFOS浓度为0—8 mg·L−1. 反应10 min后,利用Aqualog型荧光光谱仪采集上述溶液的二维荧光光谱(激发波长/Ex为330 nm),研究PFOS对UiO-66-NH2荧光发光的影响. 在共存离子影响实验中,采用荧光酶标仪(Infinite M200,瑞士TECEN公司)采集溶液在Ex为330 nm、发射波长(Em)为438 nm处的荧光强度,考察8种不同浓度(0.2 mg·L−1和2.0 mg·L−1)的常见离子(Cl−、SO42−、HCO3−、NO3−、PO43−、K+、Mg2+、Ca2+和Al3+)对UiO-66-NH2筛查PFOS的影响. 为考察UiO-66-NH2的可重复利用性,采用0.1%的氨水-甲醇溶液对使用后的UiO-66-NH2进行超声洗脱再生[33]. 在实际水体的加标回收实验中,PFOS的梯度加标浓度为1.0、2.0、5.0 mg·L−1.

-

图1(a)为论文所制备UiO-66-NH2的SEM图,可以看出该材料呈八面体结构,与文献报道的UiO-66-NH2形貌一致[34]. 图1(b)为UiO-66-NH2的XRD图谱,图谱中出现了3处明显的衍射峰,分别位于2θ = 7.32°、8.4°和25.66°处,与UiO-66-NH2的标准XRD图谱一致,证明合成的样品具有优良结晶度. 论文进一步利用氮气吸附-脱附等温线对UiO-66-NH2的比表面积和孔道结构进行分析,结果如图1(c)所示. UiO-66-NH2的孔道以微孔为主,含有少量介孔,孔径主要分布在0.5—2.1 nm. UiO-66-NH2的Brunauer-Emmett-Teller(BET)比表面积高达918.46 m2·g−1,与此前其它报道结果一致(如

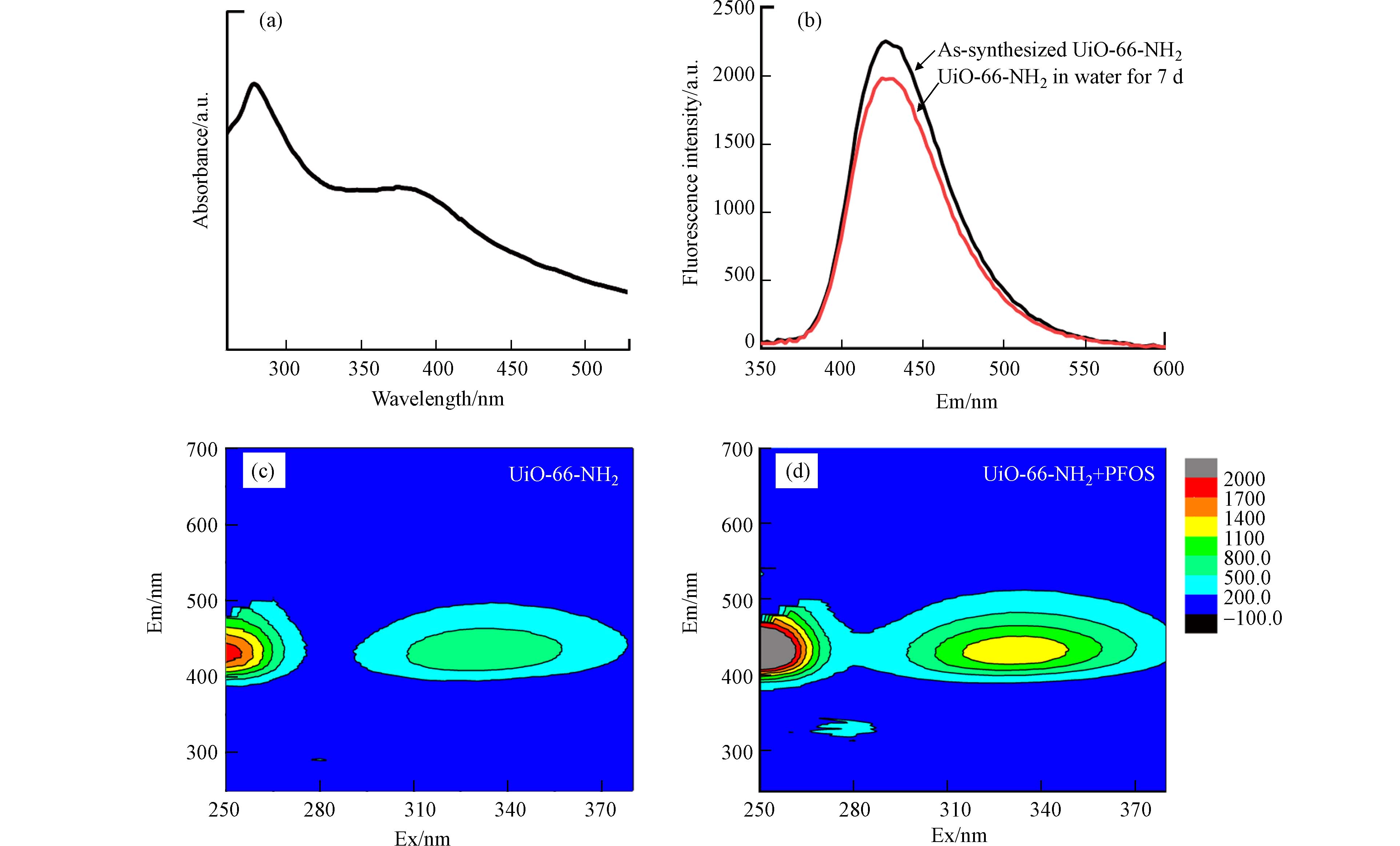

1052 m2·g−1[35]). UiO-66-NH2的FTIR如图1(d)所示,其中位于3342 cm−1和3452 cm−1处的双吸收峰分别来源于UiO-66-NH2胺基(—NH2)中N—H的不对称和对称拉伸振动;1250 cm−1处的峰为芳香胺的强C—N拉伸吸收;1574 cm−1和1386 cm−1处的峰为BDC-NH2配体中羧基(—COOH)的特征吸附峰,1496 cm−1处的吸收峰则对应于配体的芳香碳(—C=C—)振动;1658 cm−1处的吸收峰为羰基(—C=O)拉伸峰,产生于金属中心Zr与BDC-NH2羧基的脱羟基配位过程;位于低波数处的两个吸收峰(767 cm−1和663 cm–1)来源于UiO-66-NH2骨架的Zr—O键振动;FTIR光谱中出现的官能团类型和位置均与文献吻合[36 − 38]. 上述表征结果均证明,论文成功制备了UiO-66-NH2,且材料晶型良好.图2(a)为UiO-66-NH2的UV-vis吸收光谱图. UiO-66-NH2有两个主要吸收峰,分别对应于BDC-NH2配体的π-π*跃迁与Zr—O簇吸收之间的重叠(270 nm)和配体胺基中孤对电子的n-π*跃迁(380 nm)[37,39 − 40]. 三维荧光图谱显示,UiO-66-NH2受光激发后可进一步产生蓝色荧光,发光强度峰值分别位于Ex 250 nm/Em 438 nm和Ex 330 nm/Em 438 nm处(图2(c)). 加入PFOS(2.0 mg·L−1)后,UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射明显增强,表明其对PFOS具有荧光“开启”响应,可用于传感PFOS(图2(d)). UiO-66-NH2在两个荧光峰处的荧光增强程度相当,考虑250 nm已近仪器最低可采集Ex,故后续实验中选择Ex 330 nm以研究UiO-66-NH2对PFOS荧光传感性能. 图2(b)显示了放置一周后的UiO-66-NH2水溶液的二维荧光图谱(Ex为330 nm). 可以看出,UiO-66-NH2具有优秀的荧光稳定性和水稳定性,其水溶液在放置一周后无显著荧光发光衰减(Em处峰强降低约12%),表明UiO-66-NH2在水环境样品荧光筛查中具有良好的适用性.

-

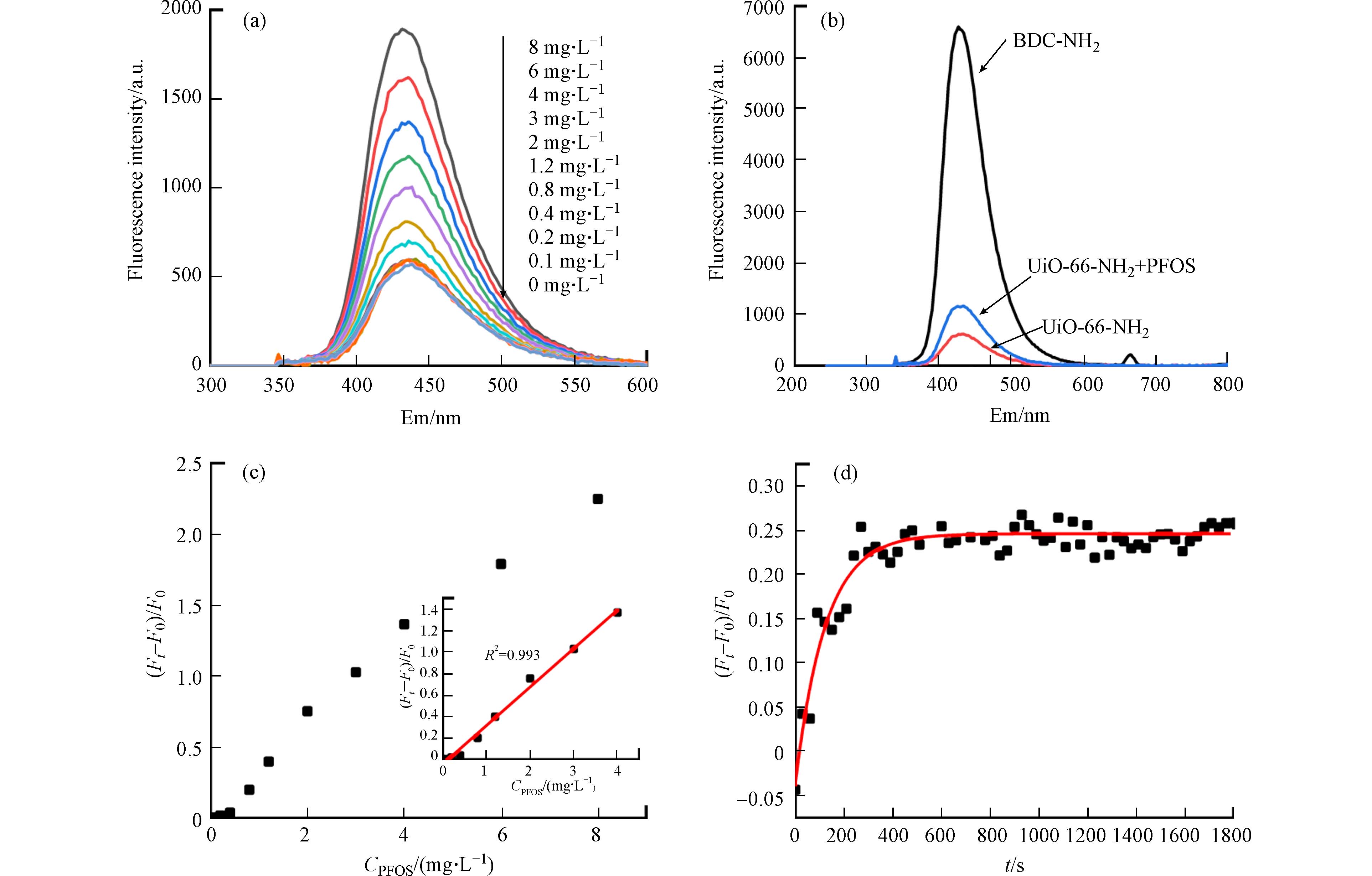

图3(a)展示了不同浓度PFOS存在下,UiO-66-NH2在Ex 330 nm处的二维荧光光谱图. 可以发现,UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度随着PFOS溶液浓度的增加而增加,2.0 mg·L−1的PFOS可使UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射(Em为438 nm)提高约2倍,而当PFOS增至8 mg·L−1时,UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强达到了3倍,这表明UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光“开启”响应可用于定量检测PFOS. 论文进而探究了UiO-66-NH2产生荧光“开启”响应的原因,对比了BDC-NH2单体、UiO-66-NH2与PFOS作用前后的二维荧光图谱. 如图3(b)所示,由于主要基于有机配体发光[41],UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射波长与BDC-NH2配体单体十分相近. 但UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度远低于同等浓度的BDC-NH2单体,仅为单体的9.56%,表明UiO-66-NH2中BDC-NH2与Zr的配体-金属电荷转移(LMCT)削弱了BDC-NH2的荧光发光(图4)[41]. 当PFOS存在时,UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度有所提高,但仍没有BDC-NH2单体高. 这是因为阴离子PFOS可与UiO-66-NH2中的金属Zr发生配位作用[42 − 43],会影响BDC-NH2-Zr间的LMCT,进而部分恢复BDC-NH2的荧光发射. Yang等[41]在此前的研究中指出,磷酸盐与BDC-NH2的竞争配位导致了UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强.

根据UiO-66-NH2在其荧光峰值处(Ex = 330 nm,Em = 438 nm)的荧光变化情况,可计算PFOS存在下UiO-66-NH2荧光的恢复程度:

其中,F0和Ft分别表示加入PFOS前后UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度. 如图3(c)所示,在0.1—4.0 mg·L−1(0.2—8.0 μmol·L−1)浓度范围内,PFOS浓度与UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强程度之间呈现出良好的线性关系(R2 = 0.993),表明UiO-66-NH2可用于定量筛查PFOS. 进一步根据下式计算UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的检出限(LOD)[44]:

其中,σ为F0的标准偏差. 结果显示,UiO-66-NH2检测PFOS的LOD为3.46 μg·L−1(即

0.0069 μmol·L−1),低于多数已报道PFOS荧光传感器的LOD值(详见表1),表明该方法具有良好的PFOS检测灵敏度.除检测灵敏度外,检测速度也是荧光传感的重要指标. 因此,论文研究了UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光传感动力学,结果如图3(d)所示. 加入PFOS溶液后UiO-66-NH2的荧光发光迅速增强,在400 s时发光强度即达到平衡,并保持稳定. UiO-66-NH2的这一PFOS响应速度也高于文献报道的多数荧光传感材料(表1). 其原因在于UiO-66-NH2具有高度规整、开放的孔道结构,有利于PFOS的扩散[41].

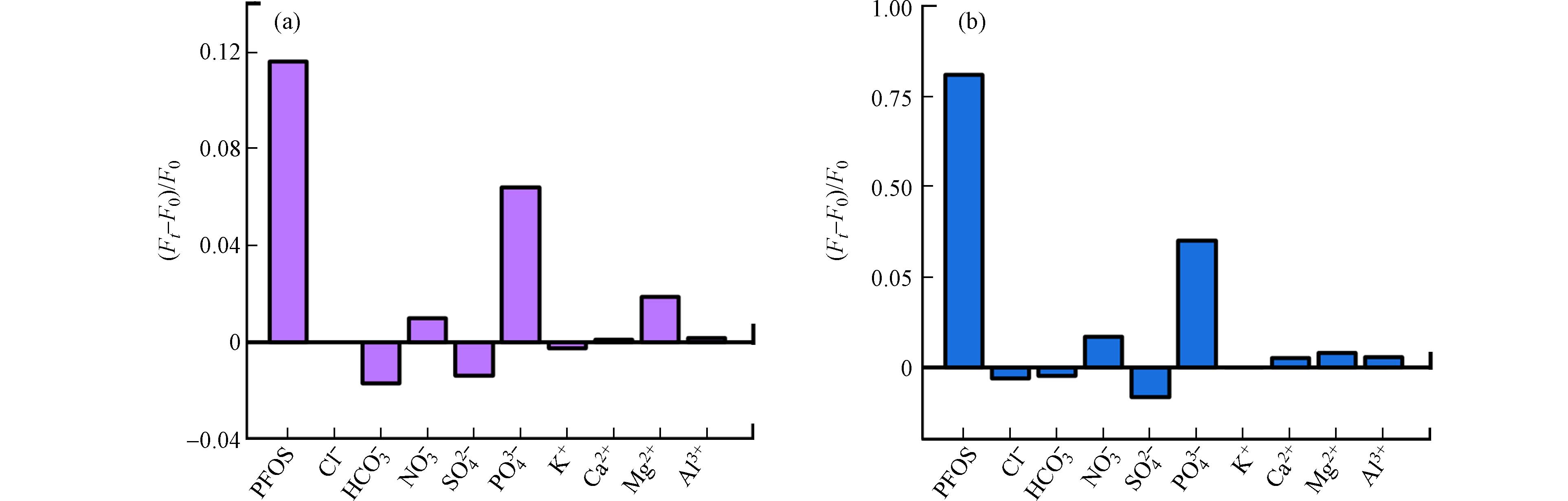

论文进一步考察了UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的选择性,研究了水体常见阴离子(Cl−、SO42−、HCO3−、NO3−和PO43−)和阳离子(K+、Mg2+、Ca2+、Al3+)对其PFOS传感性能的影响. 结果显示(图5),PFOS对UiO-66-NH2荧光的增强程度明显高于相同浓度的其它共存离子. 例如,2.0 mg·L−1的PFOS将UiO-66-NH2的荧光强度提升至初始值的1.81倍,但除PO43−外其它离子的提高在1.09倍以内,甚至呈微量猝灭效应. 由于具有较强的Zr配位能力,PO43−对UiO-66-NH2荧光的增强效率高于其它干扰离子(2.0 mg·L−1 PO43−的增强倍数为1.35),但增强程度仍明显低于PFOS. 可见,UiO-66-NH2可在其它常见离子共存情况下选择性检测PFOS. 这一方面是因为PFOS的磺酸基可与UiO-66-NH2的Zr金属节点发生较强的配位作用[42]. 另一方面,PFOS的全氟碳链具有高疏水性,其与UiO-66-NH2有机骨架间的疏水作用促进了PFOS在UiO-66-NH2中的富集,有利于PFOS与Zr节点配位.

研究了UiO-66-NH2传感器的循环使用性能,结果如图6所示. 在首次使用时,PFOS(2.0 mg·L−1)对UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强倍数为1.81倍;使用5次后,同浓度PFOS对UiO-66-NH2的增强倍数为1.76倍,为首次使用时的97%. 此外,UiO-66-NH2传感器6次循环测定的相对标准偏差仅为5.59%,说明其具有良好的可重复利用性.

-

为评估UiO-66-NH2在实际水体中的适用性,论文将其应用于检测自来水和地表水中的PFOS. 两类水样分别取自实验室水龙头和南京市九乡河,经0.22 μm滤膜过滤后直接用于分析. 结果显示,两类实际水样中的PFOS浓度均低于方法LOD值. 论文进一步开展了PFOS加标回收实验,发现在各加标浓度下,基于UiO-66-NH2的荧光法均具有良好的PFOS回收率(95.0%—106.5%),表明UiO-66-NH2可用于分析实际水体中的PFOS(表2).

-

本文以锆基荧光金属-有机骨架材料UiO-66-NH2为传感器,建立了水体全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)的快速荧光筛查方法. PFOS与UiO-66-NH2中金属锆的竞争配位可影响UiO-66-NH2骨架内的配体-金属电荷转移,使UiO-66-NH2荧光增强,产生荧光“开启”效应. 与文献报道的多数PFOS荧光检测法相比,基于UiO-66-NH2的方法对PFOS具有更低的检出限(

0.0069 μmol·L−1)和更快的响应平衡时间(400 s),且具有良好的筛查选择性和可重复利用性. 本研究结果可为水体PFOS的快速筛查提供技术支持,也有助于拓展荧光金属-有机骨架材料在荧光传感中的应用.

基于锆基荧光金属-有机骨架材料的水体全氟辛烷磺酸的快速筛查

Rapid fluorescent sensing of perfluorooctane sulfonate in water using a zirconium-based luminescent metal-organic framework

-

摘要: 本文以锆基荧光金属-有机骨架材料UiO-66-NH2为传感器,建立了水体全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)的快速荧光筛查方法. 利用扫描电子显微镜、X射线衍射、傅里叶变换红外光谱和荧光光谱等手段对UiO-66-NH2的结构和光学性质进行了分析,并且考察了UiO-66-NH2传感器对PFOS的传感灵敏度、速度和稳定性,及其在实际水体中的可应用性. 研究结果显示,UiO-66-NH2与其配体(2-氨基对苯二甲酸/BDC-NH2)具有相似的荧光性质,均可在光激发下产生稳定的蓝色荧光,但发光强度明显弱于BDC-NH2. 这是因为UiO-66-NH2中锆与BDC-NH2间的配体-金属电荷转移(LMCT)抑制了BDC-NH2的荧光发光. 而PFOS可与UiO-66-NH2锆金属节点发生作用,影响锆与BDC-NH2间的LMCT过程,进而恢复BDC-NH2的荧光,产生荧光“开启”响应. 在0.1—4.0 mg·L−1浓度范围内,PFOS浓度与UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强程度呈现良好线性正相关(R2 = 0.993). UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的检出限为3.46 μg·L−1(即

0.0069 μmol·L−1),低于文献中报道的多数PFOS荧光传感器. UiO-66-NH2还具有较快的PFOS响应速度,在与PFOS作用400 s之内即可达到荧光响应平衡. 此外,UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的传感过程基本不受水体常见阴、阳离子的影响,具有良好的可重复利用性,在实际水体筛查中也显示了高加标回收率(95.0%—106.5%),表明基于UiO-66-NH2的荧光法在水体PFOS的快速筛查中具有良好的应用潜能.-

关键词:

- 全氟辛烷磺酸 /

- 荧光传感 /

- 荧光金属-有机骨架材料 /

- 荧光开启.

Abstract: In this study, a fluorescent method was established for the rapid sensing of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in water using a zirconium-based luminescent metal-organic framework, UiO-66-NH2. The structural and optical spectral properties of the UiO-66-NH2 were characterized by combined techniques including scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and fluorescence spectroscopy. The sensing sensitivity, speed and stability of the UiO-66-NH2 sensor for PFOS, and its applicability in real water samples were investigated. The results showed that UiO-66-NH2 exhibited stable blue emission in water under light excitation, mainly originating from the 2-aminoterephthalic acid (BDC-NH2) ligand. The fluorescence emission of BDC-NH2 was weakened upon its integration into the framework of UiO-66-NH2 due to the ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT). The competitive coordination of PFOS with the zirconium node would interrupt the LMCT process and thus recover the emission of BDC-NH2, resulting in a fluorescent “turn-on” response. In the concentration range of 0.1—4.0 mg·L−1, the enhancement of UiO-66-NH2 fluorescence intensity (at excitation wavelength of 330 nm and emission wavelength of 438 nm) showed a good linear positive correlation with the concentration of PFOS (R2 = 0.993). The detection limit of PFOS by the fluorescence method based on UiO-66-NH2 was 3.46 μg·L−1 (i.e.,0.0069 μmol·L−1), lower than that of most reported PFOS fluorescence sensors. Moreover, UiO-66-NH2 afforded a rapid response speed towards PFOS, with a response equilibrium time within 400 s. The sensing performances of UiO-66-NH2 was scarcely affected by common interfering ions in water. The UiO-66-NH2-based sensing method also exhibited good reusability and high PFOS recoveries (95.0%—106.5%) in real water samples, suggesting its good applicability for PFOS screening in waters. -

全氟烷基化合物(PFASs)是指化合物分子中与碳原子链接的氢原子全部被氟原子所取代的一类新型有机化合物. PFASs分子中的C—F键十分稳定,因此在天然环境中往往具有较高的稳定性和持久性[1 − 2]. 全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)是一种典型的PFASs,在过去的几十年中,曾广泛应用于商业产品和工业过程中[2 − 3]. 由于PFOS的大量使用,已在全球不同地区的人类、鱼类、鸟类和哺乳动物中检测到其存在[4 − 6]. 研究表明,PFOS具有生物累积性,并且具有神经毒性、生殖发育毒性和内分泌干扰性等,对人体和其他生物造成了严重危害[7 − 11]. 2009年《关于持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》第四次缔约方大会将PFOS及其盐类作为限制性化学品列入公约附件B[12]. 我国作为公约缔约方,也已于2014年禁止PFOS及其盐类除特定豁免和可接受用途外的生产、流通、使用和进出口. 可见,PFOS的调查和监控是一项全球性的重要环境课题,发展PFOS的快速筛查方法十分必要.

水体是PFOS在环境中重要的汇. 以我国为例,我国辽河流域、长江三角洲地区和珠江三角洲等地区均不同程度地受到了PFOS污染[13 − 16]. 目前水体PFOS的检测主要依赖于液相色谱-质谱技术[17],存在样品前处理复杂,设备价格高昂,操作繁琐、耗时等局限性,限制了其广泛应用. 荧光传感技术是一种灵敏度高、操作简便、可实时检测的化学物质分析技术,近年来已被成功用于快速筛查PFOS、全氟辛烷羧酸(PFOA)等多种PFASs[18 − 29],显示了优异的应用潜能. 目前可用于检测PFOS的荧光传感器以染料和碳量子点为主[18 − 23,27 − 29],不但种类有限、传感方式单一(以荧光猝灭为主),还存在PFOS响应时间长、检出限高等问题.

发光金属-有机骨架材料(LMOFs)是一类新型发光材料,具有理化性质稳定、比表面积高、结构多样可调等特点,近年来引起了荧光传感领域的广泛关注,在诸如挥发性有机化合物、生物分子、爆炸物、重金属等化学物质的传感中显示了出色的灵敏度、速度和选择性[30 − 31]. 本论文制备了锆基LMOFs(UiO-66-NH2),研究了其对PFOS的荧光传感性能,建立了水体PFOS的快速筛查方法,并在实际水体中验证了方法的可应用性.

1. 实验部分(Experimental section)

1.1 化学试剂

PFOS(纯度98%)购自美国Sigma-Aldrich公司. 分析纯氯化锆(ZrCl4)、二甲基甲酰胺(DMF)、2-氨基对苯二甲酸(BDC-NH2)和十二水合磷酸钠(Na3PO4·12H2O)购自国药集团化学试剂有限公司. 纯盐酸(HCl)、乙酸(HAc)、乙酸钠(NaAc)、氢氧化钠(NaOH)、氯化钠(NaCl)、硫酸钠(Na2SO4)、硝酸钠(NaNO3)、碳酸氢钠(NaHCO3)、氯化钾(KCl)、六水合氯化镁(MgCl2·6H2O)、氯化钙(CaCl2)、六水合氯化铝(AlCl3·6H2O)、乙醇、氨水、甲醇均购自南京化学试剂有限公司,纯度为分析纯.

1.2 UiO-66-NH2的制备和表征方法

本研究合成UiO-66-NH2的步骤如下[32]:将1.00 g(4.32 mmol)ZrCl4溶于80 mL DMF,加入8 mL浓HCl后超声分散20 min. 向上述溶液中加入1.08 g(6 mmol)BDC-NH2和40 mL DMF,再次超声20 min至固体完全溶解. 将分散后的混合溶液转移至Pyrex瓶中,于80 ℃反应12 h. 待反应瓶自然冷却至室温后,过滤收集固体产物,并用DMF和乙醇分别洗涤产物3次,以去除残留溶剂. 最后,将所得固体置于真空烘箱中,90 ℃干燥24 h,得到UiO-66-NH2. 利用S-3400N型扫描电子显微镜(SEM,日本Hitachi公司)和D/max-RA型粉末X射线衍射仪(XRD,日本Rigaku公司)研究所制备UiO-66-NH2的形貌和晶体结构. 采用NEXUS870型傅里叶变换红外光谱仪(FTIR,美国NICOLET公司)对UiO-66-NH2进行官能团分析. 采用ASAP 2020型比表面积与孔径分布仪(美国Micrometrics公司)测量UiO-66-NH2的比表面积、孔容和孔径等孔道结构参数. 利用UV-

2700 型紫外-可见分光光谱仪(日本Shimadzu公司)和Aqualog型荧光光谱仪(日本HORIBA公司)研究UiO-66-NH2的光谱学性质.1.3 UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的传感性能研究方法

在10 mL聚丙烯离心管中加入适量UiO-66-NH2储备溶液(200 mg·L−1)、PFOS储备溶液(100 mg·L−1)和HAc-NaAc缓冲溶液(pH 3.0,10 mmol·L−1),使UiO-66-NH2浓度为2 mg·L−1、PFOS浓度为0—8 mg·L−1. 反应10 min后,利用Aqualog型荧光光谱仪采集上述溶液的二维荧光光谱(激发波长/Ex为330 nm),研究PFOS对UiO-66-NH2荧光发光的影响. 在共存离子影响实验中,采用荧光酶标仪(Infinite M200,瑞士TECEN公司)采集溶液在Ex为330 nm、发射波长(Em)为438 nm处的荧光强度,考察8种不同浓度(0.2 mg·L−1和2.0 mg·L−1)的常见离子(Cl−、SO42−、HCO3−、NO3−、PO43−、K+、Mg2+、Ca2+和Al3+)对UiO-66-NH2筛查PFOS的影响. 为考察UiO-66-NH2的可重复利用性,采用0.1%的氨水-甲醇溶液对使用后的UiO-66-NH2进行超声洗脱再生[33]. 在实际水体的加标回收实验中,PFOS的梯度加标浓度为1.0、2.0、5.0 mg·L−1.

2. 结果与讨论(Results and discussion)

2.1 UiO-66-NH2的表征结果

图1(a)为论文所制备UiO-66-NH2的SEM图,可以看出该材料呈八面体结构,与文献报道的UiO-66-NH2形貌一致[34]. 图1(b)为UiO-66-NH2的XRD图谱,图谱中出现了3处明显的衍射峰,分别位于2θ = 7.32°、8.4°和25.66°处,与UiO-66-NH2的标准XRD图谱一致,证明合成的样品具有优良结晶度. 论文进一步利用氮气吸附-脱附等温线对UiO-66-NH2的比表面积和孔道结构进行分析,结果如图1(c)所示. UiO-66-NH2的孔道以微孔为主,含有少量介孔,孔径主要分布在0.5—2.1 nm. UiO-66-NH2的Brunauer-Emmett-Teller(BET)比表面积高达918.46 m2·g−1,与此前其它报道结果一致(如

1052 m2·g−1[35]). UiO-66-NH2的FTIR如图1(d)所示,其中位于3342 cm−1和3452 cm−1处的双吸收峰分别来源于UiO-66-NH2胺基(—NH2)中N—H的不对称和对称拉伸振动;1250 cm−1处的峰为芳香胺的强C—N拉伸吸收;1574 cm−1和1386 cm−1处的峰为BDC-NH2配体中羧基(—COOH)的特征吸附峰,1496 cm−1处的吸收峰则对应于配体的芳香碳(—C=C—)振动;1658 cm−1处的吸收峰为羰基(—C=O)拉伸峰,产生于金属中心Zr与BDC-NH2羧基的脱羟基配位过程;位于低波数处的两个吸收峰(767 cm−1和663 cm–1)来源于UiO-66-NH2骨架的Zr—O键振动;FTIR光谱中出现的官能团类型和位置均与文献吻合[36 − 38]. 上述表征结果均证明,论文成功制备了UiO-66-NH2,且材料晶型良好.图2(a)为UiO-66-NH2的UV-vis吸收光谱图. UiO-66-NH2有两个主要吸收峰,分别对应于BDC-NH2配体的π-π*跃迁与Zr—O簇吸收之间的重叠(270 nm)和配体胺基中孤对电子的n-π*跃迁(380 nm)[37,39 − 40]. 三维荧光图谱显示,UiO-66-NH2受光激发后可进一步产生蓝色荧光,发光强度峰值分别位于Ex 250 nm/Em 438 nm和Ex 330 nm/Em 438 nm处(图2(c)). 加入PFOS(2.0 mg·L−1)后,UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射明显增强,表明其对PFOS具有荧光“开启”响应,可用于传感PFOS(图2(d)). UiO-66-NH2在两个荧光峰处的荧光增强程度相当,考虑250 nm已近仪器最低可采集Ex,故后续实验中选择Ex 330 nm以研究UiO-66-NH2对PFOS荧光传感性能. 图2(b)显示了放置一周后的UiO-66-NH2水溶液的二维荧光图谱(Ex为330 nm). 可以看出,UiO-66-NH2具有优秀的荧光稳定性和水稳定性,其水溶液在放置一周后无显著荧光发光衰减(Em处峰强降低约12%),表明UiO-66-NH2在水环境样品荧光筛查中具有良好的适用性.

2.2 UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光传感性能

图3(a)展示了不同浓度PFOS存在下,UiO-66-NH2在Ex 330 nm处的二维荧光光谱图. 可以发现,UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度随着PFOS溶液浓度的增加而增加,2.0 mg·L−1的PFOS可使UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射(Em为438 nm)提高约2倍,而当PFOS增至8 mg·L−1时,UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强达到了3倍,这表明UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光“开启”响应可用于定量检测PFOS. 论文进而探究了UiO-66-NH2产生荧光“开启”响应的原因,对比了BDC-NH2单体、UiO-66-NH2与PFOS作用前后的二维荧光图谱. 如图3(b)所示,由于主要基于有机配体发光[41],UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射波长与BDC-NH2配体单体十分相近. 但UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度远低于同等浓度的BDC-NH2单体,仅为单体的9.56%,表明UiO-66-NH2中BDC-NH2与Zr的配体-金属电荷转移(LMCT)削弱了BDC-NH2的荧光发光(图4)[41]. 当PFOS存在时,UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度有所提高,但仍没有BDC-NH2单体高. 这是因为阴离子PFOS可与UiO-66-NH2中的金属Zr发生配位作用[42 − 43],会影响BDC-NH2-Zr间的LMCT,进而部分恢复BDC-NH2的荧光发射. Yang等[41]在此前的研究中指出,磷酸盐与BDC-NH2的竞争配位导致了UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强.

图 3 (a)PFOS存在下UiO-66-NH2的二维荧光光谱(Ex= 330 nm);(b)BDC-NH2单体的二维荧光光谱(Ex= 330 nm);(c)PFOS浓度与UiO-66-NH2荧光增强的相关关系;(d)UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光响应动力学Figure 3. Fluorescence spectra at Ex 330 nm of (a) UiO-66-NH2 solution upon the addition of PFOS and (b) BDC-NH2 linker; (c) relationship between fluorescence enhancement of UiO-66-NH2 and PFOS concentration; (d) fluorescence response of UiO-66-NH2 to PFOS as function of interaction time

图 3 (a)PFOS存在下UiO-66-NH2的二维荧光光谱(Ex= 330 nm);(b)BDC-NH2单体的二维荧光光谱(Ex= 330 nm);(c)PFOS浓度与UiO-66-NH2荧光增强的相关关系;(d)UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光响应动力学Figure 3. Fluorescence spectra at Ex 330 nm of (a) UiO-66-NH2 solution upon the addition of PFOS and (b) BDC-NH2 linker; (c) relationship between fluorescence enhancement of UiO-66-NH2 and PFOS concentration; (d) fluorescence response of UiO-66-NH2 to PFOS as function of interaction time根据UiO-66-NH2在其荧光峰值处(Ex = 330 nm,Em = 438 nm)的荧光变化情况,可计算PFOS存在下UiO-66-NH2荧光的恢复程度:

荧光恢复率=Ft−F0F0 (1) 其中,F0和Ft分别表示加入PFOS前后UiO-66-NH2的荧光发射强度. 如图3(c)所示,在0.1—4.0 mg·L−1(0.2—8.0 μmol·L−1)浓度范围内,PFOS浓度与UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强程度之间呈现出良好的线性关系(R2 = 0.993),表明UiO-66-NH2可用于定量筛查PFOS. 进一步根据下式计算UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的检出限(LOD)[44]:

LOD=3σ斜率 (2) 其中,σ为F0的标准偏差. 结果显示,UiO-66-NH2检测PFOS的LOD为3.46 μg·L−1(即

0.0069 μmol·L−1),低于多数已报道PFOS荧光传感器的LOD值(详见表1),表明该方法具有良好的PFOS检测灵敏度.表 1 文献已报道PFOS荧光传感器的检测性能Table 1. Analytical performances of reported fluorescence methods for PFOS sensing探针Sensor 检出限/(μmol·L−1)LOD 线性范围/(μmol·L−1)Linear Range 响应时间/sResponse time 文献References 黄色曙红/聚乙烯亚胺 0.0150 0—2.0 600 [18] 赤藓红B/十六烷基三甲基溴化铵 0.0128 0.05—10 600 [19] 赤藓红B/硅氧烷 2.7000 0—40 150 [20] 耐尔蓝A 0.0032 0.05—4.0 1200 [21] 丙烯酰丹/肝型脂肪酸结合蛋白 0.6898 0.1—10 300 [22] 异硫氰酸荧光素/分子印迹材料/SiO2纳米颗粒 0.0111 0.01—0.09 300 [23] Guanidinocalix[5]arenes超分子 0.0214 0—0.70 N.A.a [24] BowtieCyclophane超分子大环 0.0473 0—0.60 30 [25] 苝二酰亚胺衍生物 0.0280 0.1—1.5 600 [26] 碳量子点 0.0183 0—12.0 1200 [27] 碳量子点/盐酸小檗碱 0.0217 0.22—50 600 [28] 氮掺杂碳量子点/溴化乙锭 0.0278 0—2.0 1200 [29] UiO-66-NH2 0.0069 0.1—8.0 400 本论文 注:a “N.A.” 文中未提及. a “N.A.” Not available. 除检测灵敏度外,检测速度也是荧光传感的重要指标. 因此,论文研究了UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光传感动力学,结果如图3(d)所示. 加入PFOS溶液后UiO-66-NH2的荧光发光迅速增强,在400 s时发光强度即达到平衡,并保持稳定. UiO-66-NH2的这一PFOS响应速度也高于文献报道的多数荧光传感材料(表1). 其原因在于UiO-66-NH2具有高度规整、开放的孔道结构,有利于PFOS的扩散[41].

论文进一步考察了UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的选择性,研究了水体常见阴离子(Cl−、SO42−、HCO3−、NO3−和PO43−)和阳离子(K+、Mg2+、Ca2+、Al3+)对其PFOS传感性能的影响. 结果显示(图5),PFOS对UiO-66-NH2荧光的增强程度明显高于相同浓度的其它共存离子. 例如,2.0 mg·L−1的PFOS将UiO-66-NH2的荧光强度提升至初始值的1.81倍,但除PO43−外其它离子的提高在1.09倍以内,甚至呈微量猝灭效应. 由于具有较强的Zr配位能力,PO43−对UiO-66-NH2荧光的增强效率高于其它干扰离子(2.0 mg·L−1 PO43−的增强倍数为1.35),但增强程度仍明显低于PFOS. 可见,UiO-66-NH2可在其它常见离子共存情况下选择性检测PFOS. 这一方面是因为PFOS的磺酸基可与UiO-66-NH2的Zr金属节点发生较强的配位作用[42]. 另一方面,PFOS的全氟碳链具有高疏水性,其与UiO-66-NH2有机骨架间的疏水作用促进了PFOS在UiO-66-NH2中的富集,有利于PFOS与Zr节点配位.

研究了UiO-66-NH2传感器的循环使用性能,结果如图6所示. 在首次使用时,PFOS(2.0 mg·L−1)对UiO-66-NH2的荧光增强倍数为1.81倍;使用5次后,同浓度PFOS对UiO-66-NH2的增强倍数为1.76倍,为首次使用时的97%. 此外,UiO-66-NH2传感器6次循环测定的相对标准偏差仅为5.59%,说明其具有良好的可重复利用性.

2.3 UiO-66-NH2对实际水体中PFOS的检测性能

为评估UiO-66-NH2在实际水体中的适用性,论文将其应用于检测自来水和地表水中的PFOS. 两类水样分别取自实验室水龙头和南京市九乡河,经0.22 μm滤膜过滤后直接用于分析. 结果显示,两类实际水样中的PFOS浓度均低于方法LOD值. 论文进一步开展了PFOS加标回收实验,发现在各加标浓度下,基于UiO-66-NH2的荧光法均具有良好的PFOS回收率(95.0%—106.5%),表明UiO-66-NH2可用于分析实际水体中的PFOS(表2).

表 2 UiO-66-NH2对实际水样中PFOS的检测结果Table 2. Analytical results for the determination of PFOS by UiO-66-NH2 in real water samples加标浓度/(mg·L−1)Spiked concentration 自来水样 九乡河水样 检出浓度/(mg·L−1)Detected concentration 回收率/%Recovery 检出浓度/(mg·L−1)Detected concentration 回收率/%Recovery 1.0 0.98 98.1 1.04 104.3 2.0 1.88 96.0 2.13 106.5 4.0 4.10 102.6 3.82 95.5 3. 结论(Conclusion)

本文以锆基荧光金属-有机骨架材料UiO-66-NH2为传感器,建立了水体全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)的快速荧光筛查方法. PFOS与UiO-66-NH2中金属锆的竞争配位可影响UiO-66-NH2骨架内的配体-金属电荷转移,使UiO-66-NH2荧光增强,产生荧光“开启”效应. 与文献报道的多数PFOS荧光检测法相比,基于UiO-66-NH2的方法对PFOS具有更低的检出限(

0.0069 μmol·L−1)和更快的响应平衡时间(400 s),且具有良好的筛查选择性和可重复利用性. 本研究结果可为水体PFOS的快速筛查提供技术支持,也有助于拓展荧光金属-有机骨架材料在荧光传感中的应用. -

图 3 (a)PFOS存在下UiO-66-NH2的二维荧光光谱(Ex= 330 nm);(b)BDC-NH2单体的二维荧光光谱(Ex= 330 nm);(c)PFOS浓度与UiO-66-NH2荧光增强的相关关系;(d)UiO-66-NH2对PFOS的荧光响应动力学

Figure 3. Fluorescence spectra at Ex 330 nm of (a) UiO-66-NH2 solution upon the addition of PFOS and (b) BDC-NH2 linker; (c) relationship between fluorescence enhancement of UiO-66-NH2 and PFOS concentration; (d) fluorescence response of UiO-66-NH2 to PFOS as function of interaction time

表 1 文献已报道PFOS荧光传感器的检测性能

Table 1. Analytical performances of reported fluorescence methods for PFOS sensing

探针Sensor 检出限/(μmol·L−1)LOD 线性范围/(μmol·L−1)Linear Range 响应时间/sResponse time 文献References 黄色曙红/聚乙烯亚胺 0.0150 0—2.0 600 [18] 赤藓红B/十六烷基三甲基溴化铵 0.0128 0.05—10 600 [19] 赤藓红B/硅氧烷 2.7000 0—40 150 [20] 耐尔蓝A 0.0032 0.05—4.0 1200 [21] 丙烯酰丹/肝型脂肪酸结合蛋白 0.6898 0.1—10 300 [22] 异硫氰酸荧光素/分子印迹材料/SiO2纳米颗粒 0.0111 0.01—0.09 300 [23] Guanidinocalix[5]arenes超分子 0.0214 0—0.70 N.A.a [24] BowtieCyclophane超分子大环 0.0473 0—0.60 30 [25] 苝二酰亚胺衍生物 0.0280 0.1—1.5 600 [26] 碳量子点 0.0183 0—12.0 1200 [27] 碳量子点/盐酸小檗碱 0.0217 0.22—50 600 [28] 氮掺杂碳量子点/溴化乙锭 0.0278 0—2.0 1200 [29] UiO-66-NH2 0.0069 0.1—8.0 400 本论文 注:a “N.A.” 文中未提及. a “N.A.” Not available. 表 2 UiO-66-NH2对实际水样中PFOS的检测结果

Table 2. Analytical results for the determination of PFOS by UiO-66-NH2 in real water samples

加标浓度/(mg·L−1)Spiked concentration 自来水样 九乡河水样 检出浓度/(mg·L−1)Detected concentration 回收率/%Recovery 检出浓度/(mg·L−1)Detected concentration 回收率/%Recovery 1.0 0.98 98.1 1.04 104.3 2.0 1.88 96.0 2.13 106.5 4.0 4.10 102.6 3.82 95.5 -

[1] LINDSTROM A B, STRYNAR M J, LIBELO E L. Polyfluorinated compounds: Past, present, and future[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(19): 7954-7961. [2] GIESY J P, KANNAN K. Perfluorochemical surfactants in the environment[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2002, 36(7): 146-152. [3] HIGGINS C P, FIELD J A. Our stainfree future?A virtual issue on poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(11): 5859-5860. [4] KANNAN K, CORSOLINI S, FALANDYSZ J, et al. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorinated hydrocarbons in marine mammals, fishes, and birds from coasts of the Baltic and the Mediterranean Seas[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2002, 36(15): 3210-3216. [5] GIESY J P, KANNAN K. Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2001, 35(7): 1339-1342. [6] YEUNG L W Y, MIYAKE Y, TANIYASU S, et al. Perfluorinated compounds and total and extractable organic fluorine in human blood samples from China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(21): 8140-8145. [7] SEACAT A M, THOMFORD P J, HANSEN K J, et al. Sub-chronic dietary toxicity of potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate in rats[J]. Toxicology, 2003, 183(1/2/3): 117-131. [8] FUENTES S, COLOMINA M T, VICENS P, et al. Influence of maternal restraint stress on the long-lasting effects induced by prenatal exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) in mice[J]. Toxicology Letters, 2007, 171(3): 162-170. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.05.006 [9] QIN X D, QIAN Z M, VAUGHN M G, et al. Positive associations of serum perfluoroalkyl substances with uric acid and hyperuricemia in children from Taiwan[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 212: 519-524. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.02.050 [10] 刘嘉烈, 石运刚, 唐娜, 等. 重庆长江流域鲫鱼和沉积物中17种全氟化合物污染特征[J]. 环境化学, 2020, 39(12): 3450-3461. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020061702 LIU J L, SHI Y G, TANG N, et al. Pollution characteristics of seventeen per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in fish and sediments of Yangtze River Basin in Chongqing City[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2020, 39(12): 3450-3461 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2020061702

[11] 杨琳, 李敬光, 石瑀, 等. 北京母亲静脉血与脐带血中全氟化合物前体物质含量分析[J]. 环境化学, 2015, 34(5): 869-874. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2015.05.2015012602 YANG L, LI J G, SHI Y, et al. Analysis of perfluoroalkyl acid precursors in paired maternal and cord serum in Beijing[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2015, 34(5): 869-874 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2015.05.2015012602

[12] WANG T, WANG Y W, LIAO C Y, et al. Perspectives on the inclusion of perfluorooctane sulfonate into the Stockholm convention on persistent organic pollutants[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2009, 43(14): 5171-5175. [13] CHEN X W, ZHU L Y, PAN X Y, et al. Isomeric specific partitioning behaviors of perfluoroalkyl substances in water dissolved phase, suspended particulate matters and sediments in Liao River Basin and Taihu Lake, China[J]. Water Research, 2015, 80: 235-244. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.04.032 [14] SO M K, MIYAKE Y, YEUNG W Y, et al. Perfluorinated compounds in the Pearl River and Yangtze River of China[J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 68(11): 2085-2095. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.02.008 [15] YU L, LIU X D, HUA Z L, et al. Spatial and temporal trends of perfluoroalkyl acids in water bodies: A case study in Taihu Lake, China (2009-2021)[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2022, 293: 118575. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118575 [16] YU N Y, SHI W, ZHANG B B, et al. Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl acids including perfluorooctane sulfonate isomers in Huai River Basin and Taihu Lake in Jiangsu Province, China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(2): 710-717. [17] YAMASHITA N, KANNAN K, TANIYASU S, et al. Analysis of perfluorinated acids at parts-per-quadrillion levels in seawater using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2004, 38(21): 5522-5528. [18] LIANG J M, DENG X Y, TAN K J. An eosin Y-based “turn-on” fluorescent sensor for detection of perfluorooctane sulfonate[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A:Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2015, 150: 772-777. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.05.069 [19] CHENG Z, DU L L, ZHU P P, et al. An erythrosin B-based “turn on” fluorescent sensor for detecting perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid in environmental water samples[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A:Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2018, 201: 281-287. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.05.013 [20] GOU Z M, WANG A J, ZHANG X M, et al. Multi-head cationic siloxane based “turn on” fluorescent system for selective detection of perfluorooctanoic sulfonate (PFOS)[J]. Sensors and Actuators B:Chemical, 2022, 367: 132017. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2022.132017 [21] CHEN Q, CHENG Z, DU L L, et al. A sensitive three-signal assay for the determination of PFOS based on the interaction with Nile blue A[J]. Analytical Methods, 2018, 10(25): 3052-3058. doi: 10.1039/C8AY00938D [22] MANN M M, TANG J D, BERGER B W. Engineering human liver fatty acid binding protein for detection of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2022, 119(2): 513-522. doi: 10.1002/bit.27981 [23] FENG H, WANG N Y, TRAN T T, et al. Surface molecular imprinting on dye-(NH2)-SiO2 NPs for specific recognition and direct fluorescent quantification of perfluorooctane sulfonate[J]. Sensors and Actuators B:Chemical, 2014, 195: 266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.01.036 [24] ZHENG Z, YU H J, GENG W C, et al. Guanidinocalix[5]arene for sensitive fluorescence detection and magnetic removal of perfluorinated pollutants[J]. Nature Communications, 2019, 10: 5762. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13775-1 [25] LEI S N, CONG H. Fluorescence detection of perfluorooctane sulfonate in water employing a tetraphenylethylene-derived dual macrocycle BowtieCyclophane[J]. Chinese Chemical Letters, 2022, 33(3): 1493-1496. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.068 [26] ZHANG Q J, LIAO M Y, XIAO K R, et al. A water-soluble fluorescence probe based on perylene diimide for rapid and selective detection of perfluorooctane sulfonate in 100% aqueous media[J]. Sensors and Actuators B:Chemical, 2022, 350: 130851. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2021.130851 [27] CHEN Q, ZHU P P, XIONG J, et al. A sensitive and selective triple-channel optical assay based on red-emissive carbon dots for the determination of PFOS[J]. Microchemical Journal, 2019, 145: 388-396. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2018.11.003 [28] CHENG Z, DONG H C, LIANG J M, et al. Highly selective fluorescent visual detection of perfluorooctane sulfonate via blue fluorescent carbon dots and berberine chloride hydrate[J]. Spectrochimica Acta Part A:Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2019, 207: 262-269. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.09.028 [29] CHEN Q, ZHU P P, XIONG J, et al. A new dual-recognition strategy for hybrid ratiometric and ratiometric sensing perfluorooctane sulfonic acid based on high fluorescent carbon dots with ethidium bromide[J]. Spectrochimica Acta. Part A, Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 2020, 224: 117362. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117362 [30] LUSTIG W P, MUKHERJEE S, RUDD N D, et al. Metal-organic frameworks: Functional luminescent and photonic materials for sensing applications[J]. Chemical Society Reviews, 2017, 46(11): 3242-3285. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00930A [31] RASHEED T, NABEEL F. Luminescent metal-organic frameworks as potential sensory materials for various environmental toxic agents[J]. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2019, 401: 213065. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213065 [32] SCHAATE A, ROY P, GODT A, et al. Modulated synthesis of Zr-based metal-organic frameworks: From nano to single crystals[J]. Chemistry, 2011, 17(24): 6643-6651. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003211 [33] TAN W, ZHU L, TIAN L F, et al. Preparation of cationic hierarchical porous covalent organic frameworks for rapid and effective enrichment of perfluorinated substances in dairy products[J]. Journal of Chromatography. A, 2022, 1675: 463188. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2022.463188 [34] CHUN J, KANG S, PARK N, et al. Metal-organic framework@microporous organic network: Hydrophobic adsorbents with a crystalline inner porosity[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2014, 136(19): 6786-6789. doi: 10.1021/ja500362w [35] LI Y, LIU J T, ZHANG K H, et al. UiO-66-NH2@PMAA: A hybrid polymer-MOFs architecture for pectinase immobilization[J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2018, 57(2): 559-567. [36] LV G R, LIU J M, XIONG Z H, et al. Selectivity adsorptive mechanism of different nitrophenols on UIO-66 and UIO-66-NH2 in aqueous solution[J]. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 2016, 61(11): 3868-3876. [37] ZHU H L, HUANG J P, ZHOU Q Y, et al. Enhanced luminescence of NH2-UiO-66 for selectively sensing fluoride anion in water medium[J]. Journal of Luminescence, 2019, 208: 67-74. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.12.007 [38] KANDIAH M, NILSEN M H, USSEGLIO S, et al. Synthesis and stability of tagged UiO-66 Zr-MOFs[J]. Chemistry of Materials, 2010, 22(24): 6632-6640. doi: 10.1021/cm102601v [39] PEÑAS-GARZÓN M, SAMPAIO M J, WANG Y L, et al. Solar photocatalytic degradation of parabens using UiO-66-NH2[J]. Separation and Purification Technology, 2022, 286: 120467. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120467 [40] JIA P, YANG K R, HOU J J, et al. Ingenious dual-emitting Ru@UiO-66-NH2 composite as ratiometric fluorescence sensor for detection of mercury in aqueous[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 408: 124469. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124469 [41] YANG J, DAI Y, ZHU X Y, et al. Metal-organic frameworks with inherent recognition sites for selective phosphate sensing through their coordination-induced fluorescence enhancement effect[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2015, 3(14): 7445-7452. doi: 10.1039/C5TA00077G [42] CLARK C A, HECK K N, POWELL C D, et al. Highly defective UiO-66 materials for the adsorptive removal of perfluorooctanesulfonate[J]. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2019, 7(7): 6619-6628. [43] LI R, ALOMARI S, STANTON R, et al. Efficient removal of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from water with zirconium-based metal–organic frameworks[J]. Chemistry of Materials, 2021, 33(9): 3276-3285. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c00324 [44] CHEN Y Z, JIANG H L. Porphyrinic metal–organic framework catalyzed heck-reaction: Fluorescence “turn-on” sensing of Cu(II) ion[J]. Chemistry of Materials, 2016, 28(18): 6698-6704. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03030 期刊类型引用(1)

1. 刘登平,陆恬,杨星琦,张冬辉,夏瑜. 金属-有机框架传感器检测水环境中全氟和多氟化合物研究进展. 食品安全导刊. 2025(03): 159-164 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

-

下载:

下载: