-

邻苯二甲酸酯(phthalic acid esters,PAEs)是邻苯二甲酸形成酯的统称,广泛用于聚氯乙烯材料、玩具、食用包装材料、头发喷雾剂、医用血管和胶袋等数百种产品中[1]. PAEs的毒性包括生殖毒性[2]、内分泌毒性[3]以及潜在遗传毒性[4]等. 现已在大气灰尘[5]、土壤[6]、水[7]和人体体液[8]中广泛测得PAEs. 作为一种环境内分泌干扰物,其半衰期很短,大约在24 h到48 h之间[9]. PAEs在人体内的检测浓度存在差异,这可能受到半衰期的影响. 同时,人类日常接触的物品中PAEs含量不同也会对其产生影响[10]. 基于PAEs的毒性作用,目前每个国家都已制定有关邻苯二甲酸酯使用的规定. 欧盟、世界卫生组织、美国、日本和中国均先后将邻苯二甲酸酯类污染物列入“优先控制污染名单”[11]. 其中,美国禁止销售邻苯二甲酸酯浓度超过0.1%的玩具[12];阿根廷、巴西和日本等国家规定玩具中DEHP、DBP等PAEs最大含量不超过0.1%[10];韩国国家科技及标准局表示,从2005年起禁止在玩具和其它儿童产品中使用邻苯二甲酸酯类的增塑剂[13].

近年来,国内外大量研究报道了血液中的PAEs浓度. 一项中国重庆人群血液的调查结果表明,DEHP在人体血液中浓度最高,平均浓度187 μg·L−1,其次为DCHP和DBP,平均浓度为125 μg·L−1 和68 μg·L-1 [14]. 而Onipede[15]关于尼日利亚孕妇血清中的PAEs浓度结果同样显示DEHP是血清中浓度最高的PAEs,高达1108 ng·mL−1. PAEs的潜在毒性以及在人体体液内的广泛存在性,使得检测血液中的PAEs浓度势在必行[16]. 由于PAEs的内分泌干扰性,现有越来越多人研究PAEs与妊娠期糖尿病(gestational diabetes mellitus, GDM)之间的关系. 目前,关于PAEs与妊娠期糖尿病之间的关系至今仍被国内外研究学者热议. 例如,黄文乐等认为产前接触PAEs可能与妊娠期糖尿病及妊娠期高血压疾病等疾病的发生、发展密切相关[17]. Kuo等在审查PAEs是否与糖尿病相关联时,发现现有的流行病学证据并不能得出两者相关的结论[18]. 因此,及时验证PAEs与妊娠期糖尿病之间的关联性是十分必要的.

在这项研究中,2011—2012年在中国杭州采集了158例孕妇血清(104例GDM孕妇和54例未患GDM孕妇),测量了血清中16种PAEs的浓度,同时用logistic和多元线性回归分析血清中PAEs的浓度和GDM以及血糖之间的相关性.

-

从2011年至2012年,从浙江省杭州市浙江大学医学院附属妇产科医院获得104例GDM孕妇和54名未患GDM孕妇的血清样本. 在专业护士的指导和帮助下,每位参与者都签署了知情同意书. 从病历系统中审查参与者的人口学特征,最终收集完整的人口学信息,包括身高、体重、年龄等. 研究方案经浙江大学医学院附属妇产科医院伦理委员会批准. 研究对象的年龄从23岁到43岁不等. GDM的诊断基于国际糖尿病和妊娠研究小组协会(IADPSG)的指南. 当参与者的空腹、1 h和2 h葡萄糖浓度分别大于0.092、0.18、0.153 mg·L−1时,将诊断为GDM. 对照组孕妇(未患GDM孕妇)的入选标准:(1)自愿参与并签署知情同意书并计划在本院分娩;(2)通过GDM诊断的受试者在怀孕期间没有出现其他重大疾病,如甲亢或重度高血压.

-

在孕妇分娩期间,受试者的全血由受过专业培训的护士采集. 在专业护士的操作下,在操作过程中从每位受试者身上采集2—3 mL全血,放入BD Vacutainer® SSTⅡ试管(Becton Dickinson,NJ,USA),在6000 r·min−1和4 ℃下离心5 min. 取上清液血浆并分装到1.5 mL BD Vacutainer®EDTA-K2管中. 采集后,进行记录并在−80 ℃的冰箱中冷冻. 在运输过程中,样品保持冷冻. 考虑到质量保证和质量控制所需的样本量,采集的现场空白样本(n = 6500 μL)与血清样本一起储存在泡沫盒中,并在4 ℃下储存在冰袋中. 所有采集的样本在提取前储存在-80 ℃的冰箱中.

-

16种邻苯二甲酸酯混标标样 (1000 μg·L−1 in Hexane):邻苯二甲酸丁基苄基酯BBP,邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙氧基)乙酯DEEP,邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基) DEHP,邻苯二甲酸二(2-甲氧基)乙酯DMEP,邻苯二甲酸二(2-丁氧基)乙酯DBEP,邻苯二甲酸二(4-甲基2-戊基)酯BMPP,邻苯二甲酸二正辛酯DNOP,邻苯二甲酸二戊酯DPP,邻苯二甲酸二环己酯DCHP,邻苯二甲酸二乙酯DEP,邻苯二甲酸二己酯DHXP,邻苯二甲酸二异丁酯DIBP,邻苯二甲酸二甲酯DMP,邻苯二甲酸二正壬酯DNP,邻苯二甲酸二丁酯DBP,邻苯二甲酸二苯酯DPHP,均购自J&K公司(中国上海). 上述16种邻苯二甲酸酯对应的混标内标则购自安谱实验技术有限公司. 正己烷,甲基叔丁基醚(MTBE)购自上海安谱技术有限公司;超纯水是在实验室中制备的.

-

以热电TRACE1300气相色谱质谱仪对样品的PAEs进行定性和定量. 色谱柱:DB-5MS(30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). 以高纯氮气(≥ 99.999%)为载气,流速为1.0 mL·min−1,进样口温度为280 ℃,程序升温为:初始柱温70 ℃,保持2 min;以10 ℃·min−1的速度将温度提高到250 ℃,持续1 min;再次以15 ℃·min−1的速度将温度提高到300 ℃,并保持5 min. 电离方式采用电子轰击电离源(EI). 16种PAEs的质谱参数如表1所示.

-

参照Sun等[19]测定血清中PAEs的方法,并将其优化. 具体步骤是将0.5 mL血清转移到15 mL玻璃离心管中,并用10 μL同位素标记的标准品进行强化. 涡旋2 min,用8 mL正己烷:MTBE (V :V = 1 :1)提取强化样品,并在超声波下处理30 min. 在4000 r·min−1下离心10 min后,将上清液转移到新的15 mL玻璃离心管中. 再次添加4 mL正己烷:MTBE萃取,将2次萃取后的上清液合并到新的15 mL玻璃离心管中,在温和的氮气下氮吹至2 mL. 用15 mL正己烷活化中性氧化铝小柱,而后将上清液过柱,而后用10 mL正己烷洗脱并收集滤液. 将滤液在温和氮气下干燥至干后用1 mL 正己烷溶液重新组合,之后涡旋1 min,以6000 r·min−1离心6 min,将上清液转移到棕色进样小瓶. 在仪器分析之前,将样品储存在-20 °C冰箱中.

-

为了减少实验造成的背景污染,在每10个样品中设置1个程序空白(n = 4,500 μL). 同时,实验中避免使用塑料制品. 实验容器由玻璃制成,用二次蒸馏水清洗,并在丙酮中浸泡1 h,最后在200 ℃烘箱中烘烤2 h,冷却至室温供使用. 采用内标法测定血样中PAEs的含量. PAEs的校准曲线呈线性关系,相关系数R2 ≥ 0.995.

PAEs的检测限(LOD)定义为3倍的信噪比(S/N). 在程序空白和溶剂空白样品中可检测到DMP、DEP、DIBP、DBP和DEHP等5种PAEs,其含量分别为10.5、10.8、18.2、31、48.5 μg·L−1. PAEs的平均提取回收率(50 μg·L−1)在74.29%—112.08%,相对标准偏差(RSD)均小于10%.

-

对受试者的人口统计学信息、血糖水平和血清PAEs浓度水平进行了初步描述性统计,低于LOD的PAEs浓度用LOD/√2 代替. 对血清中的邻苯二甲酸酯浓度进行对数转换,以实现正态分布. 所有受试者的在现有文献经常报道的协变量中,选择了以下变量:年龄(<30,30—40,>40)、BMI(<18.5,18.5—24,>24 kg·m−2)、产次(未产妇和生产1次,2次和丢失)、文化程度(高中以下,高中和大学及以上),疾病史(有或无)和家族史(有或无)最终被纳入优化模型. 在调整不同的协变量后,线性回归分析用于评估血清PAEs浓度与空腹血糖,1 h血糖和2 h血糖水平,该方法基于逐步方法来获得最佳模型. 采用logistic回归分析确定血清中PAEs浓度与GDM发病率之间的相关性. 采用SPSS 25.0对所得的研究结果进行分析,并使用错误发现率(FDR)调整后的P值进行多次比较. 经FDR校正后,P <0.05被认为具有统计学意义.

-

表2显示了参与者的人口统计学特征. 在这项研究中,超过90%的参与者的母亲第一次生育. 超过50%的母亲在大学或以上受过良好教育. 妊娠前GDM和未患GDM母亲的平均年龄分别为32岁和31岁. 曼-惠特尼检验(Mann-Whitney U检验)和卡方检验结果显示GDM组和未患GDM组两组之间的年龄和BMI有显著差异,其余变量均无显著差异.

-

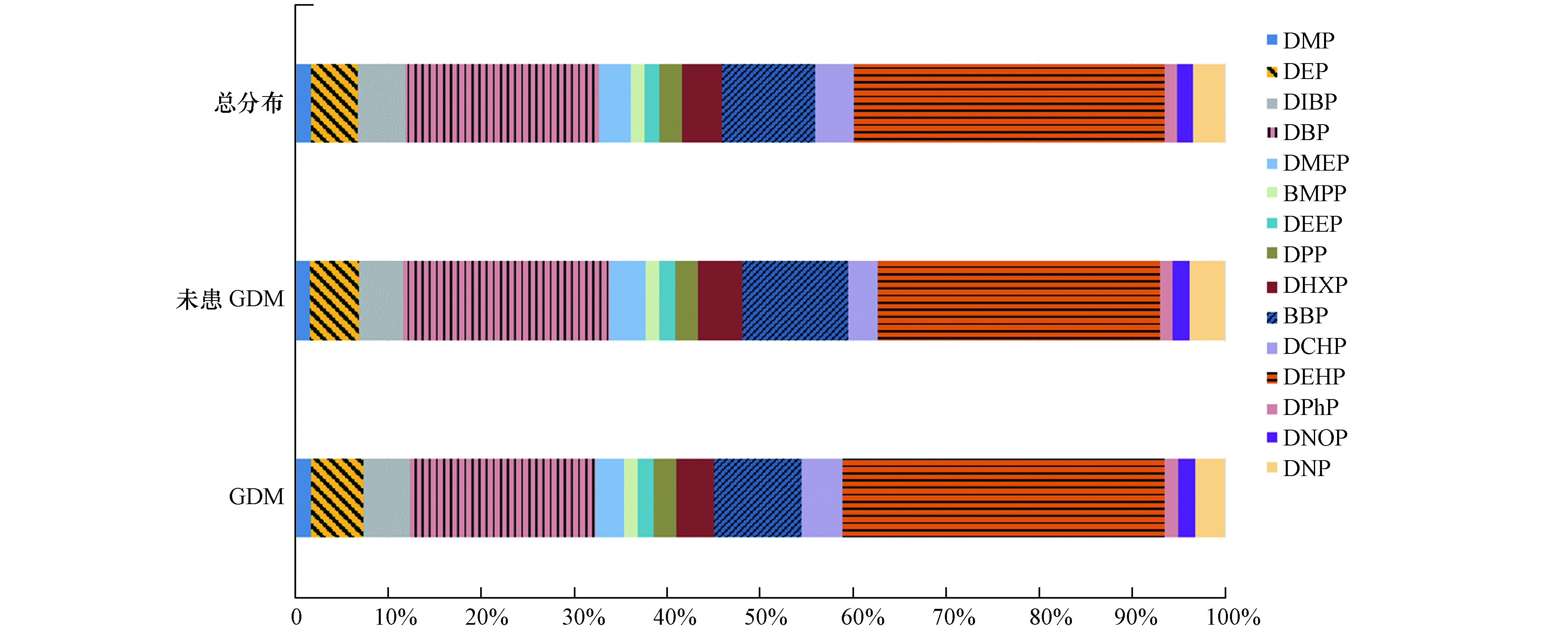

表3为受试者血清中PAEs的浓度. 实验结果显示,16种PAEs中仅检测到了15种,DBEP在血清中未检出,具体分布见图1. 在GDM组和未患GDM组的血清中,DEHP、DEP、DMP、DBP和DIBP的检出率均为100%. 结果表明,DEHP在血清中浓度最高( 32.95 ng·mL−1,范围3.91—85.71 ng·mL−1),其次是DBP(20.55 ng·mL−1,范围4.71—68.23 ng·mL−1)和BBP(9.89 ng·mL−1,范围0.68—22.72 ng·mL−1). 血清样本中BMPP(1.47 ng·mL−1)和DPHP(1.34 ng·mL−1)的平均浓度相对较低. 除DEHP、DBP、BBP、BMPP和DPHP外,还检出有DMP(1.68 ng·mL−1)、DEP(4.97 ng·mL−1)、DIBP(4.98 ng·mL−1)、DMEP(3.37 ng·mL−1)、DEEP(1.61 ng·mL−1)、DPP(2.42 ng·mL−1)、DHXP(4.23 ng·mL−1)、DCHP(4.08 ng·mL−1)、DNOP(1.73 ng·mL−1)和DNP(3.38 ng·mL−1). 在不同人群中,血液中的PAEs浓度不同. 与之前研究相比,Wan[20]指出香港人群血清中DBP浓度为0.77—12.5 ng·mL−1,低于此次研究. Chen等[21]发现,重庆产妇血清中DBP浓度为0.051—7.751 μg·mL−1,而在Lin[22]的研究中,母血中的DEHP和DBP平均浓度分别为7.67 μg·mL−1和8.84 μg·mL−1,脐带血中DEHP和DBP平均浓度分别为5.71 μg·mL−1和5.20 μg·mL−1,均远高于此次研究, 这可能与地区差异以及受试者的饮食习惯不同有关.

-

表4显示了GDM组和未患GDM组所有孕妇(n = 158)血清中15种PAEs浓度与血糖水平之间的关系. 结果呈现未调整模型和调整后模型的血清中DBP、DIBP和DEHP浓度与2 h血糖呈正相关(未调整模型:βDBP = 0.13,95%可信区间(95% CI):0.09,0.42,P <0.05;βDIBP = 0.19,95% CI:0.04,0.65,P <0.05;βDEHP = 0.32,95% CI:0.10,0.53,P <0.05. 调整后模型:βDBP = 0.12,95% CI:0.07,0.38,P <0.05;βDIBP = 0.25,95% CI:0.10,0.69,P <0.05;βDEHP = 0.38,95% CI:0.15,0.58,P <0.05),而其他12种PAEs浓度与2 h血糖无相关性,所有PAEs浓度与FBG和1 h血糖水平无统计学相关性(P >0.05). 研究对比说明,孕妇血清中的DEHP、DBP和DIBP与2 h血糖之间存在正相关性. 目前,一项关于大鼠与葡萄糖稳态的实验研究发现,7个月大的大鼠在子宫内和哺乳期间暴露于 6.25 mg·kg−1·d−1的DEHP,在禁食期间会出现高血糖和低胰岛素血症以及进行性葡萄糖耐受不良,从而造成葡萄糖代谢紊乱[23]. 另有研究报道,PAEs在人体中的暴露与血糖增加有关,有明确的迹象表明血糖水平会随着DBP、DEHP和DIBP暴露量的增加而升高[24]. 而葡萄糖代谢紊乱与β细胞功能障碍有关,与此同时也会出现胰岛素抵抗和葡萄糖耐受量受损等其他病症[25]. 已有研究表明,妊娠期暴露于DEHP和DBP与血糖、血压和母体体重增加有关[26]. 而DEHP作为最常见的PAEs之一,暴露于人体会导致其胰岛素抵抗的升高,胰岛β细胞功能的降低以及血糖控制水平减弱[27]. 同样的,Sun等[28]认为PAEs可能激活PPAR从而导致糖尿病的发生,而PPAR是葡萄糖稳态和脂质的主要调节剂. 有证据表明过氧化物酶体增殖受体 (PPARα and PPARγ)与高血脂、肥胖、糖尿病等疾病有关[29]. 造成上述不一致结果的可能原因是研究设计、研究人群、建立模型、采样时间点或样本收集的不同.

-

采用logistic回归分析,表5中未调整模型之前的分析结果显示,血清中的DMP、DIBP、DBP、DPP和DEHP都会增加孕妇患GDM的风险 (ORDMP = 1.98,95% CI:1.07,3.47;ORDIBP = 1.62,95% CI:1.30,2.70;ORDBP = 1.29,95% CI:1.07,2.37;ORDPP = 1.47,95% CI:1.08,2.02;ORDEHP = 3.97,95% CI:2.18,5.82). 在经过调整年龄,胎次,BMI,疾病史和家族史变量后,仅有血清中的DMP、DIBP、DBP和DEHP这4种物质会增加GDM的患病风险 (ORDMP = 2.39,95% CI:1.14,3.85;ORDIBP = 2.32,95% CI:1.78,4.14;ORDBP = 3.54,95% CI:1.25,5.70;ORDEHP = 4.19,95% CI:2.89,5.99). 现有许多研究报道称PAEs与GDM之间存在关联. 例如,中国[30]、美国[31]和中东地区的一些国家[32]关于PAEs与糖尿病研究指出,人体内PAEs的含量越高,糖尿病患病率越高. Radke在探究PAEs浓度与糖尿病之间的关系时发现,DEHP与患糖尿病几率之间存在较强的正相关性,DBP和DIBP与患糖尿病之间的正相关性中等,而BBP与DEP与患糖尿病的风险之间正相关性较弱[33]. Gao在其研究中指出,DBP会直接增加孕妇孕期体重,从而导致孕妇患上GDM[26]. 有研究认为GDM的发病机制主要与胰岛素抵抗和炎症因子(TNF-α)有关[34]. Friedman[35]指出血清中TNF-α(肿瘤坏死因子)水平与GDM的发生密切相关. 在GDM患者中,TNF-α水平显著升高,胰岛素抵抗的增加更为明显[36],这表明TNF-α是妊娠相关胰岛素抵抗的有效预测因子. 在Tao的最新研究证实DEHP可增加TNF-α功能,下调葡萄糖摄取过程,从而导致GDM[37]. GDM通常伴随 PPARγ 表达失调,胰岛素敏感性改变[38]. 最新的研究证实,PPARγ 突变可引起营养不良、胰岛素抵抗,与妊娠期糖尿病发病密切相关[39]. PAEs可通过各种暴露途径进入体内,通过激活PPAR调节激素表达[40],PPARγ 是葡萄糖和脂类代谢的重要调节因子,还具有抗炎、抗氧化、抗致 糖尿病因子的功能[41],通过形成PPARα-γ二聚体,激活转录因子作用于细胞内基因组,激活脂肪生成,促进脂肪细胞合成,阻断脂联素的作用,从而导致体重增加、肥胖等增加胰岛素抵抗并最终导致糖尿病等多种病症[35].

本研究的创新之处在于,当前研究的结果为关于接触PAEs与孕妇血糖水平和GDM风险之间是否存在关系等模棱两可的发现提供了积极的证据. 其次,此次研究采用血清作为样品,血清中邻苯二甲酸酯的浓度可以直接反映生物有效剂量. 第三,大多数先前的研究只关注了邻苯二甲酸酯暴露对普通人群血糖或糖尿病的影响,而很少有关于接触邻苯二甲酸酯对孕妇妊娠期糖尿病的影响的报告. 这项研究也有一些局限性. 首先是由于对照组样本量较少,这可能会影响结果的精确度,因此这只是一项初步的研究. 其次,此研究只将血糖作为判定GDM的生物指标. 第三,邻苯二甲酸酯的半衰期较短,因此可能只表明孕妇近期接触邻苯二甲酸酯的结果. 最后,其他环境化学品如有机磷酸酯以及其他潜在的残留混淆可能导致研究结果偏差.

-

在这项研究中,对158名受试者(104名GDM孕妇和54名未患GDM孕妇)的血清中16种PAEs浓度进行了测量. 同时,评估了血清中15种PAEs浓度与血糖水平以及GDM之间的相关性. 研究发现,DEHP是杭州孕妇血清中最丰富的PAEs,其次是DBP和BBP. 同时,血清中DEHP、DBP和DIBP与2 h血糖水平呈显著正相关. DBP、DIBP、DEHP和DMP这四种PAEs会增加患GDM的风险,这为暴露于PAEs会增加GDM风险提供了证据. 目前对于孕妇血清中PAEs含量与GDM之间的研究信息依旧存在不足,未来需要更多探索.

孕妇血清邻苯二甲酸酯浓度与妊娠期糖尿病之间的关系

Relationship between serum concentrations of phthalic acid esters and gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women

-

摘要: 邻苯二甲酸酯(PAEs)广泛暴露于人体,对孕妇有许多不利影响. 迄今为止,已发表了许多关于PAE对妊娠期糖尿病(GDM)风险影响的研究,但这些研究的结果存在争议. 本研究共采集了2011年至2012年158例孕妇血清样本(包括104名GDM孕妇和54名未患GDM孕妇),利用气相色谱-质谱(GC-MS)测量了血清中16种PAEs的浓度,并研究了血清中PAEs浓度与孕妇患GDM风险和血糖水平之间的关系. 结果表明,邻苯二甲酸二(2-乙基)己酯(DEHP,平均值为32.95 ng·mL−1)是孕妇血清中浓度最高的PAEs,其次是邻苯二甲酸二丁酯(DBP,平均值为20.55 ng·mL−1)和邻苯二甲酸丁基苄基酯(BBP,平均值为9.89 ng·mL−1). Logistic回归分析结果指出,孕妇血清中的邻苯二甲酸二甲酯(DMP,odds ratio(OR)= 2.39,95%置信区间(CI):1.14,3.85),DBP(OR = 3.54,95% CI:1.25,5.70),邻苯二甲酸二异丁酯(DIBP,OR = 2.32,95% CI:1.78,4.14)和DEHP(OR = 4.19,95% CI:2.89,5.99)浓度与GDM发病率呈显著正相关. 此外,孕妇的血清中DBP、DIBP和DEHP浓度与2 h血糖呈正相关(未调整模型:βDBP = 0.13,95% CI:0.09,0.42,P <0.05;βDIBP = 0.19,95% CI:0.04,0.65,P <0.05;βDEHP = 0.32,95% CI:0.10,0.53,P <0.05. 调整后模型:βDBP = 0.12,95% CI:0.07,0.38,P <0.05;βDIBP = 0.25,95% CI:0.10,0.69,P <;0.05;βDEHP = 0.38,95% CI:0.15,0.58,P <0.05). 总结而言,暴露于DBP、DIBP、DMP和DEHP可能会增加孕妇患GDM的风险.Abstract: Phthalic acid esters (PAEs) are widely present in humans and can have many adverse effects on pregnant women. To date, many studies on the effects of PAEs on the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) have been published, but the findings of these studies are controversial. In this study, 158 serum samples (including 104 pregnant women with GDM and 54 pregnant women non-GDM) were collected between 2011 and 2012. The concentrations of 16 PAEs in serum were measured by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS), and the association between PAEs concentrations in serum and GDM risk and blood glucose level of pregnant women was studied. The results showed that di (2-ethyl) hexyl phthalate (DEHP; mean = 32.95 ng·mL-1) was the abundant PAEs in serum, followed by dibutyl phthalate (DBP; mean = 20.55 ng·mL-1) and butyl benzyl phthalate (BBP; mean = 9.89 ng·mL-1). Logistic regression analysis indicated that dimethyl phthalate (DMP; odd ratio (OR) = 2.39, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.14, 3.85), DBP (OR = 3.54, 95% CI: 1.25, 5.70), di-isobutyl phthalate (DIBP; OR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.78, 4.14), and DEHP (OR = 4.19, 95% CI: 2.89, 5.99) concentrations in serum were significant positively associated with GDM. In addition, the concentrations of DBP, DIBP, and DEHP in serum of pregnant women were positively associated with 2-hour blood glucose (Crude Model: βDBP = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.42, P <0.05; βDIBP = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.65, P <0.05; βDEHP = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.10, 0.53, P <0.05. Adjusted Model: βDBP = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.38, P <0.05; βDIBP = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.10, 0.69, P <0.05; βDEHP = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.58, P <0.05). Overall, the results showed that exposure to DBP, DIBP, DMP, and DEHP may increase the risk of GDM in pregnant women.

-

-

表 1 16种邻苯二甲酸酯及其内标定量离子对

Table 1. 16 phthalate substances monitored in the present study and their acronyms,parent ions and product ions

化合物

Compounds母离子m/z

Parent ion子离子m/z

Product ion标样 DMP 163 77, 194 DEP 149 177, 105 DIBP 149 223, 104 DBP 149 223, 105 DMEP 149 149, 104 BMPP 149 167, 85 DEEP 149 149, 104 DPP 149 237, 219 DHXP 149 251, 104 BBP 149 91, 216 DBEP 149 101, 85 DCHP 149 167, 249 DEHP 149 167, 279 DPhP 225 77, 104 DNOP 149 279, 104 DNP 149 293, 167 内标 D4-DMP 167 77, 198 D4-DEP 167 181, 109 D4-DIBP 153 227, 108 D4-DBP 153 227, 109 D4-DMEP 153 153, 108 D4-BMPP 153 171, 85 D4-DEEP 153 153, 108 D4-DPP 153 241, 223 D4-DHXP 153 255, 108 D4-BBP 153 91, 210 D4-DBEP 153 105, 85 D4-DCHP 153 171, 253 D4-DEHP 153 171, 283 D4-DPhP 229 77, 108 D4-DNOP 153 283, 108 D4-DNP 153 297, 171 表 2 人口统计信息表(n = 158)

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of study population(n = 158)

GDM组

(n = 104)未患GDM组

(n = 54)P值 年龄/(岁)a 0.034* 平均值 32 ± 4.7 31 ± 4.6 ≤30 14(13.4%) 27(50.0%) >30 90(86.6%) 27(50.0%) BMI /(kg·m−2)a 30.38 ± 3.43 27.04 ± 3.30 0.041* <18.5 0(0%) 0(0%) 18.5—24 21(20.2%) 4(7.4%) >24 83(79.8%) 50(92.6%) 教育程度b 0.373 大学及以上 64(61.7%) 30(55.5%) 高中 32(30.7%) 16(29.6%) 高中以下 8(7.6%) 8(14.9%) 产次b 0.067 0 100(96.2%) 50(92.6%) ≥1 2(1.9%) 1(1.8%) 丢失 2(1.9%) 3(5.6%) 疾病史b 0.258 有 20(19.3%) 3(5.5%) 无 84(80.7%) 51(94.5%) 家族史b 0.483 有 9(8.7%) 10(18.5%) 无 95(91.3%) 44(81.5%) 注:a表示连续变量. 曼-惠特尼检验(Mann-Whitney U检验)用于比较GDM组和未患GDM组之间的差异.b表示分类变量. 卡方检验用于比较GDM组和未患GDM组之间的差异. 错误发现率(FDR)校正后,P <0.05被设定为具有统计学意义且标注*.

Note: a represents continuous variable Mann-Whitney test (Mann-Whitney U test) is used to compare the differences between GDM group and non-GDM group. b represents classification variables. Chi-square test is used to compare the differences between GDM group and non-GDM group After correction for error detection rate (FDR), P <0.05 was set as statistically significant with*.表 3 GDM组和未患GDM组(n = 158)孕妇血清中邻苯二甲酸酯浓度(ng·mL−1)

Table 3. Serum phthalate concentrations (ng·mL−1) in pregnant women in GDM and non-GDM groups (n = 158)

检出率/%

Detection rate平均值 ± 标准差

Mean ± SD中位数

Median25分位

25th75分位

75th95分位

95th范围

RangeGDM (n = 104) DMP 100 1.84 ± 1.21 1.41 1.08 2.16 4.61 0.38—6.43 DEP 100 5.92 ± 4.71 3.96 1.75 10.27 11.92 0.89—20.55 DIBP 100 5.38 ± 2.09 5.43 4.20 6.76 8.92 1.30—11.94 DBP 100 21.32 ± 13.67 17.82 10.41 28.37 50.18 4.89—68.23 DMEP 94 3.35 ± 2.15 2.58 1.38 5.16 7.20 0.38—7.72 BMPP 73 1.55 ± 1.10 1.20 0.82 2.18 3.56 0.29—5.94 DEEP 84 1.82 ± 0.71 1.72 1.30 2.22 3.28 0.89—4.27 DPP 96 2.59 ± 2.22 2.05 1.10 3.64 6.85 0.29—11.63 DHXP 96 4.35 ± 3.12 4.03 1.55 7.00 10.11 0.21—12.85 BBP 91 9.97 ± 5.46 9.64 6.22 13.61 19.26 0.78—22.72 DBEP ND DCHP 91 4.81 ± 1.89 5.08 3.57 6.06 7.77 0.44—9.59 DEHP 100 36.95 ± 15.41 35.46 25.68 48.71 65.43 4.62—75.34 DPHP 93 1.56 ± 1.11 1.42 0.83 1.87 3.29 0.29—8.80 DNOP 94 1.98 ± 1.15 1.72 1.09 2.79 4.21 0.46—5.81 DNP 97 3.40 ± 2.03 2.97 1.80 4.51 8.16 0.73—8.51 未患GDM (n = 54) DMP 100 1.37 ± 0.44 1.38 0.98 1.71 2.09 0.67—2.59 DEP 100 4.48 ± 4.41 2.23 1.78 6.48 11.69 0.89—26.76 DIBP 100 4.20 ± 1.95 4.31 2.30 5.56 8.05 1.31—9.69 DBP 100 19.08 ± 14.22 13.96 6.13 32.02 42.35 4.71—50.48 DMEP 96 3.38 ± 1.32 3.54 2.59 3.94 4.71 0.71—10.10 BMPP 78 1.36 ± 0.64 1.16 0.91 1.63 2.88 0.52—3.34 DEEP 94 1.41 ± 0.37 1.37 1.11 1.66 2.03 0.88—2.46 DPP 100 2.19 ±1.97 2.20 0.30 3.93 5.92 0.33—6.20 DHXP 96 4.06 ± 3.17 2.71 1.07 7.19 9.00 0.25—10.14 BBP 96 9.84 ± 4.80 11.69 6.38 13.94 15.64 0.68—15.86 DBEP ND DCHP 81 2.78 ± 1.51 2.60 1.62 3.86 5.11 0.53—5.82 DEHP 100 26.28 ± 9.21 24.75 7.08 34.96 49.43 3.91—85.71 DPHP 96 1.12 ± 0.64 0.98 0.60 1.68 2.39 0.28—2.52 DNOP 91 1.59 ± 0.99 1.32 0.94 1.85 4.07 0.56—5.61 DNP 98 3.29 ± 2.66 2.00 1.30 4.71 8.85 0.80—9.61 注:ND.,未检出. ND. ,not detected 表 4 GDM孕妇(n = 104)和未患GDM孕妇(n = 54)的血糖和血清中PAEs浓度的线性回归系数β(95%置信区间)

Table 4. Linear regression coefficients β (95% Confidence Interval) for blood glucose and serum concentrations of PAEs in GDM pregnant women (n = 104) and non-GDM pregnant women (n = 54)

空腹血糖

Fasting blood glucose1 h血糖

1-hour blood glucose2 h血糖

2-hour blood glucose未调整β(95% CI) 调整后β(95% CI) 未调整β(95% CI) 调整后β(95% CI) 未调整β(95% CI) 调整后β(95% CI) DMP 0.47(−0.09,1.12) 0.57(−0.19,1.22) 0.50(0.17,1.03) 0.55(0.06,0.83) 0.16(0.02,0.31) 0.34(0.13,0.95) DEP 0.36(−0.05,0.79) 0.11(−0.35,0.43) 0.25(−0.15,0.77) 0.19(−0.19,0.65) 0.18(0.01,0.45) 0.15(−0.03,0.53) DIBP 0.28(−0.01,0.57) 0.07(−0.18,0.43) 0.13(0.03,0.52) 0.39(0.09,0.62) 0.19*(0.04,0.65) 0.25*(0.10,0.69) DBP 0.17(0.04,0.21) 0.15(0.02,0.31) 0.26(0.02,0.64) 0.30(0.12,0.84) 0.13*(0.09,0.42) 0.12*(0.07,0.38) DMEP −0.14(−0.31,0.42) −0.03(−0.31,0.22) −0.06(−0.39,0.27) −0.24(−0.89,0.30) −0.27(−0.92,0.57) −0.12(−0.52,0.37) BMPP −0.18(−0.51,0.74) −0.05(−0.51,0.46) −0.32(−0.19,0.35) −0.25(−0.20,0.34) 0.28(−0.68,0.59) 0.30(−0.54,0.66) DEEP 0.09(−0.47,0.63) 0.14(−0.45,0.70) 0.11(−0.09,0.40) 0.18(0.04,0.35) 0.17(−0.02,0.44) 0.14(0.12,0.40) DPP 0.08(−0.33,0.40) 0.07(−0.31,0.36) −0.14(−0.31,0.41) 0.11(−0.29,0.47) 0.31(−0.16,0.82) 0.35(−0.10,0.86) DHXP 0.13(−0.13,0.37) 0.10(−0.12,0.35) 0.16(−0.21,0.63) 0.15(−0.19,0.58) 0.53(0.13,1.17) 0.50(0.05,0.97) BBP 0.02(−0.30,0.37) 0.05(−0.23,0.40) 0.24(0.07,0.74) 0.14(0.01,0.72) 1.25(0.09,1.64) 1.15(0.09,2.60) DCHP −0.12(−0.45,0.42) −0.07(−0.36,0.34) −0.07(−0.33,0.31) −0.03(−0.24,0.29) −0.34(−0.89,0.16) −0.25(−0.57,1.09) DEHP 0.17(0.08,0.39) 0.13(0.01,0.34) 0.13(0.02,0.34) 0.11(0.03,0.32) 0.32*(0.10,0.53) 0.38*(0.15,0.58) DPHP 0.71(−0.03,1.57) 0.12(−0.02,1.21) 0.65(−0.04,1.48) 0.53(−0.07,1.23) −0.09(−0.19,0.18) −0.13(−0.29,0.23) DNOP 0.32(−0.08,0.38) 0.29(−0.02,0.36) 0.29(−0.14,0.58) 0.20(−0.04,0.47) 0.16(0.02,0.62) 0.25(0.04,0.79) DNP 0.17(0.02,0.53) 0.26(0.04,0.54) 0.21(0.07,0.36) 0.12(0.01,0.27) 0.33(0.09,0.78) 0.27(−0.01,0.43) 注:调整后模型根据年龄、教育程度、BMI(BMI转化为lgBMI)、疾病史和家族史进行了调整. Note: The adjusted model was adjusted according to age, education level, BMI (BMI converted to lgBMI), disease history and family history. 表 5 血清中邻苯二甲酸酯的浓度和GDM之间的相关性

Table 5. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals evaluating phthalate serum concentrations

未调整模型

Crude调整后模型

Adjusted发生率(95%置信区间)

OR (95% CI)P 发生率(95%置信区间)

OR (95% CI)P DMP 1.98*(1.07,3.47) 0.029* 2.39*(1.14,3.85) 0.046* DEP 0.72(0.49,1.06) 0.094 0.94(0.82,1.14) 0.142 DIBP 1.62*(1.30,2.76) 0.010* 2.32*(1.78,4.14) 0.036* DBP 1.29*(1.07,2.37) 0.027* 3.54*(1.25,5.70) 0.047* DMEP 0.54(0.32,0.93) 0.058 0.51(0.27,1.00) 0.053 BMPP 0.92(0.73,1.15) 0.468 0.78(0.34,1.81) 0.566 DEEP 3.85(0.47,4.11) 0.236 3.26(0.48,4.66) 0.396 DPP 1.47*(1.08,2.02) 0.047* 1.52(0.97,2.12) 0.065 DHXP 1.04(0.93,1.16) 0.247 1.27(0.85,1.85) 0.250 BBP 1.15(0.92,1.68) 0.158 1.52(0.93,2.47) 0.096 DCHP 4.36(0.71,5.73) 0.842 5.51(0.73,7.08) 0.648 DEHP 3.97*(2.18,5.82) 0.025* 4.19*(2.89,5.99) 0.035* DPHP 0.41(0.15,1.14) 0.087 0.89(0.38,1.62) 0.098 DNOP 1.52(1.09,2.98) 0.462 1.03(0.91,1.14) 0.439 DNP 1.42(0.72,2.75) 0.182 1.28(0.76,2.55) 0.187 *P小于0.05. *P is less than 0.05. -

[1] 张玉环, 雷亚楠, 鲁皓, 等. 食品中邻苯二甲酸酯类塑化剂的检测技术研究进展[J]. 食品安全质量检测学报, 2021, 12(1): 202-209. ZHANG Y H, LEI Y N, LU H, et al. Research progress on the detection of phthalic acid ester plasticizers in food[J]. Journal of Food Safety & Quality, 2021, 12(1): 202-209 (in Chinese).

[2] JOHANSSON H K L, SVINGEN T, FOWLER P A, et al. Environmental influences on ovarian dysgenesis—Developmental windows sensitive to chemical exposures[J]. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2017, 13(7): 400-414. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.36 [3] KIM D H, CHOI S M, LIM D S, et al. Risk assessment of endocrine disrupting phthalates and hormonal alterations in children and adolescents[J]. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 2018, 81(21): 1150-1164. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2018.1543231 [4] LIN S, KU H Y, SU P H, et al. Phthalate exposure in pregnant women and their children in central Taiwan[J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 82(7): 947-955. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.10.073 [5] WANG Y, WANG F, XIANG L L, et al. Risk assessment of agricultural plastic films based on release kinetics of phthalate acid esters[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021, 55(6): 3676-3685. [6] LI Y T, WANG J, YANG S, et al. Occurrence, health risks and soil-air exchange of phthalate acid esters: A case study in plastic film greenhouses of Chongqing, China[J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 268: 128821. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128821 [7] WANG L Y, GU Y Y, ZHANG Z M, et al. Contaminant occurrence, mobility and ecological risk assessment of phthalate esters in the sediment-water system of the Hangzhou Bay[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 770: 144705. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144705 [8] KARABULUT G, BARLAS N. The possible effects of mono butyl phthalate (MBP) and mono (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) on INS-1 pancreatic beta cells[J]. Toxicology Research, 2021, 10(3): 601-612. doi: 10.1093/toxres/tfab045 [9] ARBUCKLE T E, FISHER M, MacPHERSON S, et al. Maternal and early life exposure to phthalates: The plastics and personal-care products use in pregnancy (P4) study[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 551/552: 344-356. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.02.022 [10] ASHWORTH M J, CHAPPELL A, ASHMORE E, et al. Analysis and assessment of exposure to selected phthalates found in children’s toys in Christchurch, New Zealand[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2018, 15(2): 200. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020200 [11] 王昱文, 柴淼, 曾甯, 等. 典型废旧塑料处置地土壤中邻苯二甲酸酯污染特征及健康风险[J]. 环境化学, 2016, 35(2): 364-372. doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2016.02.2015072005 WANG Y W, CHAI M, ZENG N, et al. Contamination and health risk of phthalate esters in soils from a typical waste plastic recycling area[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2016, 35(2): 364-372 (in Chinese). doi: 10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2016.02.2015072005

[12] WORMUTH M, SCHERINGER M, VOLLENWEIDER M, et al. What are the sources of exposure to eight frequently used phthalic acid esters in Europeans?[J]. Risk Analysis: an Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 2006, 26(3): 803-824. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00770.x [13] 广龙. 韩儿童用品将禁用邻苯二甲酸酯类增塑剂 [J]. 化工经济与信息, 2005, 9: 18. GUANG L. Phthalate plasticizers to be banned in Korean children's products [J]. Chemical Economic and Technical Information, 2005, 9: 18 (in Chinese).

[14] HUANG Y J, LI J N, GARCIA J M, et al. Phthalate levels in cord blood are associated with preterm delivery and fetal growth parameters in Chinese women[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(2): e87430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087430 [15] ONIPEDE O J, ADEWUYI G O, AYEDE A I, et al. Blood transfusion impact on levels of some phthalate esters in blood, urine and breast milk of some nursing mothers in Ibadan South-Western Nigeria[J]. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 2021, 101(5): 702-718. doi: 10.1080/03067319.2019.1671379 [16] del BUBBA M, ANCILLOTTI C, CHECCHINI L, et al. Determination of phthalate diesters and monoesters in human milk and infant formula by fat extraction, size-exclusion chromatography clean-up and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry detection[J]. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 2018, 148: 6-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.09.017 [17] 黄文乐, 麻艳艳, 钱益宇, 等. 产前邻苯二甲酸酯暴露与妊娠相关疾病的关系[J]. 浙江医学, 2019, 41(21): 2339-2342. HUANG W L, MA Y Y, QIAN Y Y, et al. Relationship between prenatal phthalate exposure and pregnancy-related diseases[J]. Zhejiang Medical Journal, 2019, 41(21): 2339-2342 (in Chinese).

[18] KUO C C, MOON K, THAYER K A, et al. Environmental chemicals and type 2 diabetes: An updated systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence[J]. Current Diabetes Reports, 2013, 13(6): 831-849. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0432-6 [19] SUN J, CHEN B, ZHANG L Q, et al. Phthalate ester concentrations in blood serum , urine and endometrial tissues of Chinese endometriosis patients[J]. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 2016, 9(2): 3808-3819 [20] WAN H T, LEUNG P Y, ZHAO Y G, et al. Blood plasma concentrations of endocrine disrupting chemicals in Hong Kong populations[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2013, 261: 763-769. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.01.034 [21] CHEN J, LIU H J, QIU Z Q, et al. Analysis of di- n-butyl phthalate and other organic pollutants in Chongqing women undergoing parturition[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2008, 156(3): 849-853. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.019 [22] LIN L, ZHENG L X, GU Y P, et al. Levels of environmental endocrine disruptors in umbilical cord blood and maternal blood of low-birth-weight infants[J]. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2008, 42(3): 177-180. [23] LIN Y, WEI J, LI Y Y, et al. Developmental exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate impairs endocrine pancreas and leads to long-term adverse effects on glucose homeostasis in the rat[J]. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2011, 301(3): E527-E538. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00233.2011 [24] CASTRO-CORREIA C, CORREIA-SÁ L, NORBERTO S, et al. Phthalates and type 1 diabetes: Is there any link?[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2018, 25(18): 17915-17919. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1997-z [25] CHEN H, ZHANG W, RUI B B, et al. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exacerbates non-alcoholic fatty liver in rats and its potential mechanisms[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2016, 42: 38-44. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.12.016 [26] GAO H, ZHU B B, HUANG K, et al. Effects of single and combined gestational phthalate exposure on blood pressure, blood glucose and gestational weight gain: A longitudinal analysis[J]. Environment International, 2021, 155: 106677. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106677 [27] DALES R E, KAURI L M, CAKMAK S. The associations between phthalate exposure and insulin resistance, β-cell function and blood glucose control in a population-based sample[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 612: 1287-1292. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.009 [28] SUN Q, CORNELIS M C, TOWNSEND M K, et al. Association of urinary concentrations of bisphenol A and phthalate metabolites with risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective investigation in the nurses’ health study (NHS) and NHSII cohorts[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2014, 122(6): 616-623. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307201 [29] DESVERGNE B, FEIGE J N, CASALS-CASAS C. PPAR-mediated activity of phthalates: A link to the obesity epidemic?[J]. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2009, 304(1/2): 43-48. [30] DONG R H, ZHAO S Z, ZHANG H, et al. Sex differences in the association of urinary concentrations of phthalates metabolites with self-reported diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in Shanghai adults[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017, 14(6): 598. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060598 [31] JAMES-TODD T, STAHLHUT R, MEEKER J D, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and diabetes among women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001-2008[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2012, 120(9): 1307-1313. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104717 [32] LI A J, MARTINEZ-MORAL M P, LABEED AL-MALKI A, et al. Mediation analysis for the relationship between urinary phthalate metabolites and type 2 diabetes via oxidative stress in a population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia[J]. Environment International, 2019, 126: 153-161. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.082 [33] RADKE E G, GALIZIA A, THAYER K A, et al. Phthalate exposure and metabolic effects: A systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence[J]. Environment International, 2019, 132: 104768. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.040 [34] JOHN C M, MOHAMED YUSOF N I S, ABDUL AZIZ S H, et al. Maternal cognitive impairment associated with gestational diabetes mellitus-a review of potential contributing mechanisms[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018, 19(12): 3894. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123894 [35] FRIEDMAN J E, KIRWAN J P, JING M, et al. Increased skeletal muscle tumor necrosis factor-alpha and impaired insulin signaling persist in obese women with gestational diabetes mellitus 1 year postpartum[J]. Diabetes, 2008, 57(3): 606-613. doi: 10.2337/db07-1356 [36] USTA M, ERTUĞ E Y, BAYTEKIN Ö, et al. Serum lipid profile and inflammatory status in women with gestational diabetes mellitus[J]. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 2016, 13(1): 45-52. [37] ZHANG T, WANG S, LI L D, et al. Associating diethylhexyl phthalate to gestational diabetes mellitus via adverse outcome pathways using a network-based approach[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 824: 153932. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153932 [38] ARCK P, TOTH B, PESTKA A, et al. Nuclear receptors of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family in gestational diabetes: From animal models to clinical trials[J]. Biology of Reproduction, 2010, 83(2): 168-176. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.083550 [39] HEUDE B, PELLOUX V, FORHAN A, et al. Association of the Pro12Ala and C1431T variants of PPARγ and their haplotypes with susceptibility to gestational diabetes[J]. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2011, 96(10): E1656-E1660. [40] McCARTHY F P, DREWLO S, ENGLISH F A, et al. Evidence implicating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia[J]. Hypertension, 2011, 58(5): 882-887. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179440 [41] BERGER J, MOLLER D E. The mechanisms of action of PPARs[J]. Annual Review of Medicine, 2002, 53: 409-435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018 -

下载:

下载: