-

近几十年来,快速的城市化和工业化发展导致中国大气颗粒物污染恶化[1],尤其是细颗粒物(PM2.5)已成为国内城市的首要污染物[2]。PM2.5粒径小,吸附有害污染物能力强,组分复杂,容易进入到人体肺泡组织中,进而导致心血管系统、呼吸系统疾病[3]。多环芳烃(PAHs)是一类吸附在PM2.5上的有毒有机物,具有难降解、半挥发性的特点,可随着颗粒物迁移扩散造成持久性的大气污染。研究表明,肺癌与人体吸入的PAHs密切相关[4],孕妇长期暴露在PAHs污染环境下,会导致胎儿发育迟缓、畸形、早产等严重后果[5-6]。因此,美国环境保护局(US EPA)和欧盟已将16种PAHs列为优先控制污染物。

中国是世界上PAHs排放量较高的国家,2007年PAHs的排放量占全球排放量的21%[7]。目前,学者已对国内城市颗粒物中PAHs的季节变化、来源和健康风险进行了大量研究[8-10],但这些研究主要集中京津冀、长三角地区及省会城市,对级别较低高原城市的研究鲜有报道。遵义市地处云贵高原向湖南丘陵和四川盆地过渡的斜坡地带,是西南地区重要交通枢纽,也是贵州省工业分布主要区域,境内煤炭资源丰富。截至2019年末,遵义市常住人口630.2万人,机动车保有量133.3万辆[11]。随着城市化进程加快及新蒲新区建设,遵义市也面临着较严峻的大气污染问题。但目前对遵义市颗粒物的研究较少,对颗粒物中PAHs污染特征的研究尚未报道,而秋、冬季为遵义市大气颗粒物污染最严重的季节[12],掌握该阶段污染情况对全年大气污染的改善具有重要意义。因此,本研究通过采集遵义市秋、冬季(2020年10月~2021年1月)PM2.5样品,分析样品中PAHs的污染特征、来源及对人体健康风险,以期为遵义市大气污染控制和治理提供科学依据。

-

在遵义市设置3个采样点位,分别为汇川区大连路(大连路)、黄花岗区政府(忠庄,环境空气质量监测国控点)和新蒲新区大学城(新蒲)。大连路采样点位于遵义医科大学附属医院行政楼楼顶,周围有居民区、医院,交通流量较大;忠庄采样点以商业交通、居民区和学校为主,距离交通主干道海尔大道约50 m,靠近忠庄客运站和遵义南收费站;新蒲采样点位于遵义医科大学科研楼楼顶,周围分布着贵州航天职业技术学院、遵义医药高等专科学校和遵义师范学院等。其中,大连路、忠庄为典型的市区采样点,新蒲为郊区采样点,3个采样点周围均开阔,无建筑物遮挡,能在一定程度上代表遵义市大气污染的平均水平。

采样设备为TH-150A中流量采样器(武汉天虹),采样滤膜为whatman 90 mm石英滤膜,采样前在马弗炉中高温灼烧,以降低滤膜本底值。采样时间为2020年10月~2021年1月,其中2020年10月、11月代表秋季,2020年12月、2021年1月代表冬季,采样期内每个采样点每月采集12个样品,每个样品从当日9:00开始采集,至次日8:00结束,共收集PM2.5样品144个。采样期间的气象数据由遵义市生态环境局提供。

-

将采样滤膜剪碎后和硅藻土混匀,装入34 mL不锈钢萃取池,采用加速溶剂萃取仪(ASE350,Dionex)提取样品,提取剂为二氯甲烷,仪器参数:温度100 ℃,压力10.34 MPa,静态萃取5 min,循环2次,60 %溶剂冲洗,最后得到约80 mL提取液。将提取液经旋转蒸发仪浓缩到2 mL左右,再利用氮吹浓缩至1 mL以下,最后加入20 μL氘代多环芳烃内标溶液(Nap-D8、Ace-D10、Phe-D10、Chry-D12和Pery-D12),定容至1 mL待测。

采用气相色谱质谱联用仪(ISQ-TRACE 1310-AI 1310,Thermofisher)测定US EPA优控的16种PAHs,色谱柱为低流失毛细管柱(DB-5MS)。气相检测条件:进样口温度为300 ℃,不分流进样,升温程序:70 ℃保持2 min,然后以15 ℃/min升温至180 ℃,保持2 min,再以5 ℃/min升温至240 ℃,保持2 min,最后以3 ℃/min升温至315 ℃,保持2 min。质谱检测条件:传输线和离子源温度均为300 ℃,SIM模式扫描。使用内标法对PAHs进行定量分析。

-

PCA-MLR是一种采用受体模型来判断污染来源和计算源贡献的统计方法,利用SPSS软件提取主成分(PCA)后进行多元线性回归(MLR)计算污染源的贡献率,其基本方程见式(1)[13]:

式中:Y为遵义市样品中16种PAHs的总浓度;n为主成分提取的因子数;mi为第i个因子的标准化回归系数;Xi为第i个因子的得分变量;b为回归常数项。

-

PAHs具有较高的毒性和致癌性,其中,BaP对人体健康危害最大。通常采用US EPA推荐的BaP当量浓度(BaPeq)及终生致癌风险模型(ILCR)来评估PAHs对人体健康造成的危害。其中,BaP当量浓度法以BaP浓度为参考值计算出各PAHs 单体的BaPeq及总毒性当量浓度(TEQ),见式(2)[14]:

式中:TEQ为PAHs总毒性当量浓度;ci为PAHs单体质量浓度(ng/m3);TEFi为 PAHs单体的毒性等效因子。

PAHs通过呼吸暴露途径对人体产生致癌风险的计算,见式(3)[15]:

式中:CSF为BaP的致癌斜率因子,mg/(kg·d);c为PM2.5中PAHs毒性当量浓度,即为TEQ值;IR为呼吸速率,m3/d;EF为暴露频率,d/a;ED为持续暴露时间,d/a;BW为体重,kg;AT为终生致癌天数,d。不同年龄段人群暴露参数值,见表1。

-

实验过程中严格做好质量控制,所用试剂均为色谱纯,玻璃器皿在碱液中浸泡24 h后,先经自来水洗净后再用超纯水冲洗,并通过样品平行、空白膜加标和方法空白等方法来保证检测数据的可靠性。结果表明,16种PAHs标准曲线的线性相关系数较好,R2均大于0.995;空白膜加标回收率在76.5%~112.3%之间,满足检测要求;实际样品中PAHs的含量远高于方法检出限,浓度均经过空白校正。

-

遵义市3个采样点位样品中PAHs的浓度数据统计,见表2。

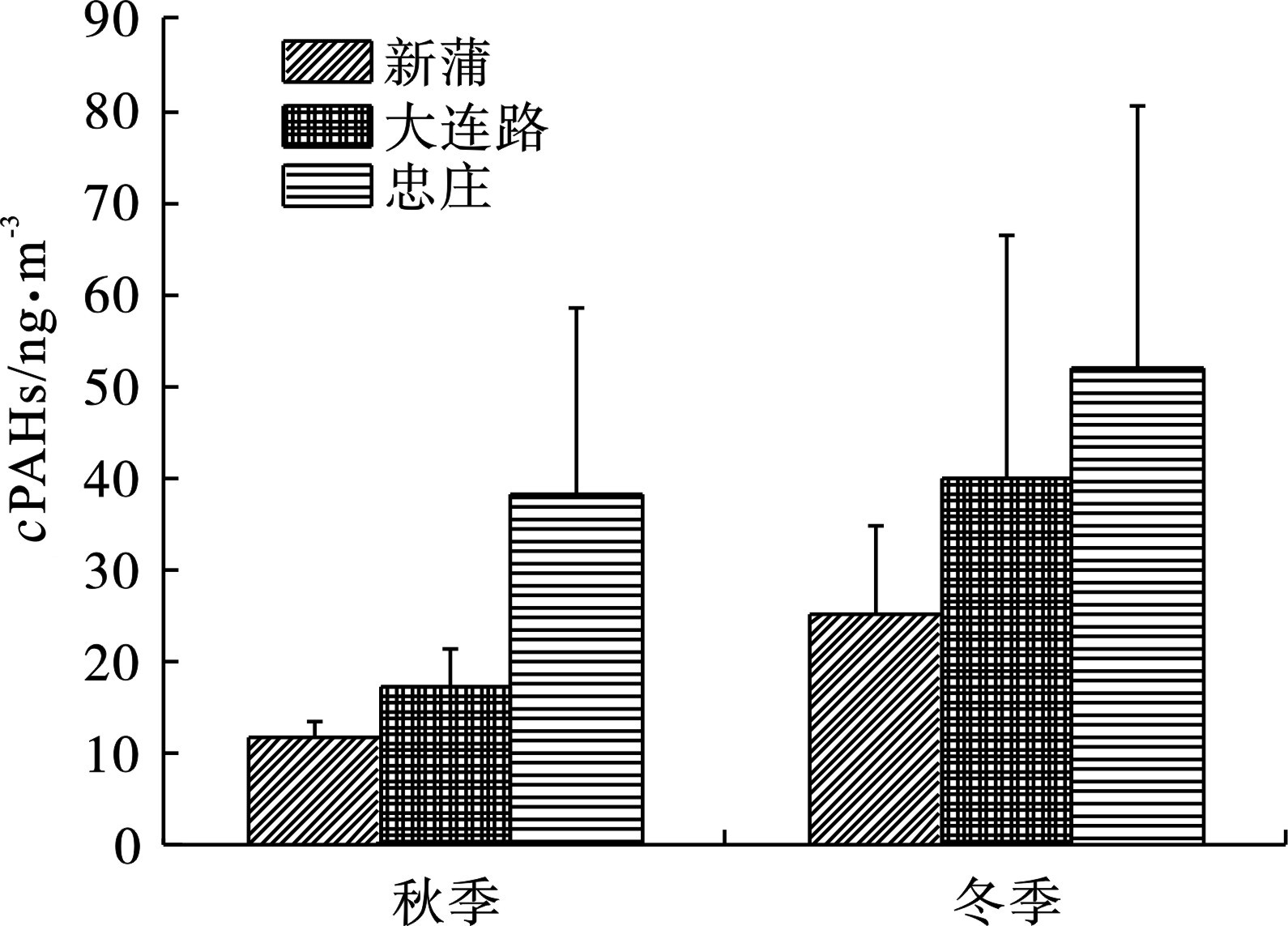

表2可知,研究期间遵义市PM2.5中16种PAHs浓度范围为9.68~108.80 ng/m3,均值为(30.53±22.63) ng/m3。不同采样点位PAHs浓度存在明显差异,忠庄最高(44.32±23.64 )ng/m3,大连路次之(28.86±22.20) ng/m3,新蒲最低(18.43±9.62) ng/m3。这可能是因为忠庄采样点位于中心城区,周围分布着商业区、交通主干道,来往人流量大,且采样点靠近忠庄客运站及遵义南收费站,出入城大型货车较多,导致该采样点PAHs污染较重;而新蒲采样点周围为学校,目前新蒲新区正在建设过程中,常住人口较少,加之采样期间受新冠疫情的影响,新区的基础设施建设进展较慢,导致人为污染较小,这应是新蒲采样点PAHs浓度较低的主要原因。与国内其他城市研究报道数据相比,遵义市PM2.5中PAHs的浓度远高于长春市 [16](1.33 ng/m3,2017~2018年)、香港特别行政区[17](4.59 ng/m3,2011~2012年)和上海市[18](6.90 ng/m3,2014~2015年)等,低于北京市(94.33 ng/m3,2015年)[2]、天津市(98.00 ng/m3,2015年)[2],表明遵义市PM2.5中PAHs污染处于中等水平。

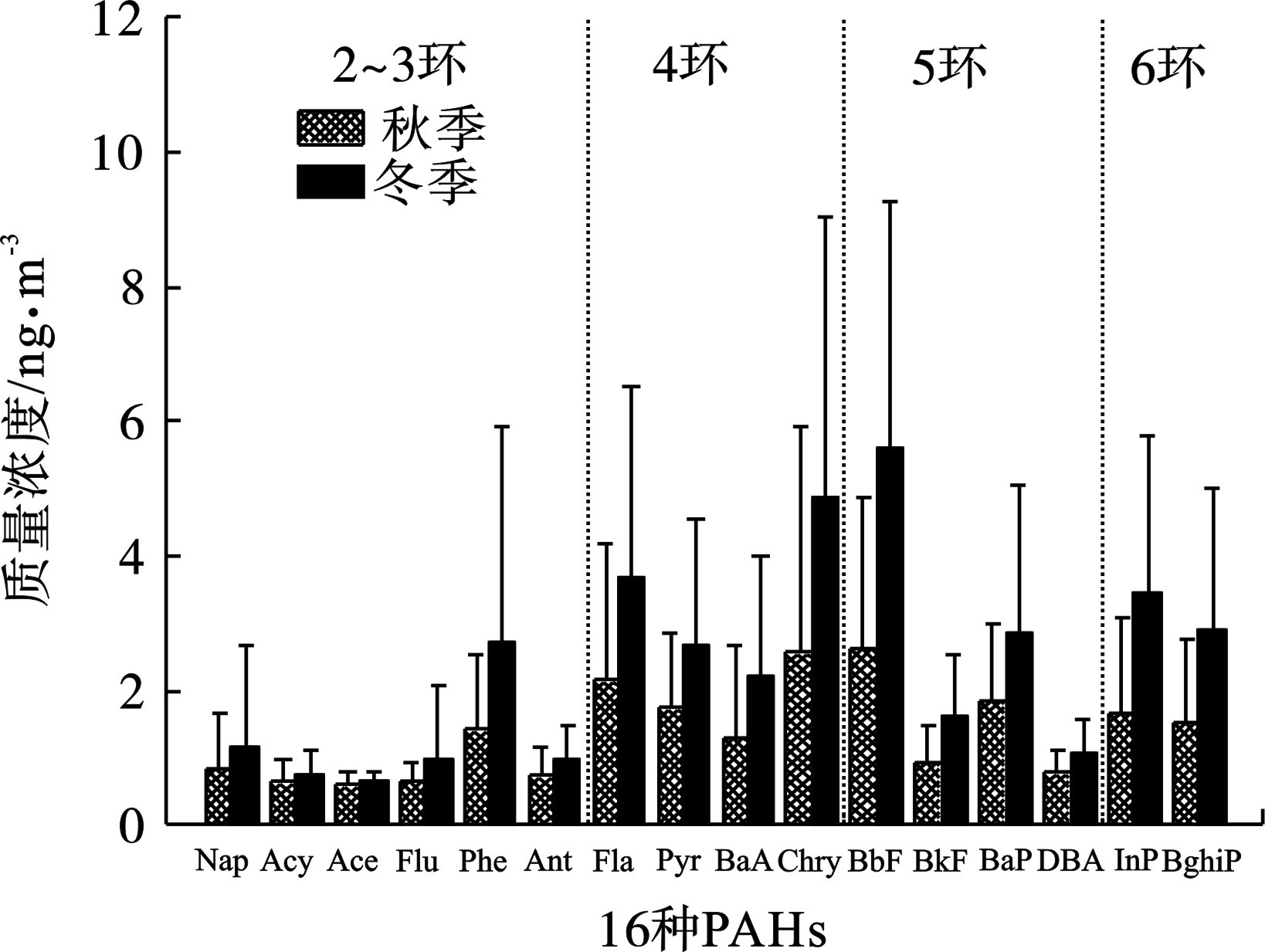

不同采样点PAHs浓度的季节变化,见图1。

3个采样点PAHs总平均质量浓度冬季高、秋季低,呈现明显的季节变化趋势。目前,遵义市能源结构仍以燃煤为主,冬季是采暖高峰期,燃煤用量显著增加,而燃煤排放是大气中PAHs的主要来源之一[19],这应是冬季PAHs浓度较高的原因之一。此外,气象条件也是影响颗粒物中PAHs浓度的重要因素[20],将采样期间PAHs的浓度与气象参数进行相关性分析,可知PAHs浓度与温度的Pearson系数为−0.608,在0.01水平(双侧)呈显著性负相关,即气温降低时,颗粒物中PAHs浓度升高;与风速、压强和相对湿度的Pearson系数分别为−0.202、0.212和−0.165,无显著相关性。研究期间遵义市秋、冬季的平均气温分别为15.3和4.0 ℃,由相关性分析可知,气温较低应是遵义市冬季颗粒物中PAHs较高的另一个因素。

-

为了解遵义市PM2.5中PAHs的组成特征,将其分为低环(2~3环,LMW)、中环(4环,MMW)和高环(5~6环,HMW)进行分析,秋季低环、中环和高环PAHs的质量浓度分别占16种PAHs总浓度的22%、35%和43%,冬季分别占19%、34%和47%,由此可知遵义市秋、冬季PAHs环数分布特征一致,高环>中环>低环,以高环、中环PAHs为主,低环PAHs含量最低。环数占比的不同一方面可能与遵义市污染源的排放有关,另一方面随着PAHs苯环数和分子量的增加,其在大气环境中固相分配系数增大,且秋、冬季气温低,大气层较稳定,这些因素共同导致中环、高环PAHs更易富集在颗粒物上[21],从而使得遵义市PM2.5中PAHs以中环、高环为主。

从不同PAHs单体来看,见图2。

图2可知,BbF的含量最高,冬季和秋季的平均浓度分别为5.60 和2.62 ng/m3,冬季含量是秋季的2.1倍。Chry和Fla的含量次之,冬季分别为4.88 和3.68 ng/m3,秋季分别为2.56和2.15 ng/m3,冬季含量明显大于秋季。研究表明,BbF、Chry和Fla是燃煤源的标志物[22-23],由此可知,燃煤是影响遵义市颗粒物中PAHs含量的重要因素。Ant和Acy的含量在秋、冬季都较低,Ant是自然成岩的特征物种,Acy来自石油源[24],表明研究区域自然源和石油源排放的PAHs较少。此外,环境空气质量标准(GB 3095—2012)中BaP的日均标准限值为2.5 ng/m3,而遵义市冬季PM2.5中BaP的平均浓度为2.84 ng/m3,超过标准限值,表明遵义市冬季PM2.5中PAHs的污染应引起重视。

-

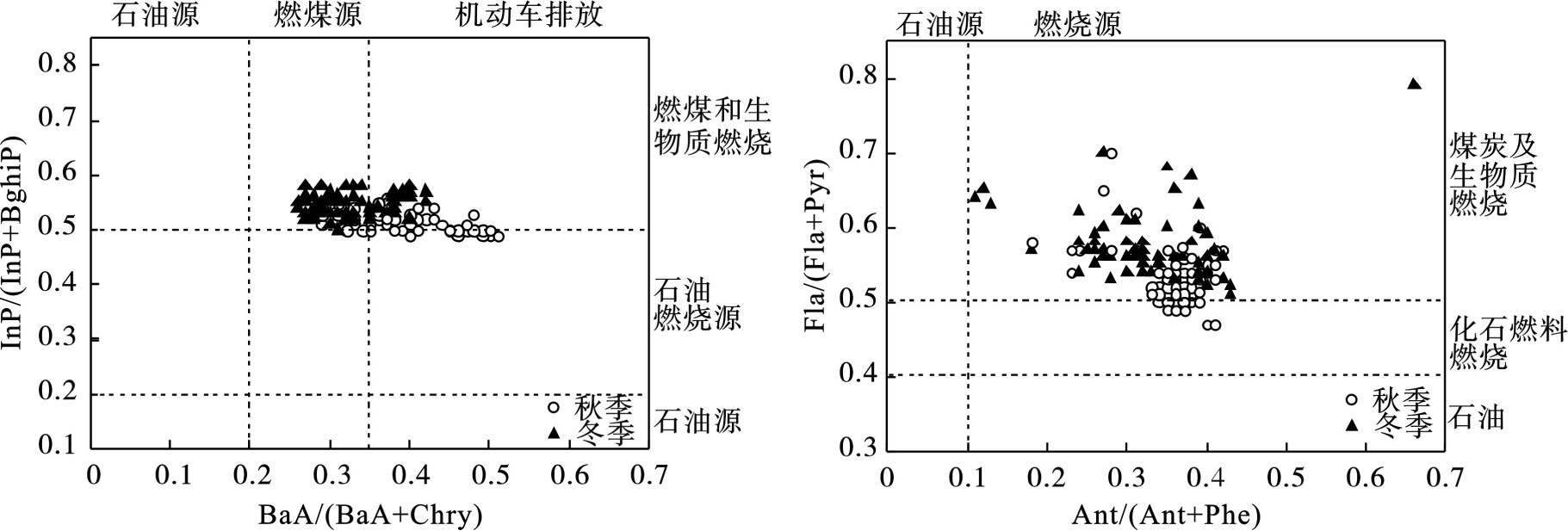

特征比值法是一种常用来判断颗粒物中PAHs来源的方法[25]。本研究利用Ant/(Ant+Phe)、Fla/(Fla+Pyr)、BaA/(BaA+Chry)及InP/(InP+BghiP)的比值来初步探讨遵义市PAHs的来源,见图3。

图3可知,遵义市秋、冬季PM2.5样品中PAHs的特征比值分布区域无显著差异,Ant/(Ant+Phe)的值>0.1,表明PAHs来源于燃烧源[26];Fla/(Fla+Pyr)和InP/(InP+BghiP)的值绝大部分>0.5,表明PAHs主要来源于煤炭及生物质燃烧[27];BaA/(BaA+Chry)的值在0.26~0.51之间,表明PAHs来源于燃煤与机动车排放[26]。此外,常用[4环/(5环+6环)]PAHs的比值来判断PAHs外来源和本地源的贡献[28],比值越小,说明本地源贡献越大,反之则以外来源为主。本研究中秋、冬季[4环/(5环+6环)]PAHs的平均比值分别为0.83和0.77,低于北京市沙尘暴天气期间的研究值5.9[29],表明PAHs的来源主要为本地源。综上可知,遵义市秋、冬季PM2.5中PAHs以本地源排放为主,燃煤、机动车尾气排放和生物质燃烧是其主要来源。

-

为进一步解析遵义市PM2.5中PAHs的来源和各源贡献率,采用多元统计法(PCA-MLR)对秋、冬季样品中16种PAHs进行分析,旋转后的因子载荷矩阵结果,见表3。

表3可知,在秋季,因子1中Nap、Ace、Flu、Phe、Fla、Chry和BbF载荷较高,其中Nap、Ace与生物质的燃烧排放密切相关[30],Flu、Phe、Fla、Chry和BbF是燃煤源的标志组分[23],因此因子1识别为生物质及煤炭燃烧混合源;因子2中BghiP的载荷最高、其次为InP和BkF,BghiP是汽油车尾气排放的示踪物[31],而InP和BkF是柴油燃烧排放的标志物[31],因此因子2识别为机动车尾气。冬季PAHs的来源与秋季相同,因子1和因子2分别识别为机动车尾气、煤及生物质燃烧。

将样品中PAHs的总含量标准化后作为因变量,以标准化主因子的分变量为自变量,利用SPSS19软件进行多元线性回归分析,可知秋、冬季决定系数R2分别为0.996和0.992,表明选用的回归模型拟合较好。然后根据秋季和冬季的线性回归方程,进一步求出各源的贡献率。分析结果表明,遵义市PAHs的主要污染源为燃煤和生物质燃烧混合源、机动车尾气,秋季贡献率分别为50.6%和49.4%,冬季分别为54.8%和45.2%。可知燃煤和生物质燃烧混合源排放对PAHs污染贡献最大,其次为机动车尾气。因此,改变以燃煤为主的能源结构,改善汽油、柴油品质,减少机动车尾气排放对遵义市大气污染防治具有重要意义。

-

根据公式(2)对采样期间各PAHs单体进行分析,从而得出各单体的毒性当量浓度(BaPeq)及总毒性当量浓度(TEQ),见表4。

表4可知,遵义市PAHs的BaPeq在0.000 4~3.448 73 ng/m3之间,BaP、DBA单体对TEQ值贡献最大。从不同采样点来看,忠庄TEQ值最大、大连路次之、新蒲最小,表明忠庄采样点的PAHs对当地暴露人群的健康危害更大。研究表明[32],TEQ值<1 ng/m3对人体健康危害不大,秋、冬季各采样点TEQ值均>1,且在冬季更高,表明遵义市PM2.5中PAHs对人体有潜在健康危害。

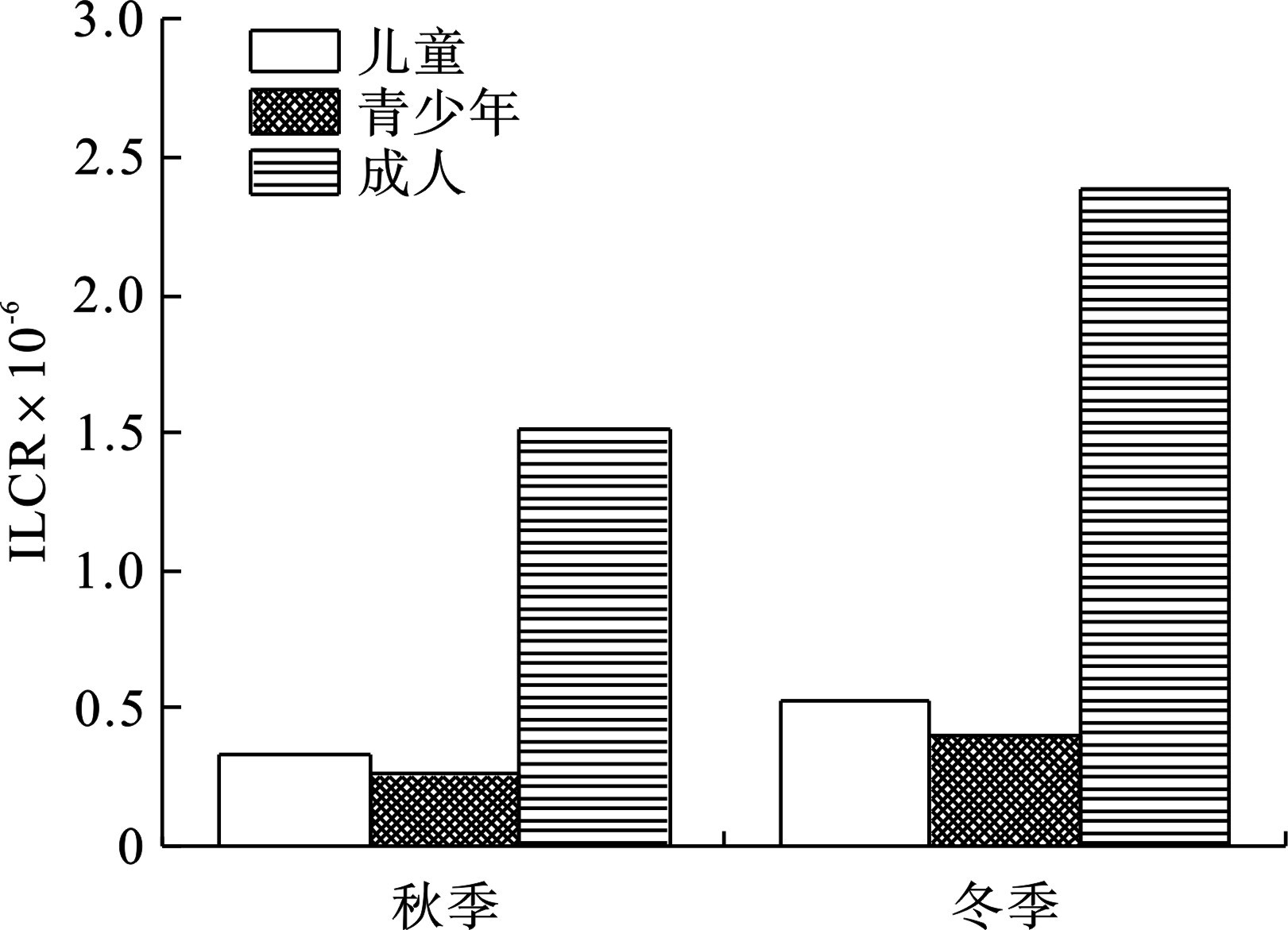

通过呼吸暴露途径对不同年龄段人群的致癌风险(ILCR)由公式(3)计算,见图4。

当ILCR值<10−6时,致癌风险可忽略;ILCR值在10−6~10−4之间,表明有潜在的致癌风险,ILCR值>10−4时,说明存在较高的致癌风险[33]。图4可知,遵义市不同年龄段人群的ILCR值存在差异,成年人的ILCR值显著高于儿童和青少年,这可能是因为成年人的户外活动较多,暴露时间较长。从不同季节来看,儿童、青少年的ILCR值<10−6,表明PAHs的致癌风险可以忽略,但成年人秋、冬季的ILCR值分别为1.51×10−6和2.39×10−6,高于10−6,表明有潜在的致癌风险,因此,遵义市PM2.5中PAHs的污染需要进一步控制。

-

(1)研究期间,遵义市PM2.5中16种PAHs浓度范围为9.68~108.80 ng/m3,平均值为(30.53±22.63) ng/m3,呈冬季高、秋季低的季节变化趋势。与国内其他城市相比,遵义市PM2.5中PAHs污染处于中等水平。

(2)遵义市秋、冬季PM2.5中PAHs环数分布特征一致,高环(HMW)>中环(MMW)>低环(LMW),以中环、高环PAHs为主。从不同PAHs单体来看,BbF的质量浓度最高、Chry、Fla其次,表明燃煤是影响遵义市颗粒物中PAHs含量的重要因素。

(3)特征比值法和PCA-MLR结果显示,遵义市PAHs主要来源于燃煤和生物质燃烧混合源、机动车尾气。其中,燃煤和生物质燃烧混合源对颗粒物中PAHs的贡献最大,秋季为50.6%,冬季为54.8%。

(4)BaP毒性当量浓度表明,遵义市冬季PAHs的健康风险高于秋季;ILCR分析表明,儿童、青少年的ILCR值都<10−6,表明致癌风险可以忽略,成年人的ILCR值高于10−6,表明有潜在的致癌风险。

遵义市秋冬季PM2.5中多环芳烃的污染特征、来源及健康风险评价

Characteristics, sources and health risk assessment of PAHs in PM2.5 during autumn and winter in Zunyi

-

摘要: 为探究遵义市秋、冬季PM2.5中多环芳烃(PAHs)的污染特征及来源,于2020年10月~2021年1月采集了遵义市大连路、忠庄和新蒲3个采样点位PM2.5样品,利用GC-MS对样品中16种优控PAHs进行分析,利用特征比值法和多元统计法(PCA-MLR)解析其来源,并采用BaP毒性当量浓度和终生致癌风险模型(ILCR)探讨了PAHs对人体的健康风险。结果表明,研究期间遵义市PM2.5中16种PAHs浓度范围为9.68~108.80 ng/m3,平均值为(30.53±22.63) ng/m3,呈冬季高、秋季低的季节变化趋势。秋、冬季PM2.5中PAHs环数分布特征一致,高环(5~6环)>中环(4环)>低环(2~3环),以中环、高环PAHs为主。PCA-MLR分析表明PAHs主要来自燃煤和生物质燃烧混合源、机动车尾气,其中,燃煤和生物质燃烧对颗粒物中PAHs的来源贡献最大,秋季为50.6%,冬季为54.8%。遵义市冬季PAHs总毒性当量浓度(TEQ)高于秋季,ILCR结果表明,成年人的ILCR值高于10-6,表明有潜在的致癌风险。Abstract: To investigate the pollution characteristics and sources of PAHs in PM2.5 in Zunyi during autumn and winter, PM2.5 samples were collected at Dalian Road, Zhongzhuang and Xinpu from October 2020 to January 2021. Then the concentrations of the 16 PAHs (US EPA priority) were analyzed by using gas chromatography mass spectrometer (GC-MS). Diagnostic ratios and principal component analysis-multiple linear regression (PCA-MLR) were performed for the 16 PAHs sources apportionment, and equivalent carcinogenic concentration of BaP and incremental lifetime cancer risks (ILCR) were applied to assess the health risk. The results showed that the concentrations of the 16 PAHs ranged from 9.68 to 108.80 ng/m3,with an average of 30.53±22.63 ng/m3 during the study period. The PAHs concentrations exhibited an obvious seasonal variation, with a higher level in winter than in autumn. The percentages of PAHs with different rings were in the following order, 5~6 ring PAHs >4 ring PAHs > 2~3 ring PAHs, 5~6 ring and 4 ring PAHs mainly occurred during autumn and winter. PCA-MLR indicated that PAHs were mainly derived from the emissions of coal combustion, biomass burning and motor vehicle. Coal combustion and biomass burning were the main pollution sources of PAHs in particulate matter, with 50.6% in autumn and 54.8% in winter. The TEQ in Zunyi was higher in winter than in autumn. The results from the risk model showed that the ILCR of adults exceeded 10−6, indicating the potential cancer risk of PAHs.

-

Key words:

- Zunyi /

- PAHs /

- PM2.5 /

- pollution characteristics /

- risk assessment

-

-

表 1 不同年龄段人群暴露参数值

Table 1. Exposure parameters value of different age groups

参数 儿童 青少年 成年人 CSF/d 3.14 3.14 3.14 IR/m3.d−1 12 15.7 15.7 EF/d.a−1 350 350 350 ED/a 6 6 42 BW/kg 31.1 53.3 62.9 AT/d 25 500 25 500 25 500 表 2 研究期间遵义市PM2.5中PAHs质量浓度

Table 2. Concentrations of PAHs in PM2.5 in Zunyi during the study period

ng·m−3 组分 新蒲(n=48) 大连路(n=48) 忠庄(n=48) 最小值 最大值 平均值 最小值 最大值 平均值 最小值 最大值 平均值 萘(Nap) 0.32 1.99 0.61±0.36 0.23 1.38 0.73±0.25 0.40 10.95 1.79±1.99 苊烯(Acy) 0.42 0.99 0.54±0.14 0.41 1.36 0.61±0.16 0.49 2.68 0.96±0.53 苊(Ace) 0.45 1.20 0.55±0.13 0.44 0.76 0.58±0.07 0.54 1.21 0.74±0.19 芴 (Flu) 0.49 1.21 0.62±0.16 0.48 1.31 0.69±0.21 0.56 7.68 1.22±1.36 菲(Phe) 0.75 3.31 1.25±0.67 0.75 3.85 1.51±0.79 0.92 30.79 3.67±4.24 蒽(Ant) 0.43 1.49 0.67±0.27 0.42 1.42 0.75±0.25 0.62 3.84 1.21±0.68 荧蒽(Fla) 0.81 4.72 1.94±1.05 1.02 7.36 2.35±1.57 1.21 16.95 4.65±3.75 芘(Pyr) 0.78 3.60 1.50±0.69 0.88 6.11 1.93±1.21 0.96 10.51 3.29±2.16 苯并(a)蒽(BaA) 0.50 2.33 0.92±0.51 0.48 8.93 1.77±1.97 0.77 7.79 2.64±1.65 屈(Chry) 0.51 6.59 1.71±1.53 0.47 18.77 3.56±4.28 1.26 16.58 6.13±4.13 苯并(b)荧(BbF) 0.67 7.64 2.36±1.83 0.69 17.51 4.42±3.9 1.42 14.57 5.63±3.22 苯并(k)荧(BkF) 0.47 2.06 0.84±0.41 0.48 4.92 1.33±0.99 0.80 3.94 1.66±0.78 苯并(a)芘(BaP) 0.93 3.49 1.47±0.60 1.08 10.91 2.66±2.23 1.06 8.51 2.97±1.81 茚并(1,2,3-cd)芘 (InP) 0.50 4.95 1.50±1.08 0.50 11.36 2.70±2.44 1.14 9.23 3.52±2.04 二苯并(a,h)蒽(DBA) 0.49 1.36 0.70±0.22 0.49 2.88 0.90±0.48 0.63 2.57 1.17±0.48 苯并(ghi)苝 (BghiP) 0.50 4.07 1.26±0.82 0.53 10.16 2.35±2.15 1.11 8.46 3.09±1.87 ∑ 16PAHs 10.01 47.33 18.43±9.62 9.68 104.19 28.86±22.20 15.73 108.80 44.32±23.64 表 3 遵义市秋、冬季PM2.5中PAHs的PCA-MLR分析

Table 3. PCA-MLR for PAHs in PM2.5 in Zunyi during autumn and winter

化学物质 秋季 冬季 因子1 因子2 因子1 因子2 Nap 0.961 0.195 −0.665 0.981 Acy 0.544 0.307 0.183 0.605 Ace 0.947 0.219 0.21 0.658 Flu 0.929 0.343 −0.033 0.969 Phe 0.884 0.412 −0.035 0.965 Ant 0.360 0.208 0.169 0.456 Fla 0.800 0.447 0.457 0.829 Pyr 0.811 0.534 0.617 0.690 BaA 0.518 0.827 0.961 0.167 Chry 0.807 0.564 0.388 0.903 BbF 0.849 0.475 0.506 0.901 BkF 0.299 0.948 0.990 0.122 BaP 0.453 0.869 0.879 0.212 InP 0.286 0.949 0.993 0.060 DBA 0.538 0.820 0.973 0.116 BghiP 0.245 0.962 0.991 0.090 贡献方差 78.400 17.400 60.600 31.700 贡献率/% 50.600 49.400 45.200 54.800 来源 煤炭、生

物质燃烧机动车

尾气机动车

尾气煤炭、生

物质燃烧表 4 遵义市PM2.5中PAHs的毒性当量

Table 4. TEQ of PAHs in PM2.5 in Zunyi

ng·m−3 组分 TEF[15] 秋季 冬季 新蒲 大连 忠庄 新蒲 大连路 忠庄 Nap 0.001 0.000 4 0.000 6 0.001 5 0.000 8 0.000 8 0.002 1 Acy 0.001 0.000 5 0.000 5 0.000 9 0.000 6 0.000 7 0.001 0 Ace 0.001 0.000 5 0.000 5 0.000 8 0.000 6 0.000 6 0.000 7 Flu 0.001 0.000 5 0.000 6 0.000 9 0.000 7 0.000 8 0.001 6 Phe 0.001 0.000 8 0.001 1 0.002 4 0.001 7 0.001 9 0.005 2 Ant 0.010 0.004 9 0.006 1 0.011 2 0.008 5 0.009 0 0.013 1 Fla 0.001 0.001 3 0.001 5 0.003 7 0.002 6 0.003 1 0.005 8 Pyr 0.001 0.001 2 0.001 4 0.002 7 0.001 8 0.002 4 0.004 0 BaA 0.100 0.056 4 0.079 3 0.262 3 0.128 0 0.271 0 0.266 1 Chry 0.010 0.007 1 0.013 3 0.058 3 0.027 0 0.057 1 0.065 0 BbF 0.100 0.102 5 0.220 8 0.474 2 0.369 2 0.655 0 0.670 2 BkF 0.100 0.054 9 0.081 7 0.146 4 0.113 8 0.183 1 0.190 6 BaP 1.000 1.209 9 1.838 0 2.605 4 1.724 4 3.448 7 3.418 5 InP 0.100 0.070 9 0.131 5 0.305 0 0.228 6 0.402 5 0.408 8 DBA 1.000 0.552 2 0.694 4 1.086 0 0.853 1 1.096 6 1.279 3 BghiP 0.010 0.007 0 0.012 5 0.026 6 0.018 3 0.034 0 0.036 1 TEQ − 2.070 7 3.083 9 4.988 2 3.479 7 6.167 3 6.368 0 注:TEF为 PAHs单体的毒性等效因子。 -

[1] ZHANG X, ZHAO X, JI G, et al. Seasonal variations and source apportionment of water-soluble inorganic ions in PM2.5 in Nanjing, a megacity in southeastern China[J]. Journal of Atmospheric Chemistry, 2019, 76(1): 73 − 88. doi: 10.1007/s10874-019-09388-z [2] LI Z Y, WANG Y T, LI Z X, et al. Levels and sources of PM2.5–associated PAHs during and after the wheat harvest in a central rural area of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) region[J]. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 2020, 20(5): 1070 − 1082. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2020.03.0083 [3] ZHANG X H, LU Y, WANG Q G, et al. A high-resolution inventory of air pollutant emissions from crop residue burning in China[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2019, 213: 207 − 214. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.06.009 [4] ZHOU M, WANG H, ZHU J, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013: A systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013[J]. Lancet, 2016, 387(10015): 251 − 272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6 [5] PETRY T, SCHMID P, SCHLATTER C. The use of toxic equivalency factors in assessing occupational and environmental health risk associated with exposure to airborne mixtures of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)[J]. Chemosphere, 1996, 32(4): 639 − 648. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00348-7 [6] BOLDEN A L, ROCHESTER J R, SCHULTZ K, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and female reproductive health: A scoping review[J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2017, 73: 61 − 74. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.07.012 [7] SHEN H, HUANG Y, WANG R, et al. Global atmospheric emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from 1960 to 2008 and future predictions[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(12): 6415 − 6424. [8] YAN D H, WU S H, ZHOU S L, et al. Characteristics, sources and health risk assessment of airborne particulate PAHs in Chinese cities: A review[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 248: 804 − 814. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.02.068 [9] LIU Y, YU Y, LIU M, et al. Characterization and source identification of PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in different seasons from Shanghai, China[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 644(10): 725 − 735. [10] ZHANG T C, CHEN Y F, XU X H. Health risk assessment of PM2.5-bound components in Beijing, China during 2013-2015[J]. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 2020, 20: 1938 − 1949. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2020.03.0108 [11] 贵州省统计局, 国家统计局贵州调查总队. 贵州统计年鉴2020[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 2020. [12] 张勇, 陈荣祥, 陈卓, 等. 遵义市PM2.5中水溶性离子的污染特征及来源解析[J]. 地球与环境, 2020, 48(5): 552 − 557. [13] LIU X H, LIU Y, LU S Y, et al. Occurrence of typical antibiotics and source analysis based on PCA-MLR model in the East Dongting Lake, China[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2018, 163: 145 − 152. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.07.067 [14] JUNG K H, YAN B Z, CHILLRUD S N, et al. Assessment of benzo(a) pyrene-equivalent carcinogenicity and mutagenicity of residential indoor versus outdoor polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposing young children in New York city[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2010, 7(5): 1889 − 1900. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7051889 [15] 李宽, 周家斌, 袁畅, 等. 武汉市大气PM2.5中多环芳烃的分布特征及来源[J]. 环境科学研究, 2018, 31(4): 648 − 656. [16] 李 娜, 魏 鑫, 周宇峰, 等. 长春市大气环境PM2.5中多环芳烃的来源解析及健康风险评价[J]. 科学技术与工程, 2021, 21(1): 410 − 416. [17] MA Y, CHENG Y, QIU X, et al. A quantitative assessment of source contributions to fine particulate matter (PM2.5)-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their nitrated and hydroxylated derivatives in Hong Kong[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 219: 742 − 749. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.07.034 [18] WANG Q, LIU M, YU Y P, et al. Characterization and source apportionment of PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from Shanghai City, China[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 218: 118 − 128. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.037 [19] TIAN F L, CHEN J W, QIAO X L, et al. Sources and seasonal variation of atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Dalian, China: Factor analysis with non-negative constraints combined with local source fingerprints[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2009, 43(17): 2747 − 2753. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.02.037 [20] HE J B, FAN S X, MENG Q Z, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) associated with fine particulate matters in Nanjing, China: distributions, sources and meteorological influences[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 89: 207 − 215. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.02.042 [21] 齐文静, 张瑞芹, 姜楠, 等. 洛阳市秋、冬季 PM2.5中多环芳烃的污染特征、来源解析及健康风险评价[J]. 环境科学, 2021, 42(2): 595 − 603. [22] LI J W, LI X D, LI M, et al. Influence of air pollution control devices on the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon distribution in flue gas from an ultralow-emission coal-fired power plant[J]. Energy&Fuels, 2016, 30(11): 9572 − 9579. [23] BRAGATO M, JOSHI K, CARLSON J B, et al. Combustion of coal, bagasse and blends thereof: part Ⅱ: speciation of PAH emissions[J]. Fuel, 2012, 96: 51 − 58. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2011.11.069 [24] GAO Y, JI H B. Characteristics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons components in fine particle during heavy polluting phase of each season in urban Beijing[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 212: 346 − 357. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.08.079 [25] REN Y Q, ZHOU B H, TAO J, et al. Composition and size distribution of airborne particulate PAHs and oxygenated PAHs in two Chinese megacities[J]. Atmospheric Research, 2017, 183: 322 − 330. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosres.2016.09.015 [26] MANCILL Y, MENDOZA A, FRASER M P, et al. Organic composition and source apportionment of fine aerosol at Monterrey, Mexico, based on organic markers[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 2016, 16(2): 953 − 970. doi: 10.5194/acp-16-953-2016 [27] DE L TORRE-ROCHE R J, LEE W Y, CAMPOS-DIAZ S I. Soil-borne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in El Paso, Texas: analysis of a potential problem in the United States/Mexico border region[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009, 163(2-3): 946 − 958. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.07.089 [28] MVILLAR M, LERTXUND M A, MARTINEZ L, et al. Air polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) associated with PM2.5 in a North Cantabric coast urban environment[J]. Chemosphere, 2014, 99: 233 − 238. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.11.006 [29] RAJPUT P, SARIN M M, SHARMA D, et al. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and isomer ratios as tracers of biomass burning emissions in northern India[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 2014, 21(8): 5724 − 5729. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2496-5 [30] BOUROTTE C, FORTI M, TANIGUCHI S, et al. A wintertime study of PAHs in fine and coarse aerosols in Sao Paulo City, Brazil[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2005, 39(21): 3799 − 3811. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.02.054 [31] KHAN M F, LATIF M T, LIM C H, et al. Seasonal effect and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM2.5[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2015, 106: 178 − 190. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.01.077 [32] 宋光卫, 胡健, 崔猛, 等. 北京市奥林匹克公园PM2.5中多环芳烃在采暖季和非采暖季的特征、来源及健康风险评估[J]. 生态学杂志, 2019, 38(11): 3400 − 3407. [33] MA Y, LIU A, EGODAWATTA P, et al. Quantitative assessment of human health risk posed by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban road dust[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 575: 895 − 904. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.148 -

下载:

下载: