双酚A(bisphenol A, BPA)是全球产量最高的产品之一,主要用于环氧树脂和聚碳酸酯的生产,应用于制造水杯、补牙材料、食品接触材料、涂料、管道和热敏纸等日用品[1]。体外分析和实验动物研究证明了BPA对生殖和发育、神经网络、心血管、代谢和免疫系统有不良影响[1-5],是一种环境内分泌干扰物(environmental endocrine disruptors, EEDs),被各国限制使用。因此,近年来双酚AF (bisphenol AF, BPAF)、双酚AP (bisphenol AP, BPAP)、双酚B (bisphenol B, BPB)、双酚F (bisphenol F, BPF)、双酚P (bisphenol P, BPP)、双酚S (bisphenol S, BPS)和双酚Z (bisphenol Z, BPZ)等BPA类似物作为替代品得以广泛使用。欧洲化工局报告显示,欧洲经济区BPF和BPS年生产量或进口量分别高达1 000万t和10 000万t[6]。在很多国家或地区,目前尚缺少双酚类化合物生产和使用的详细数据,但可以肯定的是,除BPA外,其他双酚类化合物(BPA类似物)的生产和应用在全球范围内都在增加[7-8]。

双酚类化合物是半持久性有机污染物,正辛醇-水分配系数和生物富集因子较高,易在生物体内蓄积,毒性效应较强[7]。相比成年人,胎儿和儿童接触双酚类化合物更多,且对暴露更为敏感。本研究首先综述双酚类化合物在环境介质、食品和人体中的污染现状,然后从生殖毒性、神经毒性、呼吸和免疫毒性、致肥胖效应和发育毒性等方面综述生命早期接触双酚类化合物产生的不良影响,为双酚类化合物特别是双酚A替代物环境质量标准制定与污染控制提供数据支撑,为提高出生人口质量、保障儿童健康提供科学依据。

1 双酚类化合物污染现状(Pollution status of bisphenols)

1.1 在环境介质中的分布

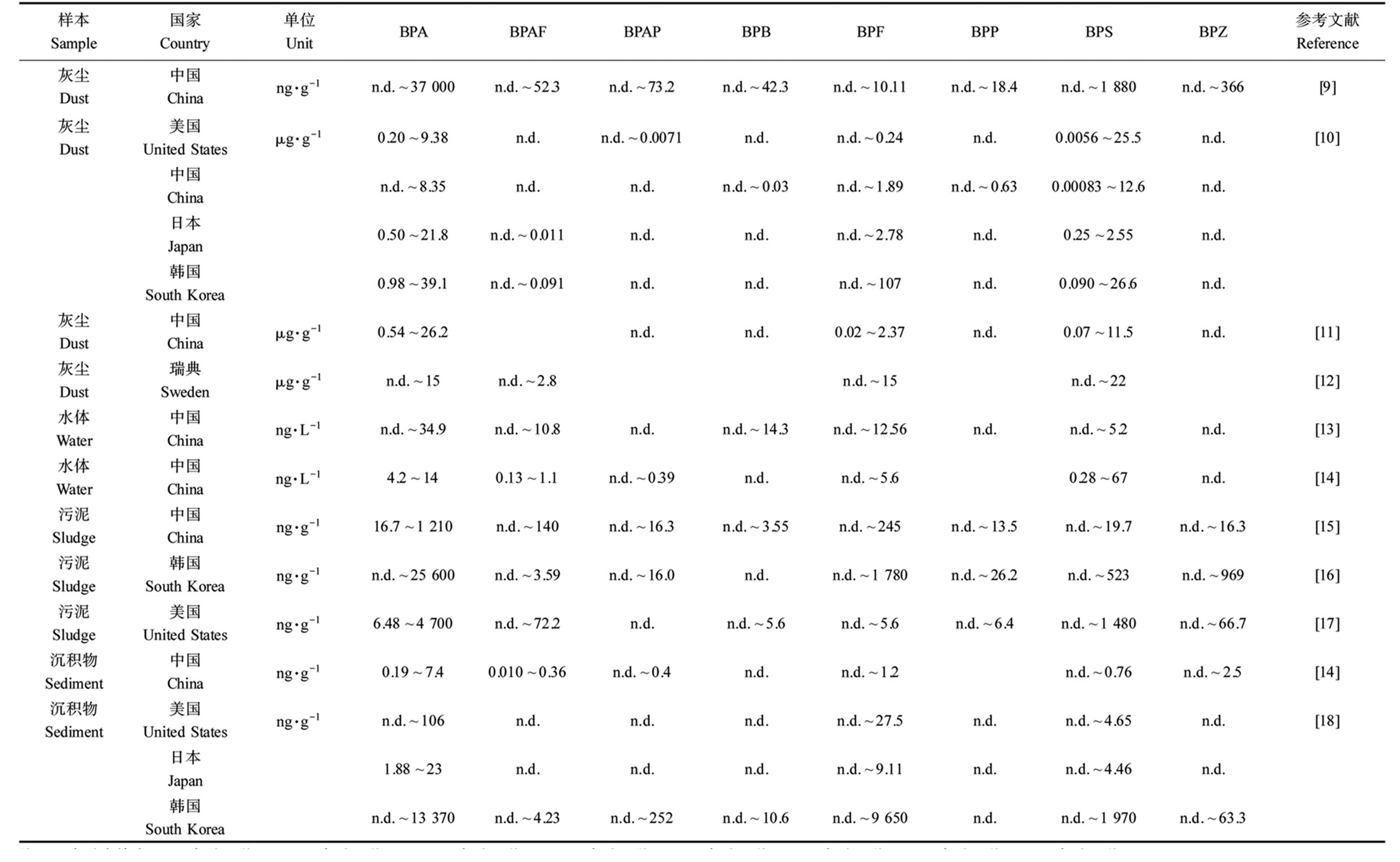

归纳总结了双酚类化合物在灰尘、水体、污泥和沉积物等环境介质中的检出浓度范围,如表1所示。迄今为止,BPA、BPAF、BPAP、BPB、BPF、BPP、BPS和BPZ等双酚类化合物在环境中有检出。

灰尘:在中国[9-11]、美国[10]、日本[10]、韩国[10]和瑞典[12]等国家的室内灰尘中,双酚类化合物均有检出。2017—2019年,我国灰尘中BPA最高检出浓度高达37 000 ng·g-1[9],与韩国相近(39.1 μg·g-1)[10],高于其他国家。

水体:在我国水体中,BPA、BPS和BPAF是检出率和检出浓度较高的双酚类化合物。2017年,我国20个饮用水处理厂水源中BPA浓度最高,可达34.9 ng·L-1,BPS检出范围为n.d.~5.2 ng·L-1[13]。辽河、浑河和太湖水体中BPA、BPS和BPAF检出率高达100%,其中BPS浓度最高(0.28~67 ng·L-1)[14]。均未超过欧盟推荐的BPA预测无效应浓度(predicted no-effect concentration, PNEC) 1 500 ng·L-1[7]。

污泥:在中国[15]、韩国[16]和美国[17]等国家的污泥中也检测出了双酚类化合物。在韩国几类污水处理厂的污泥样品中双酚类化合物平均浓度依次为:BPA (1 520 ng·g-1)、BPF (384 ng·g-1)、BPS (44.9 ng·g-1)和BPZ (24.3 ng·g-1),BPB未检出,推测主要来源于工业排放[16]。在我国城市污水处理厂的污泥中,8种双酚类化合物均有检出,检出率和检出浓度均表明BPA仍然是最主要的双酚类化合物,BPA范围为16.7~1 210 ng·g-1,BPA、BPF和BPS的检出率分别为100%、95.7%和89.1%[15]。

沉积物:双酚类化合物在中国[14]、美国[18]、韩国[18]和日本[18]临近工业区的湖泊和河流沉积物中也有检出,韩国沉积物BPA的检出浓度最高(范围为n.d.~13 700 ng·g-1),BPP未检出,美国与日本仅有BPA、BPF和BPS检出[[18]。在我国太湖流域沉积物中BPS (0.28~69 ng·L-1)的浓度高于BPA (0.19~7.4 ng·L-1)[14]。

1.2 在食品中的分布

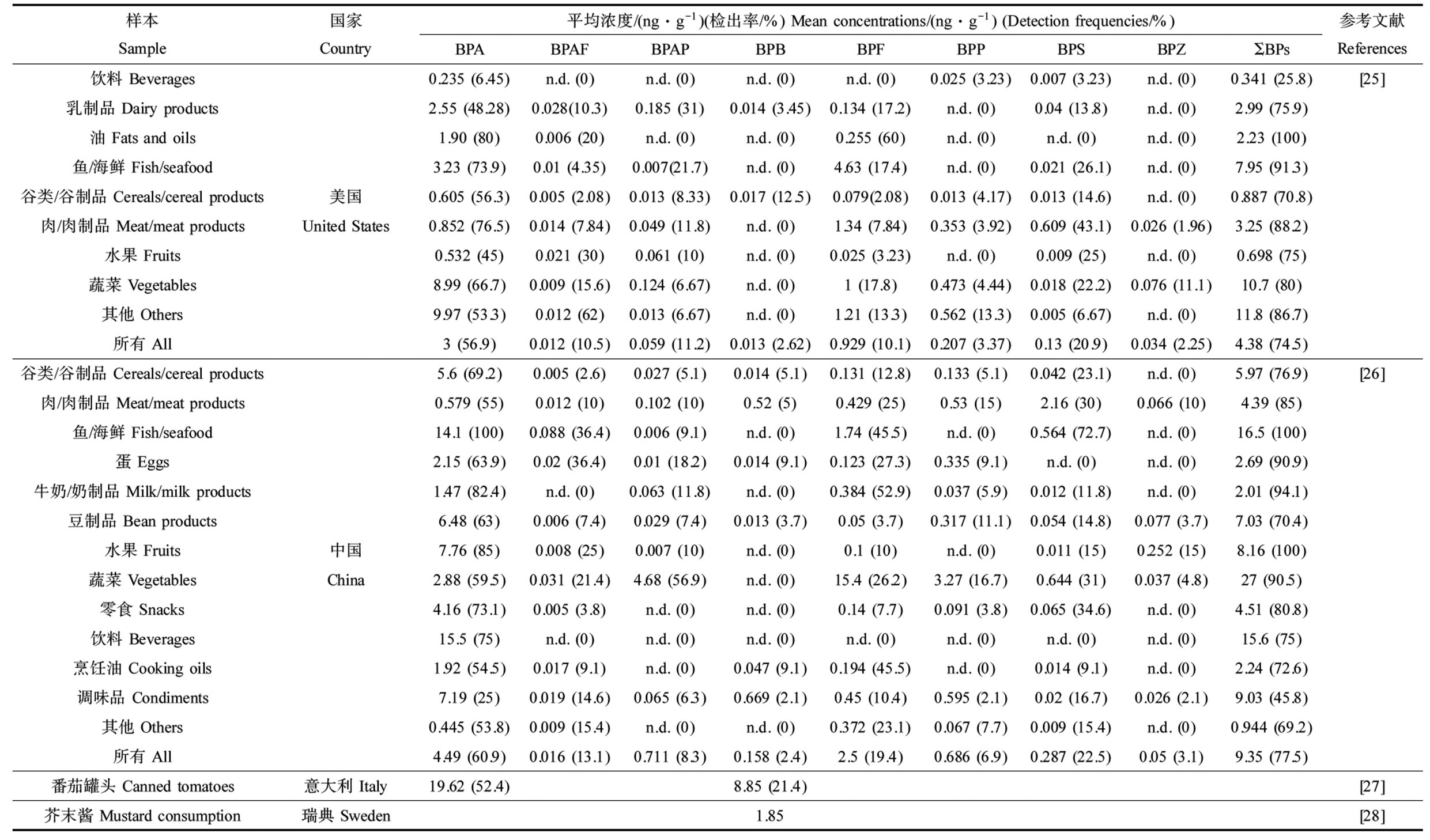

饮食是人们摄入双酚类化合物的主要途径[19-20]。用于食品接触材料或食品加工塑料的双酚类化合物可以转移到食品中[20]。摄入罐装食品和饮料与体内BPA浓度较高有关[21-22],坚持新鲜食品饮食则相反[23-24]。最近的研究也报道了来自不同国家的食品中含有BPA类似物(表2)。

在美国开展的一项包括饮料、乳制品、油脂、鱼和海鲜、肉类、谷物、水果和蔬菜的调查发现,美国食品中BPA和BPF的平均浓度分别为3 ng·g-1和0.929 ng·g-1,罐头食品比玻璃、纸或塑料容器中出售的食品含有更高浓度的单个和总双酚类化合物,统计分析时纳入罐头食品导致蔬菜中BPA浓度较高(9.97 ng·g-1)、海鲜中BPF浓度较高(4.63 ng·g-1)[25]。BPS在我国食品样品中被检出(检出率为77.5%);BPA的检出率高达60.9%,其浓度范围从

1.3 在人体中的分布

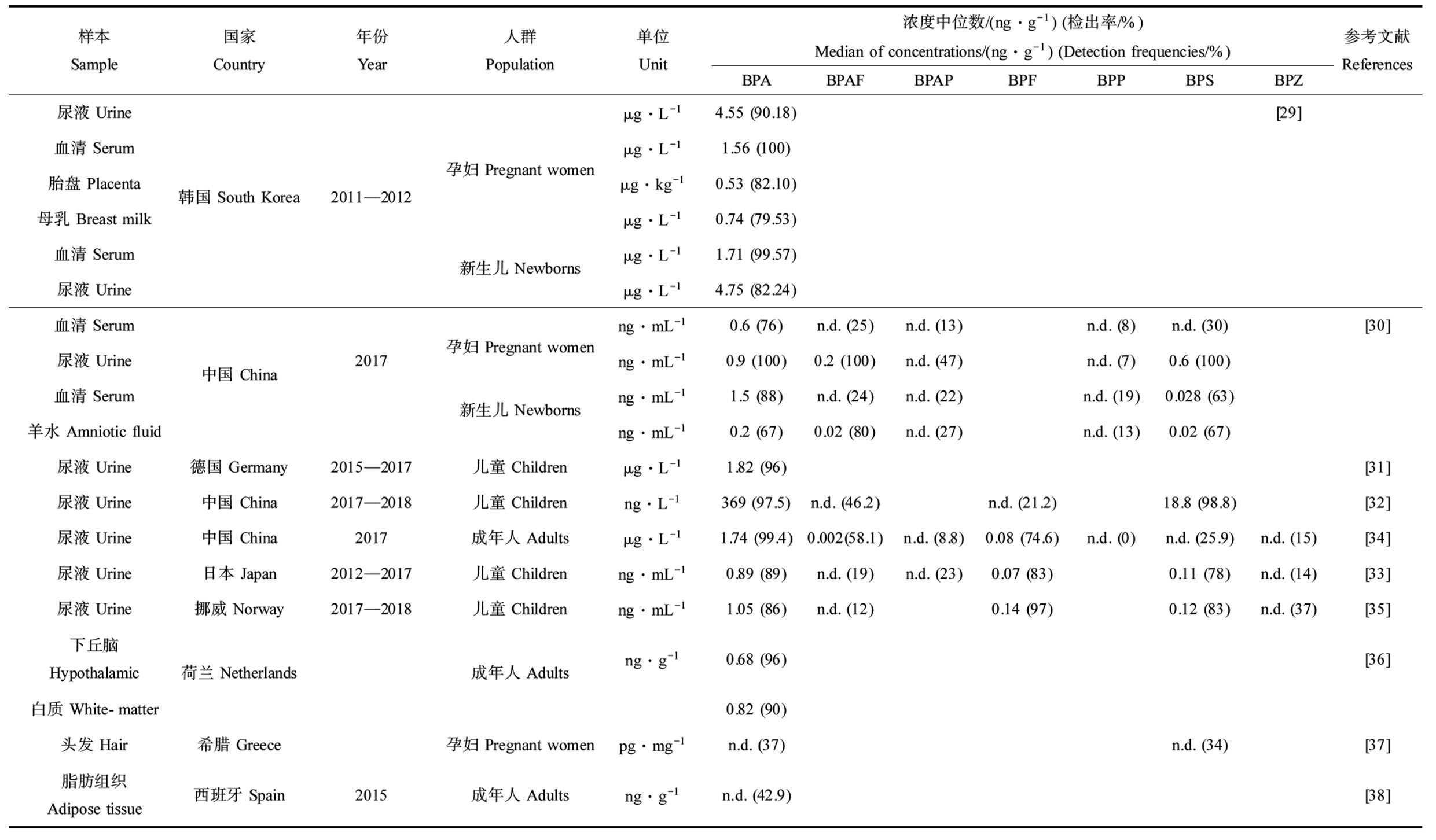

由于双酚类化合物的广泛使用,人们通过摄入、呼吸和皮肤接触双酚类化合物,目前在人的尿液、血液、胎盘、母乳、羊水、脑组织、头发和脂肪中均有检出(表3)。一项韩国研究报告了在孕妇尿液、新生儿尿液、胎盘和母乳标本中BPA检出率分别为90.2%、82.2%、82.1%和79.5%,不同样本中BPA中位浓度依次为新生儿尿液(4.75 μg·L-1)、孕妇尿液(2.86 μg·L-1)、脐带血清(1.71 μg·L-1)、孕妇血清(1.56 μg·L-1)、母乳(0.74 μg·L-1)和胎盘(0.53 μg·kg-1)[29]。居住在中国电子拆解厂附近的孕妇和新生儿体内检出5种双酚类化合物,包括BPA、BPS、BPAF、BPP和BPAP[30]。BPA是德国儿童尿液中最主要的双酚类物质,几乎所有样本中均可检出(检出率96%),中位数浓度高达1.82 μg·L-1[31]。中国南京郊区儿童尿液中BPA和BPS检出率和检出浓度最高,检出率分别为97.5%和98.8%,检出浓度中位值分别为369 ng·L-1和18.8 ng·L-1[32]。在另外3项研究中,BPF超过BPS成为BPA的主要替代物,中国成年人体内BPF检出率是BPS的3倍左右(74.6% vs. 25.9%)[33],挪威儿童体内BPF检出率超过了BPA (97% vs. 86%)[34],日本儿童体内BPF检出率高于BPS (83% vs. 78%)[35]。

此外,在欧洲成年人的脑组织(下丘脑和白质)、头发和脂肪组织中均有BPA检出:荷兰成年人下丘脑和白质中,BPA检出率分别为96%和90%,浓度中位值分别为0.68 ng·g-1和0.82 ng·g-1[36];希腊孕妇的头发中BPS的检出率(34%)与BPA相近(37%)[37];42.9%的西班牙成人脂肪组织中检出BPA[38]。

值得一提的是,上述研究的健康风险评价结果表明,危害商值(hazard quotient, HQ) (评估每种双酚类化合物单独暴露对人体的健康风险)或危害指数(hazard index, HI) (评估多种双酚类化合物联合暴露的累积健康风险)均<1,即双酚类化合物估计每日摄入量(estimated daily intake, EDI)未超过欧洲食品安全局规定的BPA每日允许摄入量(tolerable daily intake, TDI)。

2 生命早期接触双酚类化合物的不良影响(Adverse effects of early life exposure to bisphenols)

越来越多的研究表明,妊娠期、婴儿期和幼儿期的环境压力源是儿童期甚至成年期疾病的危险因素[39-40]。对生命早期的干扰,会增加数年或数十年后出现不良健康结果的风险[39-40]。相比成人,胎儿和儿童更容易受到EEDs的影响。原因一:饮食、行为、生理、解剖和毒理动力学方面的差异[41],胎儿和儿童消耗水和特定食物更多,肠道吸收率、肠道表面积与体积比更高[42],接触双酚类化合物更多;原因二:生命早期机体处于生长发育阶段,代谢解毒机制尚不完善,对外界环境干扰比成年期更敏感[43]。

2.1 生殖毒性

早在1979年,Henderson等[44]提出假说:在睾丸分化时雌激素相对过量是睾丸癌的主要危险因素。14年后,Sharpe和Skakkebaek[45]提出,不仅睾丸癌,其他男性生殖障碍如隐睾、尿道下裂、低精子数量可能共享这一假说,接触具有类雌激素效应的环境化学品可能对男性生殖障碍发生起关键作用,潜在机制是胎儿垂体负反馈的增加导致促性腺激素水平降低,从而破坏男性胎儿性腺正常发育。

实验动物学研究中,围产期SD大鼠口服BPA、BPS和BPF后,5 μg·kg-1 BPA使雌性后代卵泡数量、雄性后代肾脏和前列腺质量增加,诱导睾丸氧化应激反应;5 μg·kg-1 BPS使雌性后代排卵率和雄性后代肛门—生殖器距离降低,诱导睾丸氧化应激反应;5 μg·kg-1 BPF导致超过80%大鼠自然流产,雌性后代排卵率和雄性后代附睾脂肪组织质量降低,表明即使低剂量BPA或其类似物也会引起生殖毒性[46]。围产期暴露于高剂量BPA,其雌性子代成年期发情周期模式发生改变,血浆促黄体生成素水平降低[47]。2项Wistar大鼠的研究表明,出生后短时间暴露于超过100 mg·kg-1的BPF可增加雌性子宫相对质量,更高剂量(500 mg·kg-1) BPF暴露导致雄性睾丸质量增加[48-49]。发育早期(自妊娠第8天至产后第19天)低剂量BPS (200 μg·kg-1·d-1)暴露可影响CD-1小鼠子宫和卵巢中雌激素应答基因表达,促进雌性后代卵巢卵泡发育[4]。

表1 双酚类化合物在环境介质中的检出浓度范围

Table 1 Range of bisphenols concentrations in the environment

样本Sample国家Country单位UnitBPABPAFBPAPBPBBPFBPPBPSBPZ参考文献Reference灰尘Dust中国Chinang·g-1n.d.~37 000n.d.~52.3n.d.~73.2n.d.~42.3n.d.~10.11n.d.~18.4n.d.~1 880n.d.~366[9]灰尘Dust美国United Statesμg·g-10.20~9.38n.d.n.d.~0.0071n.d.n.d.~0.24n.d.0.0056~25.5n.d.[10]中国Chinan.d.~8.35n.d.n.d.n.d.~0.03n.d.~1.89n.d.~0.630.00083~12.6n.d.日本Japan0.50~21.8n.d.~0.011n.d.n.d.n.d.~2.78n.d.0.25~2.55n.d.韩国South Korea0.98~39.1n.d.~0.091n.d.n.d.n.d.~107n.d.0.090~26.6n.d.灰尘Dust中国Chinaμg·g-10.54~26.2n.d.n.d.0.02~2.37n.d.0.07~11.5n.d.[11]灰尘Dust瑞典Swedenμg·g-1n.d.~15n.d.~2.8n.d.~15n.d.~22[12]水体Water中国Chinang·L-1n.d.~34.9n.d.~10.8n.d.n.d.~14.3n.d.~12.56n.d.n.d.~5.2n.d.[13]水体Water中国Chinang·L-14.2~140.13~1.1n.d.~0.39n.d.n.d.~5.60.28~67n.d.[14]污泥Sludge中国Chinang·g-116.7~1 210n.d.~140n.d.~16.3n.d.~3.55n.d.~245n.d.~13.5n.d.~19.7n.d.~16.3[15]污泥Sludge韩国South Koreang·g-1n.d.~25 600n.d.~3.59n.d.~16.0n.d.n.d.~1 780n.d.~26.2n.d.~523n.d.~969[16]污泥Sludge美国United Statesng·g-16.48~4 700n.d.~72.2n.d.n.d.~5.6n.d.~5.6n.d.~6.4n.d.~1 480n.d.~66.7[17]沉积物Sediment中国Chinang·g-10.19~7.40.010~0.36n.d.~0.4n.d.n.d.~1.2n.d.~0.76n.d.~2.5[14]沉积物Sediment美国United Statesng·g-1n.d.~106n.d.n.d.n.d.n.d.~27.5n.d.n.d.~4.65n.d.[18]日本Japan1.88~23n.d.n.d.n.d.n.d.~9.11n.d.n.d.~4.46n.d.韩国South Korean.d.~13 370n.d.~4.23n.d.~252n.d.~10.6n.d.~9 650n.d.n.d.~1 970n.d.~63.3

注:n.d.表示未检出;BPA表示双酚A;BPAF表示双酚AF;BPAP表示双酚AP;BPB表示双酚B;BPF表示双酚F;BPP表示双酚P;BPS表示双酚S;BPZ表示双酚Z。

Note: n.d. means not detected; BPA means bisphenol A; BPAF means bisphenol AF; BPAP means bisphenol AP; BPB means bisphenol B; BPF means bisphenol F; BPP means bisphenol P; BPS means bisphenol S; BPZ means bisphenol Z.

表2 双酚类化合物在食品中的平均浓度和检出率

Table 2 Mean concentrations and detection frequencies of bisphenols in food

样本Sample国家Country平均浓度/(ng·g-1)(检出率/%) Mean concentrations/(ng·g-1) (Detection frequencies/%)BPABPAFBPAPBPBBPFBPPBPSBPZΣBPs参考文献References饮料 Beverages0.235 (6.45)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)0.025 (3.23)0.007 (3.23)n.d. (0)0.341 (25.8)[25]乳制品 Dairy products2.55 (48.28)0.028(10.3)0.185 (31)0.014 (3.45)0.134 (17.2)n.d. (0)0.04 (13.8)n.d. (0)2.99 (75.9)油 Fats and oils1.90 (80)0.006 (20)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)0.255 (60)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)2.23 (100)鱼/海鲜 Fish/seafood3.23 (73.9)0.01 (4.35)0.007(21.7)n.d. (0)4.63 (17.4)n.d. (0)0.021 (26.1)n.d. (0)7.95 (91.3)谷类/谷制品 Cereals/cereal products美国0.605 (56.3)0.005 (2.08)0.013 (8.33)0.017 (12.5)0.079(2.08)0.013 (4.17)0.013 (14.6)n.d. (0)0.887 (70.8)肉/肉制品 Meat/meat productsUnited States0.852 (76.5)0.014 (7.84)0.049 (11.8)n.d. (0)1.34 (7.84)0.353 (3.92)0.609 (43.1)0.026 (1.96)3.25 (88.2)水果 Fruits0.532 (45)0.021 (30)0.061 (10)n.d. (0)0.025 (3.23)n.d. (0)0.009 (25)n.d. (0)0.698 (75)蔬菜 Vegetables8.99 (66.7)0.009 (15.6)0.124 (6.67)n.d. (0)1 (17.8)0.473 (4.44)0.018 (22.2)0.076 (11.1)10.7 (80)其他 Others9.97 (53.3)0.012 (62)0.013 (6.67)n.d. (0)1.21 (13.3)0.562 (13.3)0.005 (6.67)n.d. (0)11.8 (86.7)所有 All3 (56.9)0.012 (10.5)0.059 (11.2)0.013 (2.62)0.929 (10.1)0.207 (3.37)0.13 (20.9)0.034 (2.25)4.38 (74.5)谷类/谷制品 Cereals/cereal products5.6 (69.2)0.005 (2.6)0.027 (5.1)0.014 (5.1)0.131 (12.8)0.133 (5.1)0.042 (23.1)n.d. (0)5.97 (76.9)[26]肉/肉制品 Meat/meat products0.579 (55)0.012 (10)0.102 (10)0.52 (5)0.429 (25)0.53 (15)2.16 (30)0.066 (10)4.39 (85)鱼/海鲜 Fish/seafood14.1 (100)0.088 (36.4)0.006 (9.1)n.d. (0)1.74 (45.5)n.d. (0)0.564 (72.7)n.d. (0)16.5 (100)蛋 Eggs2.15 (63.9)0.02 (36.4)0.01 (18.2)0.014 (9.1)0.123 (27.3)0.335 (9.1)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)2.69 (90.9)牛奶/奶制品 Milk/milk products1.47 (82.4)n.d. (0)0.063 (11.8)n.d. (0)0.384 (52.9)0.037 (5.9)0.012 (11.8)n.d. (0)2.01 (94.1)豆制品 Bean products6.48 (63)0.006 (7.4)0.029 (7.4)0.013 (3.7)0.05 (3.7)0.317 (11.1)0.054 (14.8)0.077 (3.7)7.03 (70.4)水果 Fruits中国7.76 (85)0.008 (25)0.007 (10)n.d. (0)0.1 (10)n.d. (0)0.011 (15)0.252 (15)8.16 (100)蔬菜 VegetablesChina2.88 (59.5)0.031 (21.4)4.68 (56.9)n.d. (0)15.4 (26.2)3.27 (16.7)0.644 (31)0.037 (4.8)27 (90.5)零食 Snacks4.16 (73.1)0.005 (3.8)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)0.14 (7.7)0.091 (3.8)0.065 (34.6)n.d. (0)4.51 (80.8)饮料 Beverages15.5 (75)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)15.6 (75)烹饪油 Cooking oils1.92 (54.5)0.017 (9.1)n.d. (0)0.047 (9.1)0.194 (45.5)n.d. (0)0.014 (9.1)n.d. (0)2.24 (72.6)调味品 Condiments7.19 (25)0.019 (14.6)0.065 (6.3)0.669 (2.1)0.45 (10.4)0.595 (2.1)0.02 (16.7)0.026 (2.1)9.03 (45.8)其他 Others0.445 (53.8)0.009 (15.4)n.d. (0)n.d. (0)0.372 (23.1)0.067 (7.7)0.009 (15.4)n.d. (0)0.944 (69.2)所有 All4.49 (60.9)0.016 (13.1)0.711 (8.3)0.158 (2.4)2.5 (19.4)0.686 (6.9)0.287 (22.5)0.05 (3.1)9.35 (77.5)番茄罐头 Canned tomatoes意大利 Italy19.62 (52.4)8.85 (21.4)[27]芥末酱 Mustard consumption瑞典 Sweden1.85[28]

注:n.d.表示未检出;BPA表示双酚A;BPAF表示双酚AF;BPAP表示双酚AP;BPB表示双酚B;BPF表示双酚F;BPP表示双酚P;BPS表示双酚S;BPZ表示双酚Z;ΣBPs表示总双酚类化合物。

Note: n.d. means not detected; BPA means bisphenol A; BPAF means bisphenol AF; BPAP means bisphenol AP; BPB means bisphenol B; BPF means bisphenol F; BPP means bisphenol P; BPS means bisphenol S; BPZ means bisphenol Z; ΣBPs means sum of bisphenols.

表3 双酚类化合物在人体中的暴露水平(中位数)和检出率

Table 3 Exposure levels (median) and detection frequencies of bisphenols in human

样本Sample国家Country年份Year人群Population单位Unit浓度中位数/(ng·g-1) (检出率/%) Median of concentrations/(ng·g-1) (Detection frequencies/%)BPABPAFBPAPBPFBPPBPSBPZ参考文献References尿液 Urineμg·L-14.55 (90.18)[29]血清 Serumμg·L-11.56 (100)胎盘 Placenta韩国 South Korea2011—2012孕妇 Pregnant womenμg·kg-10.53 (82.10)母乳 Breast milkμg·L-10.74 (79.53)血清 Serum新生儿 Newbornsμg·L-11.71 (99.57)尿液 Urineμg·L-14.75 (82.24)血清 Serumng·mL-10.6 (76)n.d. (25)n.d. (13)n.d. (8)n.d. (30)[30]尿液 Urine中国 China2017孕妇 Pregnant womenng·mL-10.9 (100)0.2 (100)n.d. (47)n.d. (7)0.6 (100)血清 Serum新生儿 Newbornsng·mL-11.5 (88)n.d. (24)n.d. (22)n.d. (19)0.028 (63)羊水 Amniotic fluidng·mL-10.2 (67)0.02 (80)n.d. (27)n.d. (13)0.02 (67)尿液 Urine德国 Germany2015—2017儿童 Childrenμg·L-11.82 (96)[31]尿液 Urine中国 China2017—2018儿童 Childrenng·L-1369 (97.5)n.d. (46.2)n.d. (21.2)18.8 (98.8)[32]尿液 Urine中国 China2017成年人 Adultsμg·L-11.74 (99.4)0.002(58.1)n.d. (8.8)0.08 (74.6)n.d. (0)n.d. (25.9)n.d. (15)[34]尿液 Urine日本 Japan2012—2017儿童 Childrenng·mL-10.89 (89)n.d. (19)n.d. (23)0.07 (83)0.11 (78)n.d. (14)[33]尿液 Urine挪威 Norway2017—2018儿童 Childrenng·mL-11.05 (86)n.d. (12)0.14 (97)0.12 (83)n.d. (37)[35]下丘脑 Hypothalamic荷兰 Netherlands成年人 Adultsng·g-10.68 (96)[36]白质 White-matter0.82 (90)头发 Hair希腊 Greece孕妇 Pregnant womenpg·mg-1n.d. (37)n.d. (34)[37]脂肪组织 Adipose tissue西班牙 Spain2015成年人 Adultsng·g-1n.d. (42.9)[38]

注:n.d.表示未检出;BPA表示双酚A;BPAF表示双酚AF;BPAP表示双酚AP;BPB表示双酚B;BPF表示双酚F;BPP表示双酚P;BPS表示双酚S;BPZ表示双酚Z。

Note: n.d. means not detected; BPA means bisphenol A; BPAF means bisphenol AF; BPAP means bisphenol AP; BPB means bisphenol B; BPF means bisphenol F; BPP means bisphenol P; BPS means bisphenol S; BPZ means bisphenol Z.

2.2 神经毒性

神经元的发育过程(包括增殖、迁移、分化、突触发生、髓鞘形成和凋亡)从胚胎期一直延续到青春期[50]。大量研究表明,双酚类化合物暴露可引起中枢神经系统发育和功能异常,包括神经可塑性改变、神经发育不良、神经细胞凋亡和认知功能障碍[51-52]。比如,长期暴露于BPA (0.1、0.5、1、5和10 μmol·L-1),人谷氨酸神经元的神经突触生长呈浓度依赖性减少,高浓度BPA (1 μmol·L-1和10 μmol·L-1)使树突的总长度和分枝数减少,顶端树突的分枝数减少[52]。细胞内Ca2+信号对突触可塑性起重要作用,BPA对海马神经元中谷氨酸诱导c(Ca2+)升高有影响:1~10 pmol·L-1时BPA抑制谷氨酸诱导c(Ca2+)升高,1~100 nmol·L-1时会增强谷氨酸诱导c(Ca2+)升高[53]。青春期小鼠暴露于BPA,降低成年期雄性小鼠社交能力,抑制其与异性社会交往,这可能是因为BPA具有弱雌激素效应[54]。青春期雄性小鼠暴露于BPA,其成年期脑内睾酮水平和外侧隔、杏仁核、终纹床核的雄激素受体(AR)水平,以及杏仁核和终纹床核的雌激素受体α和β (ERα/β)水平下调,扰乱雌性激素和雄性激素对精氨酸加压素(arginine vasopressin, AVP)系统的调节,损害雄性小鼠的社会认知能力[55]。BPA和BPS短期暴露会导致斑马鱼(Danio rerio)受精后24 h胚胎神经数量显著增加,并进一步诱导幼虫行为亢进[56]。斑马鱼暴露于BPF,幼鱼的星形胶质细胞或小胶质细胞被激活,在0.5 μg·L-1 BPF暴露水平下中枢神经细胞凋亡,不同浓度的BPF均可显著影响斑马鱼受精72 h时运动神经元的发育,并抑制轴突生长[5]。用极低剂量的BPA和BPS处理斑马鱼胚胎,下丘脑内神经元的发生分别增加了180%和240%,与运动过度活跃有关[56]。

甲状腺激素在妊娠期和儿童期的神经元迁移、突触发生和髓鞘形成中起关键作用[57]。妊娠期小鼠口服BPA母鼠和胎鼠血清中甲状腺素和三碘甲状腺原氨酸水平均低于对照组,促甲状腺素水平高于对照组[58]。

一些流行病学研究也发现双酚类化合物对儿童认知、行为等有影响。148名新生儿脐带血中BPA浓度与其7岁时的智商分数、言语理解能力指数以及知觉推理指数呈负相关[59]。Braun等[60]发现BPA浓度增加1倍,男孩的工作记忆能力得分会下降1分,而女孩的工作记忆能力会提高0.5分。自闭症谱系障碍儿童体内BPA的浓度是正常儿童的3倍[61]。

2.3 呼吸和免疫毒性

环境污染物破坏发育中的呼吸和免疫系统,可能降低抗感染能力和肺功能,增加过敏风险。BPF和BPS增加斑马鱼早期发育阶段活性氧含量、一氧化氮含量、一氧化氮合酶活性、细胞因子和趋化因子以及免疫相关基因的表达,此外BPS和BPF均可诱导雌激素受体和核转录因子(nf-κb)的表达,而雌激素受体和nf-κb拮抗剂可阻断免疫相关基因的表达,表明BPS和BPF对鱼类免疫应答功能有影响[3]。BPA (0.1 μg·L-1)显著干扰鲤鱼(Cyprinus carpio)幼鱼免疫应答[62],增加斑马鱼幼鱼先天免疫相关基因表达[63]。产前暴露于BPA使雄性大鼠的相对胸腺质量降低[64]。

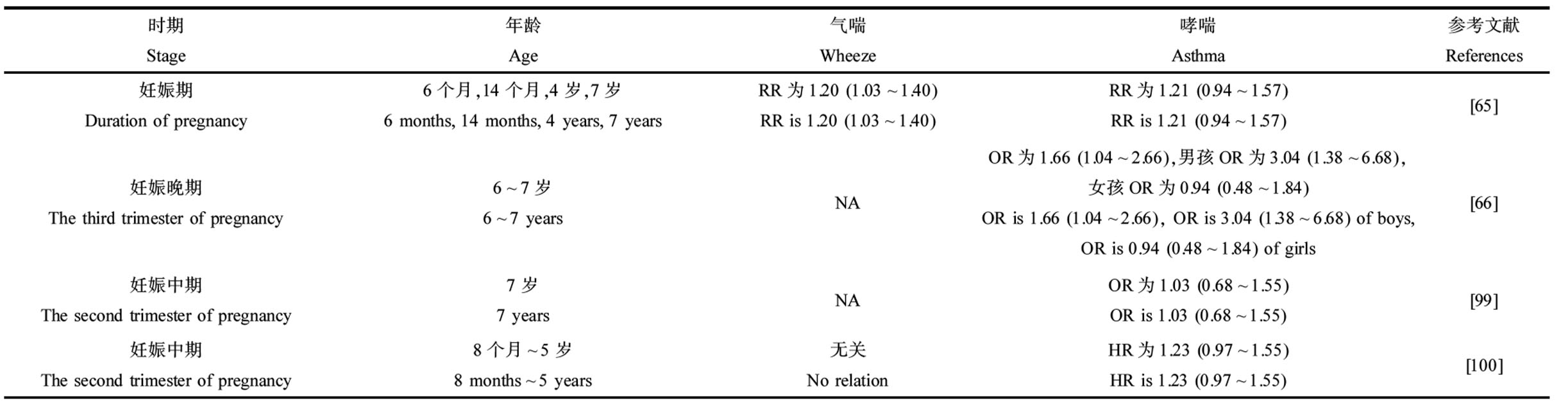

流行病学研究表明,产前暴露于BPA对儿童的气喘和哮喘有影响(表4)。妊娠期母亲尿液中BPA的浓度与儿童发生气喘的风险正相关(相对风险度(relative ratio, RR)为1.20)[65]。各个妊娠期母亲尿液中BPA的浓度水平与儿童期哮喘发生风险呈正相关,且在Buckley等[66]的研究中,这种关联仅在男孩中发现(比值比(odds ratio, OR)为3.04)。产后暴露于BPA表现出类似的影响。例如,Kim等[67]发现韩国7~8岁儿童BPA尿液浓度与气喘(OR为2.48)和哮喘(风险比(hazard ratio, HR)为2.13)发生呈正相关;哥伦比亚568名儿童尿液BPA与7岁时的气喘发生相关(OR为1.4)[68]。

2.4 致肥胖效应

生命早期暴露于EEDs可扰乱涉及生长、能量代谢、食欲、脂肪生成和糖-胰岛素稳态的神经内分泌系统,从而促进儿童肥胖[39,69-70]。Héliès-Toussaint等[71]报道了BPA或BPS处理小鼠3T3-L1脂肪细胞后,脂肪分解减少,而BPS处理增加了葡萄糖摄取和瘦素生成。这些结果表明BPA和BPS通过不同代谢途径参与肥胖和脂肪变性。

围产期暴露于BPS使小鼠的雄性后代体质量、肝脏和附睾白色脂肪组织质量、肝脏甘油三酯和胆固醇含量升高[72]。一项元分析研究表明,生命早期暴露于BPA与啮齿动物的肥胖体质量、甘油三酯和游离脂肪酸呈显著正相关[73]。

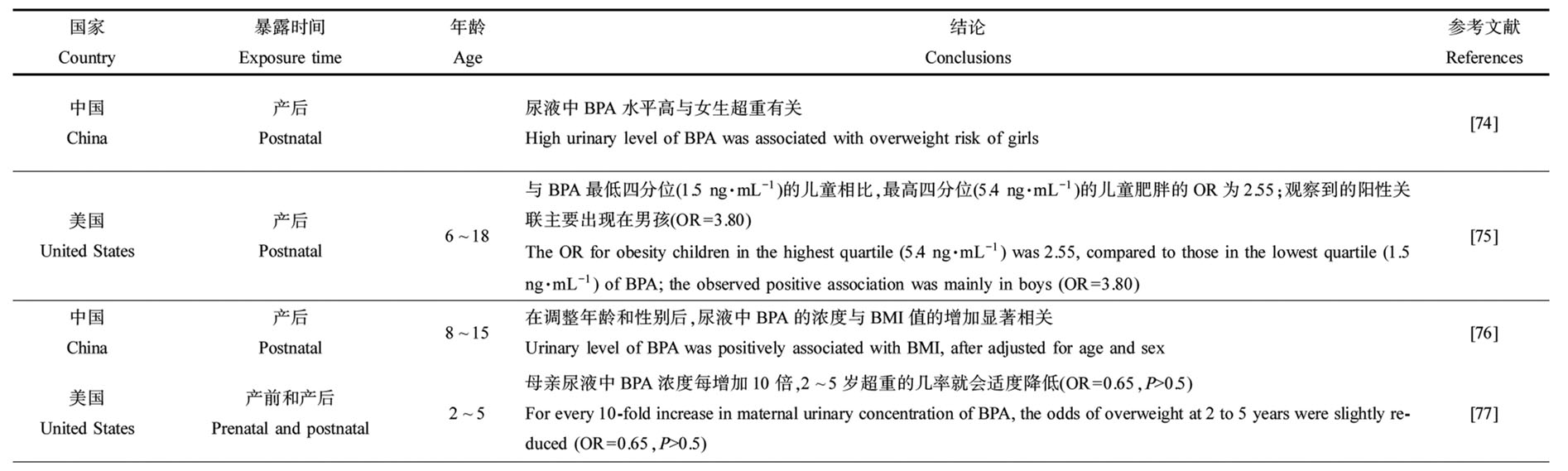

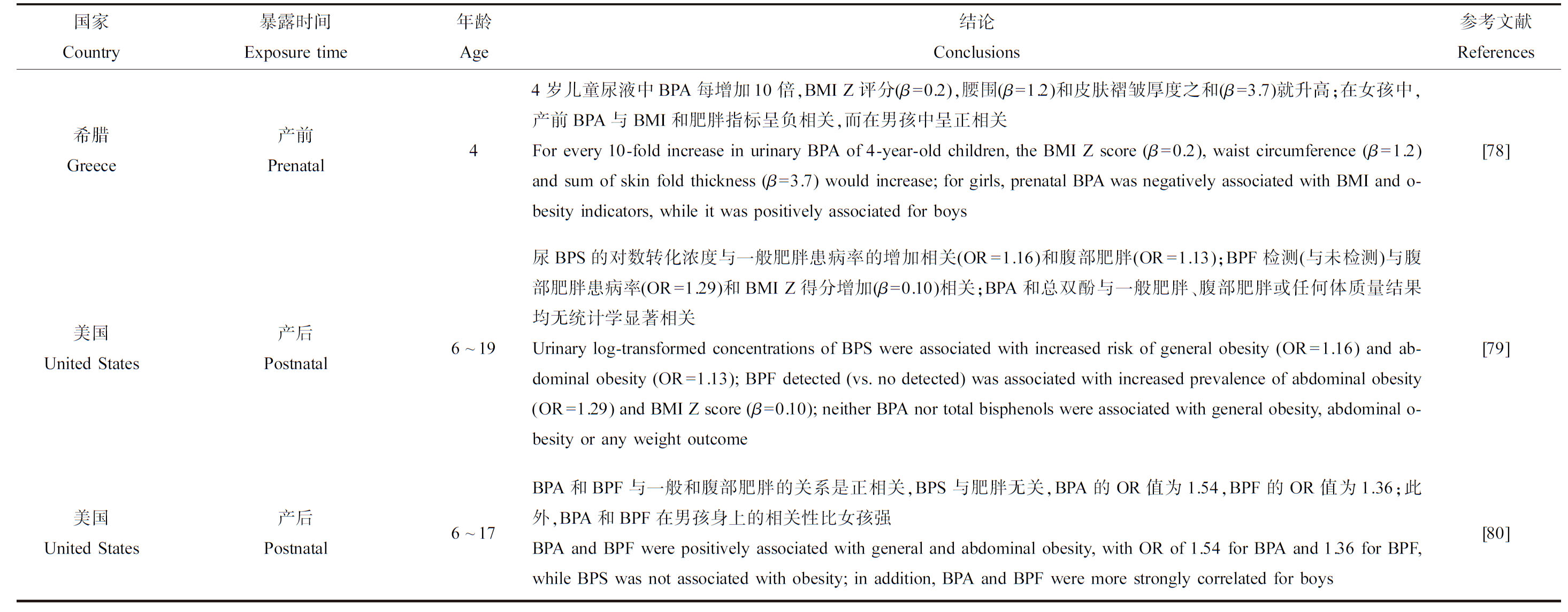

由表5可知,产前和产后暴露于酚类化合物对儿童和青少年超重或肥胖有影响。中国上海1 326名儿童尿液中高浓度BPA与女学生超重有相关性,特别是9~12岁女孩(OR=2.32)[74]。2 664名7~11岁美国儿童尿液中高浓度的BPA与肥胖的风险正相关(OR=2.55),性别分层后,在男孩中这种效应更明显[75]。一项横断面研究发现,女性和8~11岁儿童尿液中BPA的浓度与BMI值的增加显著相关[76]。在297名美国儿童的研究中,产前BPA浓度与儿童BMI无相关性[77]。在一项关于希腊儿童的研究中,产前BPA浓度与女孩BMI和肥胖指标呈负相关,而在男孩中呈正相关[78]。目前只有2项研究探究了BPA替代物对儿童和青少年肥胖或超重的影响,这2项研究中,BPF与儿童一般肥胖和腹部肥胖呈正相关[79-80]。

2.5 发育毒性

双酚类化合物可以影响新生儿出生结局,包括出生体质量和胎龄。双酚类化合物具有雌激素效应,与雌激素相关受体-g结合,影响胎盘功能[81],或者增加孕妇氧化应激反应和不良炎症,影响胚胎着床、胎盘着床和胎儿生长,如宫内生长受限、早产和低出生体质量[82-84]。BPS可以提高黄体酮水平,而黄体酮对维持妊娠状态和控制分娩起重要作用[85-86]。

动物学实验证明,亚致死浓度的BPS和BPF抑制斑马鱼幼鱼孵化时间和体长[3]。Qiu等[87]发现,低剂量BPA会缩短斑马鱼孵化时间。Yang等[88]发现,暴露于BPF会降低斑马鱼幼鱼出生体质量和出生长度。在大鼠妊娠第1~15天腹腔注射BPA,胎儿存活率下降,存活胎儿体质量下降[89]。

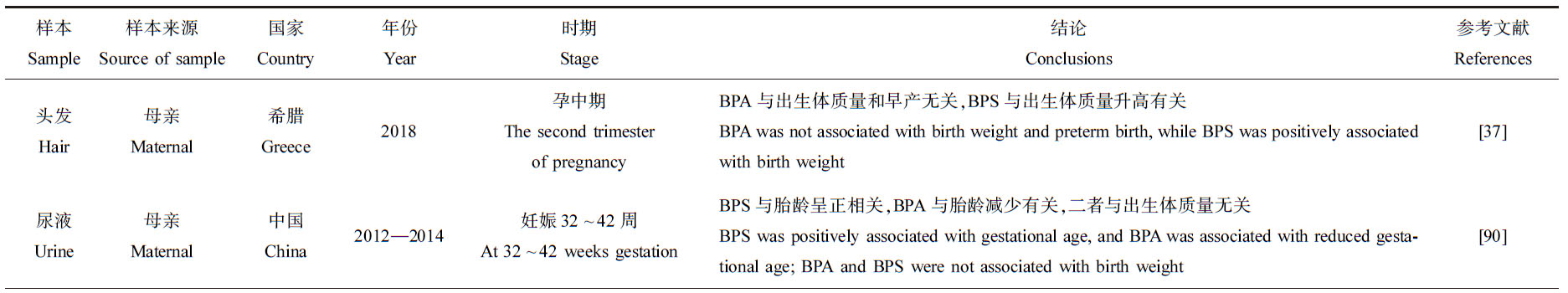

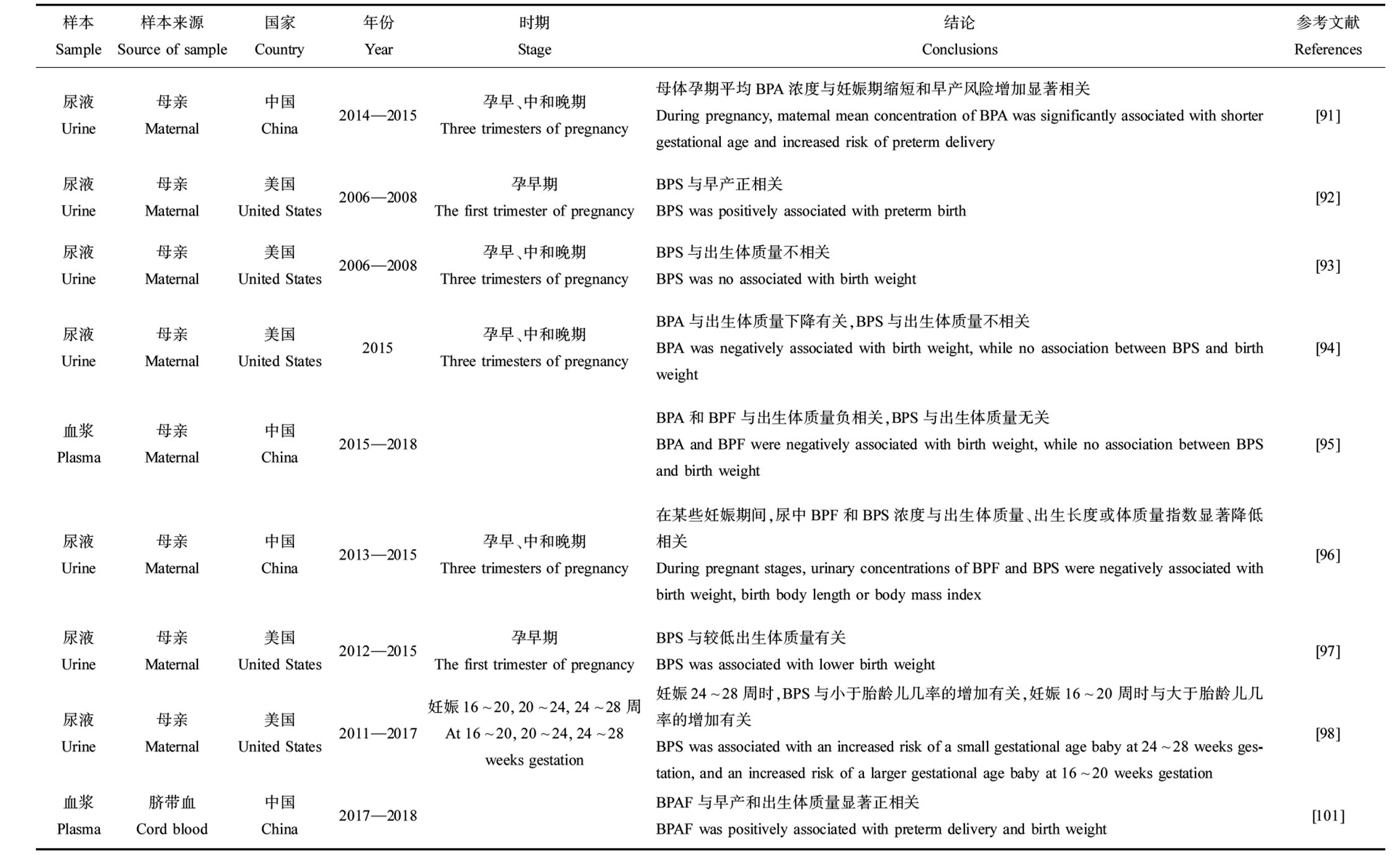

总结了产前暴露于双酚类化合物对新生儿胎龄和出生体质量影响的流行病学研究(表6),不同研究得出的结论有诸多不一致之处。在一项关于中国健康婴儿的队列研究中,母亲BPS的浓度水平与新生儿胎龄呈正相关[90],一项关于中国武汉的孕妇研究中BPS与早产没有关系[91],而在另一项研究中BPS与早产呈正相关[92]。在3项研究中,母亲尿液中BPS的浓度与出生体质量无关[93-95],而在另外3项研究中母亲体内BPS的浓度与出生体质量升高或降低有关[37,96-97]。BPA对出生体质量的影响也不一致,呈负相关或无相关性[90,94-95]。在同一篇研究中,不同妊娠时期,双酚类化合物暴露浓度对新生儿出生结局的影响也不同[98]。在美国PROTECT队列中,孕妇在妊娠24~28周时尿液中BPS浓度增加了小于胎龄儿风险,而在妊娠16~20周时BPS浓度与大于胎龄儿的风险呈正相关[98]。

3 研究展望(Research prospect)

(1) 有必要建立起一套标准化的检测方法

目前,在探究儿童体内暴露水平时,不同研究取样时间、检测方法等都存在一定差异,从而导致在进行暴露水平时空差异对比时存在一定的误差。例如,虽然大多数研究都以儿童第一次晨尿为样本,但未规定具体取样时间以及是否在进食前取样。研究证实,研究对象是否进食、取样时间与进餐时间之差会影响尿液中BPA总浓度[102]。此外,不同的前处理方法、化学检测方法导致检出限不尽相同。使用甲基叔丁基醚萃取美国儿童尿液中双酚类化合物,BPF检出限为0.074 ng·mL-1,检出率为23.6%[103];而使用固相萃取柱萃取日本儿童尿液中双酚类化合物,BPF检出限为0.02 ng·mL-1,检出率为83%[33]。除了研究对象本身的差异,检出限的不同可能也是造成检出率差异的原因之一。因此,有必要建立起一套标准化的检测方法,统一取样细节,规范分析方法,使得在进行不同研究的双酚类化合物检出情况比较时,结果更为客观准确。

(2) 应尽快开展BPA替代物对儿童体格发育影响的环境流行病学研究

小鼠动物实验与元分析研究已经明确了生命早期暴露于BPA及其主要替代物的致肥胖效应[71-73]。然而,目前对于双酚类化合物对儿童体格发育影响的环境流行病学集中于BPA[74-78],仅有2项研究探究了BPA替代物对美国儿童和青少年体格发育的影响[79-80]。儿童肥胖被确定为21世纪严重的公共卫生挑战之一。以我国为例,在过去的40年里,我国超重和肥胖儿童的数量迅速增加[104]。2005年,0~6岁儿童的超重率为3.4%,肥胖率为2.0%,7~17岁儿童和青少年超重率为4.5%,肥胖率为2.1%[105]。2015—2019年,中国6岁以下儿童超重率为6.8%,肥胖率为3.6%;6~17岁儿童和青少年超重率为11.1%,肥胖率为7.9%[104]。考虑到BPA替代物日益广泛的使用、在环境和人体中的生物迁移和生物放大作用,以及儿童超重率、肥胖率的大幅增加,应尽快开展其对儿童体格发育的影响研究。

(3) 有必要开展胎儿脐带血中双酚类化合物实测浓度对新生儿出生结局影响的研究

双酚类化合物可以透过胎盘屏障,直接对胎儿产生影响。但是,由于暴露方式等因素的变化,双酚类化合物的胎盘转运率(即胎儿血浆与母亲血浆浓度的比值)波动较大。例如,Zhang等[30]发现BPS、BPA的胎盘转运率分别为1.11、1.94;而在绵羊的胎盘灌注模型中,BPS的胎盘转运率为0.032[106],BPA的胎盘转运率为0.293[107]。因此,以孕妇体内双酚类化合物的浓度代表胎儿的产前暴露水平,可能会低估或高估双酚类化合物对新生儿出生结局的影响,这可能是造成目前不同研究结论不一致的原因之一(表6)。因此,有必要开展胎儿脐带血中双酚类化合物实测浓度对新生儿出生结局影响的研究。

表4 产前暴露于BPA对儿童气喘和哮喘的影响

Table 4 Effect of prenatal exposure to BPA on wheeze and asthma of children

时期Stage年龄Age气喘Wheeze哮喘Asthma参考文献References妊娠期Duration of pregnancy6个月,14个月,4岁,7岁6 months, 14 months, 4 years, 7 yearsRR为1.20 (1.03~1.40)RR is 1.20 (1.03~1.40)RR为1.21 (0.94~1.57)RR is 1.21 (0.94~1.57)[65]妊娠晚期The third trimester of pregnancy6~7岁6~7 yearsNAOR为1.66 (1.04~2.66),男孩OR为3.04 (1.38~6.68),女孩OR为0.94 (0.48~1.84)OR is 1.66 (1.04~2.66), OR is 3.04 (1.38~6.68) of boys, OR is 0.94 (0.48~1.84) of girls[66]妊娠中期The second trimester of pregnancy7岁7 yearsNAOR为1.03 (0.68~1.55)OR is 1.03 (0.68~1.55)[99]妊娠中期The second trimester of pregnancy8个月~5岁8 months~5 years无关No relationHR为1.23 (0.97~1.55)HR is 1.23 (0.97~1.55)[100]

注:NA表示未进行分析;OR表示比值比;HR表示风险比;RR表示相对风险度;BPA表示双酚A。

Note: NA means no analysis; OR means odds ratio; HR means risk ratio; RR means relative risk; BPA means bisphenol A.

表5 产前和产后暴露于双酚类化合物对儿童和青少年肥胖和超重的影响

Table 5 Effect of prenatal and postnatal exposure to bisphenols on childhood obesity and overweight

续表5

国家Country暴露时间Exposure time年龄Age结论Conclusions参考文献References中国China产后Postnatal尿液中BPA水平高与女生超重有关High urinary level of BPA was associated with overweight risk of girls[74]美国United States产后Postnatal6~18与BPA最低四分位(1.5 ng·mL-1)的儿童相比,最高四分位(5.4 ng·mL-1)的儿童肥胖的OR为2.55;观察到的阳性关联主要出现在男孩(OR=3.80)The OR for obesity children in the highest quartile (5.4 ng·mL-1) was 2.55, compared to those in the lowest quartile (1.5 ng·mL-1) of BPA; the observed positive association was mainly in boys (OR=3.80)[75]中国China产后Postnatal8~15在调整年龄和性别后,尿液中BPA的浓度与BMI值的增加显著相关Urinary level of BPA was positively associated with BMI, after adjusted for age and sex[76]美国United States产前和产后Prenatal and postnatal2~5母亲尿液中BPA浓度每增加10倍,2~5岁超重的几率就会适度降低(OR=0.65,P>0.5)For every 10-fold increase in maternal urinary concentration of BPA, the odds of overweight at 2 to 5 years were slightly reduced (OR=0.65,P>0.5)[77]希腊Greece产前Prenatal44岁儿童尿液中BPA每增加10倍,BMI Z评分(β=0.2),腰围(β=1.2)和皮肤褶皱厚度之和(β=3.7)就升高;在女孩中,产前BPA与BMI和肥胖指标呈负相关,而在男孩中呈正相关For every 10-fold increase in urinary BPA of 4-year-old children, the BMI Z score (β=0.2), waist circumference (β=1.2) and sum of skin fold thickness (β=3.7) would increase; for girls, prenatal BPA was negatively associated with BMI and o-besity indicators, while it was positively associated for boys[78]美国United States产后Postnatal6~19尿BPS的对数转化浓度与一般肥胖患病率的增加相关(OR=1.16)和腹部肥胖(OR=1.13);BPF检测(与未检测)与腹部肥胖患病率(OR=1.29)和BMI Z得分增加(β=0.10)相关;BPA和总双酚与一般肥胖、腹部肥胖或任何体质量结果均无统计学显著相关Urinary log-transformed concentrations of BPS were associated with increased risk of general obesity (OR=1.16) and ab-dominal obesity (OR=1.13); BPF detected (vs. no detected) was associated with increased prevalence of abdominal obesity (OR=1.29) and BMI Z score (β=0.10); neither BPA nor total bisphenols were associated with general obesity, abdominal o-besity or any weight outcome[79]美国United States产后Postnatal6~17BPA和BPF与一般和腹部肥胖的关系是正相关,BPS与肥胖无关,BPA的OR值为1.54,BPF的OR值为1.36;此外,BPA和BPF在男孩身上的相关性比女孩强BPA and BPF were positively associated with general and abdominal obesity, with OR of 1.54 for BPA and 1.36 for BPF, while BPS was not associated with obesity; in addition, BPA and BPF were more strongly correlated for boys[80]

注:BPA表示双酚A;BPF表示双酚F;BPS表示双酚S。

Note: BPA means bisphenol A; BPF means bisphenol F; BPS means bisphenol S.

表6 双酚类化合物对新生儿胎龄和出生体质量的影响

Table 6 Effect of bisphenols on gestational age and birth weight of newborns

续表6

样本Sample样本来源Source of sample国家Country年份Year时期Stage结论Conclusions参考文献References头发Hair母亲Maternal希腊Greece2018孕中期The second trimester of pregnancyBPA与出生体质量和早产无关,BPS与出生体质量升高有关BPA was not associated with birth weight and preterm birth, while BPS was positively associated with birth weight[37]尿液Urine母亲Maternal中国China2012—2014妊娠32~42周At 32~42 weeks gestationBPS与胎龄呈正相关,BPA与胎龄减少有关,二者与出生体质量无关BPS was positively associated with gestational age, and BPA was associated with reduced gesta-tional age; BPA and BPS were not associated with birth weight[90]尿液Urine母亲Maternal中国China2014—2015孕早、中和晚期Three trimesters of pregnancy母体孕期平均BPA浓度与妊娠期缩短和早产风险增加显著相关During pregnancy, maternal mean concentration of BPA was significantly associated with shorter gestational age and increased risk of preterm delivery[91]尿液Urine母亲Maternal美国United States2006—2008孕早期The first trimester of pregnancyBPS与早产正相关BPS was positively associated with preterm birth[92]尿液Urine母亲Maternal美国United States2006—2008孕早、中和晚期Three trimesters of pregnancyBPS与出生体质量不相关BPS was no associated with birth weight[93]尿液Urine母亲Maternal美国United States2015孕早、中和晚期Three trimesters of pregnancyBPA与出生体质量下降有关,BPS与出生体质量不相关BPA was negatively associated with birth weight, while no association between BPS and birth weight[94]血浆Plasma母亲Maternal中国China2015—2018BPA和BPF与出生体质量负相关,BPS与出生体质量无关BPA and BPF were negatively associated with birth weight, while no association between BPS and birth weight[95]尿液Urine母亲Maternal中国China2013—2015孕早、中和晚期Three trimesters of pregnancy在某些妊娠期间,尿中BPF和BPS浓度与出生体质量、出生长度或体质量指数显著降低相关During pregnant stages, urinary concentrations of BPF and BPS were negatively associated with birth weight, birth body length or body mass index[96]尿液Urine母亲Maternal美国United States2012—2015孕早期The first trimester of pregnancy BPS与较低出生体质量有关BPS was associated with lower birth weight[97]尿液Urine母亲Maternal美国United States2011—2017妊娠16~20, 20~24, 24~28周At 16~20, 20~24, 24~28 weeks gestation妊娠24~28周时,BPS与小于胎龄儿几率的增加有关,妊娠16~20周时与大于胎龄儿几率的增加有关BPS was associated with an increased risk of a small gestational age baby at 24~28 weeks ges-tation, and an increased risk of a larger gestational age baby at 16~20 weeks gestation[98]血浆Plasma脐带血Cord blood中国China2017—2018BPAF与早产和出生体质量显著正相关BPAF was positively associated with preterm delivery and birth weight[101]

注:BPA表示双酚A;BPF表示双酚F;BPS表示双酚S。

Note: BPA means bisphenol A; BPF means bisphenol F; BPS means bisphenol S.

[1] Micha owicz J. Bisphenol A - sources, toxicity and biotransformation [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2014, 37(2): 738-758

owicz J. Bisphenol A - sources, toxicity and biotransformation [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2014, 37(2): 738-758

[2] Reina-Pérez I, Olivas-Martínez A, Mustieles V, et al. Bisphenol F and bisphenol S promote lipid accumulation and adipogenesis in human adipose-derived stem cells [J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2021, 152: 112216

[3] Qiu W H, Shao H Y, Lei P H, et al. Immunotoxicity of bisphenol S and F are similar to that of bisphenol A during zebrafish early development [J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 194: 1-8

[4] Hill C E, Sapouckey S A, Suvorov A, et al. Developmental exposures to bisphenol S, a BPA replacement, alter estrogen-responsiveness of the female reproductive tract: A pilot study [J]. Cogent Medicine, 2017, 4(1): 1317690

[5] Yuan L L, Qian L, Qian Y, et al. Bisphenol F-induced neurotoxicity toward zebrafish embryos [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(24): 14638-14648

[6] Liu J C, Zhang L Y, Lu G H, et al. Occurrence, toxicity and ecological risk of bisphenol A analogues in aquatic environment - A review [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 208: 111481

[7] Chen D, Kannan K, Tan H L, et al. Bisphenol analogues other than BPA: Environmental occurrence, human exposure, and toxicity—A review [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(11): 5438-5453

[8] Chen Y C, Shu L, Qiu Z Q, et al. Exposure to the BPA-substitute bisphenol S causes unique alterations of germline function [J]. PLoS Genetics, 2016, 12(7): e1006223

[9] Zhu Q Q, Wang M, Jia J B, et al. Occurrence, distribution, and human exposure of several endocrine-disrupting chemicals in indoor dust: A nationwide study [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(18): 11333-11343

[10] Liao C Y, Liu F, Guo Y, et al. Occurrence of eight bisphenol analogues in indoor dust from the United States and several Asian countries: Implications for human exposure [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(16): 9138-9145

[11] Yang Y, Shi Y M, Chen D, et al. Bisphenol A and its analogues in paired urine and house dust from South China and implications for children’s exposure [J]. Chemosphere, 2022, 294: 133701

[12] Larsson K, Lindh C H, Jönsson B A, et al. Phthalates, non-phthalate plasticizers and bisphenols in Swedish preschool dust in relation to children’s exposure [J]. Environment International, 2017, 102: 114-124

[13] Zhang H F, Zhang Y P, Li J B, et al. Occurrence and exposure assessment of bisphenol analogues in source water and drinking water in China [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 655: 607-613

[14] Jin H B, Zhu L Y. Occurrence and partitioning of bisphenol analogues in water and sediment from Liaohe River Basin and Taihu Lake, China [J]. Water Research, 2016, 103: 343-351

[15] Zhu Q Q, Jia J B, Wang Y, et al. Spatial distribution of parabens, triclocarban, triclosan, bisphenols, and tetrabromobisphenol A and its alternatives in municipal sewage sludges in China [J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 679: 61-69

[16] Lee S, Liao C Y, Song G J, et al. Emission of bisphenol analogues including bisphenol A and bisphenol F from wastewater treatment plants in Korea [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 119: 1000-1006

[17] Yu X H, Xue J C, Yao H, et al. Occurrence and estrogenic potency of eight bisphenol analogs in sewage sludge from the US EPA targeted national sewage sludge survey [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2015, 299: 733-739

[18] Liao C Y, Liu F, Moon H B, et al. Bisphenol analogues in sediments from industrialized areas in the United States, Japan, and Korea: Spatial and temporal distributions [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2012, 46(21): 11558-11565

[19] Christensen K L Y, Lorber M, Koslitz S, et al. The contribution of diet to total bisphenol A body burden in humans: Results of a 48 hour fasting study [J]. Environment International, 2012, 50: 7-14

[20] Koch H M, Calafat A M. Human body burdens of chemicals used in plastic manufacture [J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences, 2009, 364(1526): 2063-2078

[21] Carwile J L, Ye X Y, Zhou X L, et al. Canned soup consumption and urinary bisphenol A: A randomized crossover trial [J]. JAMA, 2011, 306(20): 2218-2220

[22] Bae S, Hong Y C. Exposure to bisphenol A from drinking canned beverages increases blood pressure: Randomized crossover trial [J]. Hypertension, 2015, 65(2): 313-319

[23] Correia-Sá L, Kasper-Sonnenberg M, Schütze A, et al. Exposure assessment to bisphenol A (BPA) in Portuguese children by human biomonitoring [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017, 24(35): 27502-27514

[24] Rudel R A, Gray J M, Engel C L, et al. Food packaging and bisphenol A and bis(2-ethyhexyl) phthalate exposure: Findings from a dietary intervention [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2011, 119(7): 914-920

[25] Liao C Y, Kannan K. Concentrations and profiles of bisphenol A and other bisphenol analogues in foodstuffs from the United States and their implications for human exposure [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2013, 61(19): 4655-4662

[26] Liao C Y, Kannan K. A survey of bisphenol A and other bisphenol analogues in foodstuffs from nine cities in China [J]. Food Additives & Contaminants Part A, Chemistry, Analysis, Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment, 2014, 31(2): 319-329

[27] Grumetto L, Montesano D, Seccia S, et al. Determination of bisphenol A and bisphenol B residues in canned peeled tomatoes by reversed-phase liquid chromatography [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008, 56(22): 10633-10637

[28] Zoller O, Brüschweiler B J, Magnin R, et al. Natural occurrence of bisphenol F in mustard [J]. Food Additives & Contaminants Part A, Chemistry, Analysis, Control, Exposure & Risk Assessment, 2016, 33(1): 137-146

[29] Lee J, Choi K, Park J, et al. Bisphenol A distribution in serum, urine, placenta, breast milk, and umbilical cord serum in a birth panel of mother-neonate pairs [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 626: 1494-1501

[30] Zhang B, He Y, Zhu H K, et al. Concentrations of bisphenol A and its alternatives in paired maternal-fetal urine, serum and amniotic fluid from an e-waste dismantling area in China [J]. Environment International, 2020, 136: 105407

[31] Tschersich C, Murawski A, Schwedler G, et al. Bisphenol A and six other environmental phenols in urine of children and adolescents in Germany - human biomonitoring results of the German Environmental Survey 2014-2017 (GerES V) [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 763: 144615

[32] Liu Y H, Yan Z Y, Zhang Q, et al. Urinary levels, composition profile and cumulative risk of bisphenols in preschool-aged children from Nanjing suburb, China [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 172: 444-450

[33] Gys C, Ait Bamai Y, Araki A, et al. Biomonitoring and temporal trends of bisphenols exposure in Japanese school children [J]. Environmental Research, 2020, 191: 110172

[34] Li C, Zhao Y, Chen Y N, et al. The internal exposure of bisphenol analogues in South China adults and the associated health risks [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 795: 148796

[35] Gys C, Bastiaensen M, Bruckers L, et al. Determinants of exposure levels of bisphenols in Flemish adolescents [J]. Environmental Research, 2021, 193: 110567

[36] van der Meer T P, Artacho-Cordón F, Swaab D F, et al. Distribution of non-persistent endocrine disruptors in two different regions of the human brain [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017, 14(9): 1059

[37] Katsikantami I, Tzatzarakis M N, Karzi V, et al. Biomonitoring of bisphenols A and S and phthalate metabolites in hair from pregnant women in Crete [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 712: 135651

[38] Artacho-Cordón F, Arrebola J, Nielsen O, et al. Assumed non-persistent environmental chemicals in human adipose tissue; matrix stability and correlation with levels measured in urine and serum [J]. Environmental Research, 2017, 156: 120-127

[39] Heindel J J, Balbus J, Birnbaum L, et al. Developmental origins of health and disease: Integrating environmental influences [J]. Endocrinology, 2015, 156(10): 3416-3421

[40] Barker D J P. The developmental origins of chronic adult disease [J]. Acta Paediatrica Supplement, 2004, 93(446): 26-33

[41] Miller M D, Marty M A, Arcus A, et al. Differences between children and adults: Implications for risk assessment at California EPA [J]. International Journal of Toxicology, 2002, 21(5): 403-418

[42] Selevan S G, Kimmel C A, Mendola P. Identifying critical windows of exposure for children’s health [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2000, 108(Suppl.3): 451-455

[43] Braun J M. Early-life exposure to EDCs: Role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment [J]. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2017, 13(3): 161-173

[44] Henderson B E, Benton B, Jing J, et al. Risk factors for cancer of the testis in young men [J]. International Journal of Cancer, 1979, 23(5): 598-602

[45] Sharpe R M, Skakkebaek N E. Are oestrogens involved in falling sperm counts and disorders of the male reproductive tract? [J]. The Lancet, 1993, 341(8857): 1392-1396

[46] Kaimal A, Al Mansi M H, Dagher J B, et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenols affects pregnancy outcomes and offspring development in rats [J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 276: 130118

[47] Rubin B S, Murray M K, Damassa D A, et al. Perinatal exposure to low doses of bisphenol A affects body weight, patterns of estrous cyclicity, and plasma LH levels [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2001, 109(7): 675-680

[48] Yamasaki K, Noda S, Imatanaka N, et al. Comparative study of the uterotrophic potency of 14 chemicals in a uterotrophic assay and their receptor-binding affinity [J]. Toxicology Letters, 2004, 146(2): 111-120

[49] Stroheker T, Chagnon M C, Pinnert M F, et al. Estrogenic effects of food wrap packaging xenoestrogens and flavonoids in female Wistar rats: A comparative study [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2003, 17(4): 421-432

[50] Suades-González E, Gascon M, Guxens M, et al. Air pollution and neuropsychological development: A review of the latest evidence [J]. Endocrinology, 2015, 156(10): 3473-3482

[51] Kimura E, Matsuyoshi C, Miyazaki W, et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A impacts neuronal morphology in the hippocampal CA1 region in developing and aged mice [J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2016, 90(3): 691-700

[52] Wang H O, Chang L, Aguilar J S, et al. Bisphenol-A exposure induced neurotoxicity in glutamatergic neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells [J]. Environment International, 2019, 127: 324-332

[53] Zhong X Y, Li J S, Zhuang Z W, et al. Rapid effect of bisphenol A on glutamate-induced Ca2+ influx in hippocampal neurons of rats [J]. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2019, 485: 35-43

[54] Gao T T, Yin Z X, Wang M Y, et al. The effects of pubertal exposure to bisphenol-A on social behavior in male mice [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 244: 125494

[55] Wang J S, Jin S Z, Fu W S, et al. Pubertal exposure to bisphenol-A affects social recognition and arginine vasopressin in the brain of male mice [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 226: 112843

[56] Kinch C D, Ibhazehiebo K, Jeong J H, et al. Low-dose exposure to bisphenol A and replacement bisphenol S induces precocious hypothalamic neurogenesis in embryonic zebrafish [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(5): 1475-1480

[57] Zoeller R T, Rovet J. Timing of thyroid hormone action in the developing brain: Clinical observations and experimental findings [J]. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 2004, 16(10): 809-818

[58] Ahmed R G. Maternal bisphenol A alters fetal endocrine system: Thyroid adipokine dysfunction [J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 95: 168-174

[59] Lin C C, Chien C J, Tsai M S, et al. Prenatal phenolic compounds exposure and neurobehavioral development at 2 and 7 years of age [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 605-606: 801-810

[60] Braun J M, Muckle G, Arbuckle T, et al. Associations of prenatal urinary bisphenol A concentrations with child behaviors and cognitive abilities [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2017, 125(6): 067008

[61] Stein T P, Schluter M D, Steer R A, et al. Bisphenol A exposure in children with autism spectrum disorders [J]. Autism Research, 2015, 8(3): 272-283

[62] Qiu W H, Chen J S, Li Y J, et al. Oxidative stress and immune disturbance after long-term exposure to bisphenol A in juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio) [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2016, 130: 93-102

[63] Xu H, Yang M, Qiu W H, et al. The impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on oxidative stress and innate immune response in zebrafish embryos [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2013, 32(8): 1793-1799

[64] Dagher J B, Hahn-Townsend C K, Kaimal A, et al. Independent and combined effects of bisphenol A and diethylhexyl phthalate on gestational outcomes and offspring development in Sprague-Dawley rats [J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 263: 128307

[65] Gascon M, Casas M, Morales E, et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates and childhood respiratory tract infections and allergy [J]. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2015, 135(2): 370-378

[66] Buckley J P, Quirós-Alcalá L, Teitelbaum S L, et al. Associations of prenatal environmental phenol and phthalate biomarkers with respiratory and allergic diseases among children aged 6 and 7 years [J]. Environment International, 2018, 115: 79-88

[67] Kim K N, Kim J H, Kwon H J, et al. Bisphenol A exposure and asthma development in school-age children: A longitudinal study [J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(10): e111383

[68] Donohue K M, Miller R L, Perzanowski M S, et al. Prenatal and postnatal bisphenol A exposure and asthma development among inner-city children [J]. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2013, 131(3): 736-742

[69] Gillman M W. Early infancy as a critical period for development of obesity and related conditions [J]. Nestle Nutrition Workshop Series Paediatric Programme, 2010, 65: 13-20

[70] Ornoy A. Prenatal origin of obesity and their complications: Gestational diabetes, maternal overweight and the paradoxical effects of fetal growth restriction and macrosomia [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2011, 32(2): 205-212

[71] Héliès-Toussaint C, Peyre L, Costanzo C, et al. Is bisphenol S a safe substitute for bisphenol A in terms of metabolic function? An in vitro study [J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2014, 280(2): 224-235

[72] Meng Z Y, Wang D Z, Liu W, et al. Perinatal exposure to bisphenol S (BPS) promotes obesity development by interfering with lipid and glucose metabolism in male mouse offspring [J]. Environmental Research, 2019, 173: 189-198

[73] Wassenaar P N H, Trasande L, Legler J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of early-life exposure to bisphenol A and obesity-related outcomes in rodents [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2017, 125(10): 106001

[74] Li D K, Miao M H, Zhou Z J, et al. Urine bisphenol-A level in relation to obesity and overweight in school-age children [J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e65399

[75] Bhandari R, Xiao J, Shankar A. Urinary bisphenol A and obesity in US children [J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2013, 177(11): 1263-1270

[76] Wang H X, Zhou Y, Tang C X, et al. Association between bisphenol A exposure and body mass index in Chinese school children: A cross-sectional study [J]. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 2012, 11: 79

[77] Braun J M, Lanphear B P, Calafat A M, et al. Early-life bisphenol A exposure and child body mass index: A prospective cohort study [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2014, 122(11): 1239-1245

[78] Vafeiadi M, Roumeliotaki T, Myridakis A, et al. Association of early life exposure to bisphenol A with obesity and cardiometabolic traits in childhood [J]. Environmental Research, 2016, 146: 379-387

[79] Jacobson M H, Woodward M, Bao W, et al. Urinary bisphenols and obesity prevalence among US children and adolescents [J]. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 2019, 3(9): 1715-1726

[80] Liu B Y, Lehmler H J, Sun Y B, et al. Association of bisphenol A and its substitutes, bisphenol F and bisphenol S, with obesity in United States children and adolescents [J]. Diabetes & Metabolism Journal, 2019, 43(1): 59-75

[81] Grimaldi M, Boulahtouf A, Toporova L, et al. Functional profiling of bisphenols for nuclear receptors [J]. Toxicology, 2019, 420: 39-45

[82] Kelley A S, Banker M, Goodrich J M, et al. Early pregnancy exposure to endocrine disrupting chemical mixtures are associated with inflammatory changes in maternal and neonatal circulation [J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9: 5422

[83] Watkins D J, Ferguson K K, Anzalota del Toro L V, et al. Associations between urinary phenol and paraben concentrations and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation among pregnant women in Puerto Rico [J]. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2015, 218(2): 212-219

[84] Wei S Q, Fraser W, Luo Z C. Inflammatory cytokines and spontaneous preterm birth in asymptomatic women: A systematic review [J]. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2010, 116(2 Pt 1): 393-401

[85] Sam M. Myometrial progesterone responsiveness and the control of human parturition [J]. Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation, 2004, 11(4): 193-202

[86] Zakar T, Hertelendy F. Progesterone withdrawal: Key to parturition [J]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2007, 196(4): 289-296

[87] Qiu W H, Zhao Y L, Yang M, et al. Actions of bisphenol A and bisphenol S on the reproductive neuroendocrine system during early development in zebrafish [J]. Endocrinology, 2016, 157(2): 636-647

[88] Yang Q, Yang X H, Liu J N, et al. Effects of exposure to BPF on development and sexual differentiation during early life stages of zebrafish (Danio rerio) [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, 2018, 210: 44-56

[89] Hardin B D, Bond G P, Sikov M R, et al. Testing of selected workplace chemicals for teratogenic potential [J]. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 1981, 7(Suppl. 4): 66-75

[90] Wan Y J, Huo W Q, Xu S Q, et al. Relationship between maternal exposure to bisphenol S and pregnancy duration [J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 238: 717-724

[91] Huang S, Li J F, Xu S Q, et al. Bisphenol A and bisphenol S exposures during pregnancy and gestational age - A longitudinal study in China [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 237: 124426

[92] Aung M T, Ferguson K K, Cantonwine D E, et al. Preterm birth in relation to the bisphenol A replacement, bisphenol S, and other phenols and parabens [J]. Environmental Research, 2019, 169: 131-138

[93] Ferguson K K, Meeker J D, Cantonwine D E, et al. Environmental phenol associations with ultrasound and delivery measures of fetal growth [J]. Environment International, 2018, 112: 243-250

[94] Mustieles V, Williams P L, Fernandez M F, et al. Maternal and paternal preconception exposure to bisphenols and size at birth [J]. Human Reproduction, 2018, 33(8): 1528-1537

[95] Liang J, Liu S, Liu T, et al. Association of prenatal exposure to bisphenols and birth size in Zhuang ethnic newborns [J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 252: 126422

[96] Hu J, Zhao H Z, Braun J M, et al. Associations of trimester-specific exposure to bisphenols with size at birth: A Chinese prenatal cohort study [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2019, 127(10): 107001

[97] Goodrich J M, Ingle M E, Domino S E, et al. First trimester maternal exposures to endocrine disrupting chemicals and metals and fetal size in the Michigan Mother-Infant Pairs study [J]. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 2019, 10(4): 447-458

[98] Aker A M, Ferguson K K, Rosario Z Y, et al. The associations between prenatal exposure to triclocarban, phenols and parabens with gestational age and birth weight in northern Puerto Rico [J]. Environmental Research, 2019, 169: 41-51

[99] Berger K, Eskenazi B, Balmes J, et al. Prenatal high molecular weight phthalates and bisphenol A, and childhood respiratory and allergic outcomes [J]. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology: Official Publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 2019, 30(1): 36-46

[100] Vernet C, Pin I, Giorgis-Allemand L, et al. In utero exposure to select phenols and phthalates and respiratory health in five-year-old boys: A prospective study [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2017, 125(9): 097006

[101] Pan Y N, Deng M, Li J, et al. Occurrence and maternal transfer of multiple bisphenols, including an emerging derivative with unexpectedly high concentrations, in the human maternal-fetal-placental unit [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54(6): 3476-3486

[102] Teeguarden J G, Calafat A M, Ye X, et al. Twenty-four hour human urine and serum profiles of bisphenol A during high-dietary exposure [J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2011, 123(1): 48-57

[103] Jang Y, Choi Y J, Lim Y H, et al. Associations between thyroid hormone levels and urinary concentrations of bisphenol A, F, and S in 6-year-old children in Korea [J]. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 2021, 54(1): 37-45

[104] Pan X F, Wang L M, Pan A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China [J]. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2021, 9(6): 373-392

[105] 武阳丰, 马冠生, 胡永华,等. 中国居民的超重和肥胖流行现状[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2005, 39(5): 316-320

Wu Y F, Ma G S, Hu Y H, et al. The current prevalence status of body overweight and obesity in China: Data from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey [J]. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2005, 39(5): 316-320 (in Chinese)

[106] Grandin F C, Lacroix M Z, Gayrard V, et al. Is bisphenol S a safer alternative to bisphenol A in terms of potential fetal exposure? Placental transfer across the perfused human placenta [J]. Chemosphere, 2019, 221: 471-478

[107] Corbel T, Gayrard V, Puel S, et al. Bidirectional placental transfer of bisphenol A and its main metabolite, bisphenol A-Glucuronide, in the isolated perfused human placenta [J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2014, 47: 51-58